This website is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Take a look at a selection of our recent media coverage:

12th October 2023

Non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) causes more global deaths than melanoma, despite its lower severity, and dark skin phenotypes were found to be at risk, according to research presented at the recent European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress 2023.

Using data from the World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer data, the researchers looked at global skin cancer epidemiology, focusing particularly on population risk profiles and impact of dermatologist density on incidence and mortality.

They found that in 2020, NMSC was responsible for 63,731 deaths compared to the 57,043 deaths recorded from melanoma during the same year. However, as NMSC is often underreported in cancer registries, they noted that these figures may be underestimated.

Commenting on the top-line results, lead author of the study, Professor Thierry Passeron, professor and chair of dermatology in the University Hospital of Nice, said: ‘Although NMSC is less likely to be fatal than melanoma skin cancer, its prevalence is strikingly higher. In 2020, NMSC accounted for 78% of all skin cancer cases, resulting in over 63,700 deaths. In contrast, melanoma caused an estimated 57,000 fatalities in the same year. The significantly higher incidence of NMSC has, therefore, led to a more substantial overall impact.‘

Mapping of the data also identified a higher skin cancer incidence in fair-skinned and elderly populations from the USA, Germany, UK, France, Australia and Italy. In Africa, 11,281 skin cancer deaths were registered, demonstrating that even countries with a higher proportion of dark phenotypes are at risk.

Overall, individuals who were at a higher risk of melanoma were the elderly (relative risk, RR = 8.5), organ transplant recipients (RR = 8.0) and those with xeroderma pigmentosum (RR = 2,000). Those who worked outside were also deemed to have greater risk of NMSC than melanoma.

Commenting further on these findings, Professor Passeron said: ‘We have to get the message out that not only melanoma can be fatal, but NMSC also. It‘s crucial to note that individuals with melanin-rich skin are also at risk and are dying from skin cancer. There is a need to implement effective strategies to reduce the fatalities associated with all kinds of skin cancers.‘

When it came to dermatologist density, there was no evidence to suggest having more dermatologists per capita could reduce mortality rates. The researchers found that countries with fewer dermatologists, such as Australia, the UK and Canada, exhibited low mortality-to-incidence ratios.

Professor Passeron continued: ‘We therefore need to explore what strategies these countries are employing to reduce the impact of skin cancer in further depth. The involvement of other healthcare practitioners, such as GPs, in the identification and management of this disease may partly explain their success. There remains huge opportunity worldwide to elevate the role of GPs and other healthcare professionals in this process and train them to recognise suspicious lesions early.

‘In alignment with this, there is an ongoing need to develop awareness campaigns that educate the general public about the risks of sun exposure and other relevant risk factors. These campaigns should be tailored to at-risk populations, including those with fair skin, outdoor workers, the elderly and individuals who are immunosuppressed. Importantly, these efforts should also extend to populations that may not typically be considered at high risk, such as darker-skinned populations.’

NMSC has become a significant public health threat with a 2022 study showing that the incidence rate increased from 54.08 per 100,000 population in 1990 to 79.10 per 100,000 in 2019.

24th August 2023

Patients with greater levels of self-reported pain one year after a myocardial infarction (MI) have a significantly higher risk of subsequent mortality, according to a new study.

It is recognised that in patients with symptomatic chest pain, markers such as coronary artery calcium score and cystatin C levels are linked to a higher risk of all-cause mortality.

In addition, self-reported chronic pain is also linked to a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes including MI and stroke, independently of established cardiovascular risk factors. The extent to which any post-MI pain impacts on subsequent mortality is to be determined.

To this end, in the recent study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, Swedish researchers aimed to examine various levels of pain severity one year after an MI as a potential risk for all-cause mortality.

The team collated data from patients who had a registered MI event between 2004 and 2013 with measurements of potential cardiovascular risk indicators at hospital discharge from the Swedish quality register SWEDEHEART database.

Self-reported levels of experienced pain according to EuroQol-5 dimension instrument were recorded in secondary prevention clinics one year after their hospital discharge. The researchers set the primary outcome as all‐cause mortality.

A total of 18,376 patients with complete data were included in the analysis, and all-cause mortality data were collected up to 8.5 years (median 3.4 years) after the one-year visit. There were 1,067 recorded deaths.

Self-reported moderate pain and extreme pain were reported by 38.2% and 4.5% of included patients, respectively.

In fully adjusted models, the mortality risk among those with self-reported moderate severity pain was 35% higher than for those not reporting pain (hazard ratio, HR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.18 – 1.55, p < 0.0001).

But in those reporting severe pain, the risk was more than doubled (HR = 2.06, 95% CI 1.63 – 2.60, p < 0.0001). In fact, pain was a stronger mortality predictor than smoking.

The researchers suggested that clinicians managing post-MI patients should recognise the need to consider those with self-reported pain as a prognostic factor, which is comparable to persistent smoking, and to address this when tailoring secondary prevention treatments.

16th August 2023

The use of beta-blockers is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and a trend for a higher mortality risk among patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), according to the findings from a recent study.

Researchers from University College London School of Pharmacy found that the use of beta-blocker drugs in patients with OSA increases the five-year risk of mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

In the absence of real-world evidence, the study, published in The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, investigated the impact of beta-blocker use on all-cause mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with OSA.

For the purposes of their analysis, the researchers turned to IQVIA Medical Research Data – a nationwide database of primary care records in the UK that contains around 6% of the total UK population in 2015. The database includes demographic and lifestyle information such as smoking and alcohol consumption, medical diagnoses and procedures, together with prescribing information.

Included patients were adults aged over 18 who had a diagnosis of OSA in their medical records. The team then compared the treatment strategies of initiating oral beta-blockers versus not starting a beta-blocker in these patients.

The outcomes of interest were all-cause mortality or a diagnosis of CVD, defined as a composite event of angina, myocardial infarction, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, heart failure or atrial fibrillation.

A total of 37,581 patients met the eligibility criteria and were followed for a median of 4.1 years.

The five-year absolute risk of all-cause mortality and CVD outcomes were 4.9% and 13.0% among beta-blocker users, compared to 4.0% and 9.4% among non-beta-blocker users, respectively.

Commenting on these findings, study lead Dr Kenneth Man said: ‘Our study underscores the urgent need for further investigation into the relationship between beta-blockers and health outcomes in OSA patients.

‘Our hope is that this information will help medical professionals make more informed decisions when treating patients with OSA.‘

This extensive study is one of the few exploring the real-world implications of medical treatment in OSA patients. It emphasises the importance of careful and continued monitoring of these patients and encourages further investigation in this field.

Further studies are anticipated to confirm these findings and delve deeper into understanding the association between beta-blocker usage and patient outcomes. Until such studies are conducted, the medical community is urged to consider the potential risks highlighted by this research when treating patients with OSA.

19th July 2023

Repeating liver stiffness measurements (LSM) allows for an individual and updated risk assessment for decompensation and mortality in patients with advanced chronic liver disease (CLD), a study has found.

LSM provide an opportunity for clinicians to non-invasively monitor liver disease progression and even regression. But is there a prognostic value in measurement of liver stiffness dynamics over time for liver-related events and death in patients with CLD?

This was the question posed in a recent retrospective study, published in the journal Gastroenterology by a team of researchers from the Department of Internal Medicine III at the Medical University of Vienna and University Hospital Vienna in Austria. They showed that the dynamics of LSM are directly linked to either an increased or decreased risk for hepatic decompensation in compensated and decompensated advanced CLD.

Researchers focused on patients with CLD undergoing more than two reliable LSM at least 180 days apart. For the purposes of the analysis, patients were categorised as having non-advanced CDL (nonACLD), compensated advanced CLD (cACLD) and decompensated advanced CLD (dACLD).

The primary objective to assess the association of longitudinal changes in LSM with clinical events of hepatic decompensation in nonACLD and cACLD patients. A range of secondary objectives included a comparison of LSM dynamics between different disease severity groups and an exploratory analysis of the impact of dynamics of LSM on liver-related mortality in dACLD.

A total of 2,508 patients with 8,561 reliable LSM (a median of three per patient) were included in the analysis. This comprised 65.7% with non-ACLD, 30.2% with cACLD and 4.1% with dACLD. In addition, 83 patients with cACLD developed hepatic decompensation after a median follow-up of 71 months.

The researchers found that a 20% increase in LSM at any time was associated with an increased risk for hepatic decompensation (Hazard ratio, HR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.41 – 1.79, p < 0.001) as well as hepatic-related mortality (HR = 1.45, 95% CI 1.28 – 1.68, p < 0.001) in cACLD patients.

In addition, LSM dynamics yielded a high accuracy to predict hepatic decompensation in the following 12 months (area under the curve, AUC = 0.933). This performance was numerically superior to dynamics in FIB-4 (AUC = 0.873), MELD (AUC = 0.835) and single time-point LSM.

Any LSM decrease to less than 20 kPa identified cACLD patients with a substantially lower risk of hepatic decompensation (HR = 0.13, 95% CI 0.07 – 0.24).

Commenting on these findings, the study’s principal investigator Thomas Reiberger said: ‘An understanding of the individual patient’s personal risk profile means that it is possible to initiate optimised, personalised treatment.‘

Indeed, taken together, the findings of the study reveal how regular measurements of liver stiffness indicate a personalised patient risk profile, which enables the initiation of individualised treatment strategies.

4th July 2023

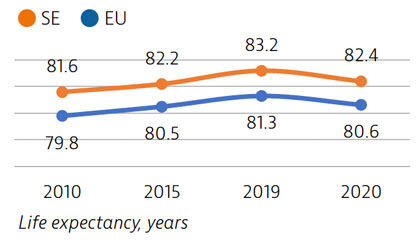

Life expectancy in Sweden is among the highest in the EU, although it declined by nearly one year in 2020 as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. The healthcare system generally performs well in providing good access to high-quality care.

However, challenges persist in providing equal access to care for the population living in different regions, ensuring timely access to care, achieving greater care coordination for people with chronic diseases and improving the quality of long-term care.

Life expectancy at birth was 82.4 years in 2020 – almost two years above the EU average – but it fell by almost one year in 2020 because of the high number of deaths from Covid-19. More than two thirds of Covid-19 deaths were among people aged 80 and over.

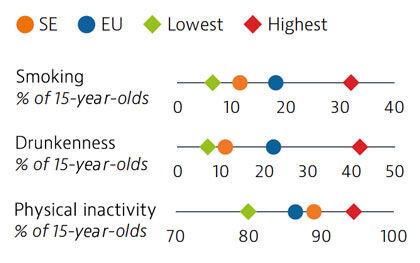

Smoking rates among adults in Sweden are among the lowest in EU countries, but use of other tobacco products such as snuff is common. Overall alcohol consumption per adult has decreased over the past decade and is much lower than the EU average. Adolescents in Sweden also report low rates of smoking and excessive alcohol intake, but high rates of physical inactivity.

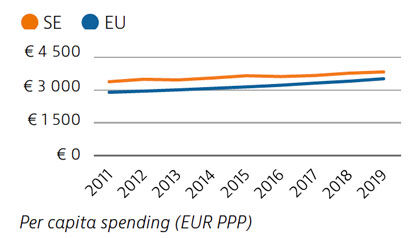

Health spending per capita in Sweden was the fourth highest in the EU in 2019, and the third highest in terms of health spending as a share of GDP. Most health spending is publicly funded (85%). The growth rate in health spending was relatively modest in the years prior to the pandemic, but the government increased spending on health in 2020 and 2021 in response to Covid-19.

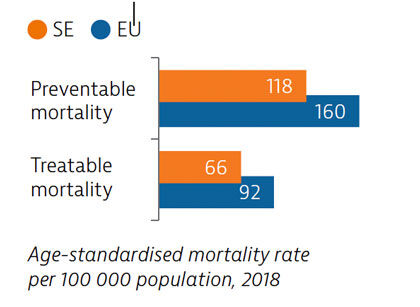

Sweden had low rates of mortality from preventable and treatable causes in 2018, pointing to a generally effective public health and healthcare system under normal circumstances.

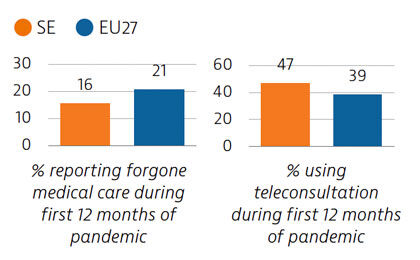

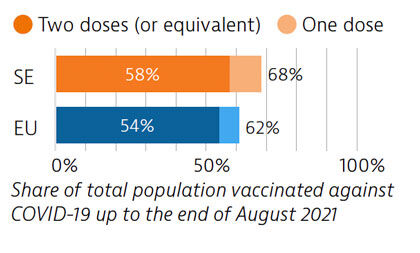

During the first year following the pandemic, one in six people in Sweden reported some unmet needs for medical care, which is slower than the EU average. The use of teleconsultations increased quickly in Sweden during the pandemic to maintain access to care.

Sweden tried to balance protection of people’s health and protection of economic and social activities in managing the Covid-19 crisis. While fewer restrictions were imposed, particularly during the first wave, the death toll was high compared with other Nordic countries. By end of August 2021, 58% of the population had received two doses or the equivalent – slightly more than the EU average.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Sweden: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

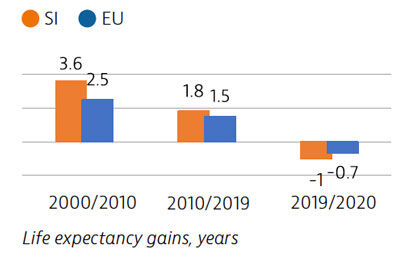

Life expectancy in Slovenia has increased markedly since 2000, but in 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily erased a year’s worth of gains. The Slovenian health system provides near universal coverage and a broad benefits package.

Voluntary health insurance plays a large role in covering co-payments levied on services; this also confers a considerable degree of financial protection from out-of-pocket payments.

The pandemic exacerbated or laid bare health system weaknesses, including workforce shortages, long waiting times, ageing hospital facilities and fragmented and underfunded long-term care.

Life expectancy in Slovenia had increased by over five years between 2000 and 2019. However, in 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic reversed this trend: life expectancy fell from 81.6 years in 2019 to 80.6 in 2020. Stroke, ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer are usually the main causes of mortality, but Covid-19 was responsible for the largest number of deaths in 2020.

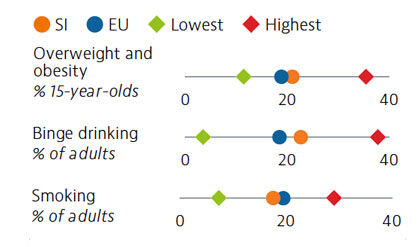

More than one fifth of Slovenian adolescents were overweight or obese in 2018. Alcohol intake among both adults and adolescents ranks above the average across EU countries, with binge drinking much more prevalent among male adults. Smoking prevalence has decreased for both adults and adolescents over the last decade, but over one in six adults are still daily smokers. The increasing popularity and use of e-cigarettes is also a concern.

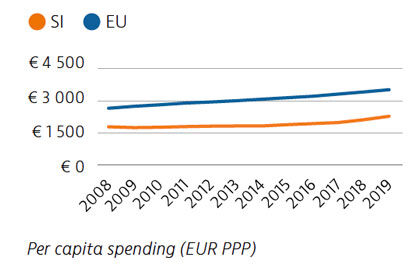

Health expenditure per capita has risen marginally over the last few years, but it remains well below the rate across the EU as a whole, as does spending as a share of GDP. Public financing of the health system accounted for 73% of health spending in 2019. Out-of-pocket spending is among the lowest in the EU, however, due mainly to extensive uptake of voluntary health insurance to cover co-payments.

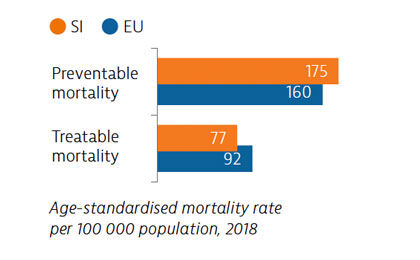

Mortality from preventable causes remains above the EU average. In contrast, mortality from treatable causes is lower than the EU average, indicating that the healthcare system is generally effective in providing care for people with potentially fatal conditions.

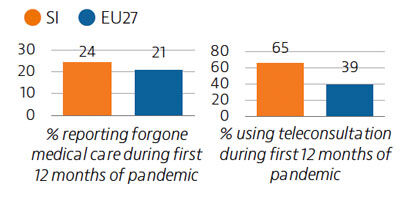

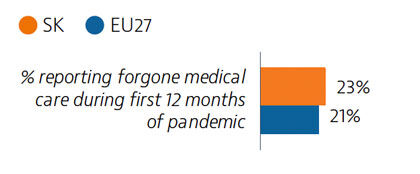

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, unmet needs for medical care were low, at 2.9% of the population, with waiting times the primary driver. In 2020, the demand for Covid-19-related care often led to delayed or forgone consultations and treatment for other health issues. Around 24% of the population reported forgone medical care during the first 12 months of the pandemic.

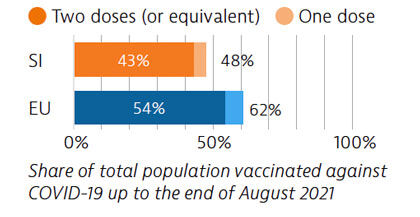

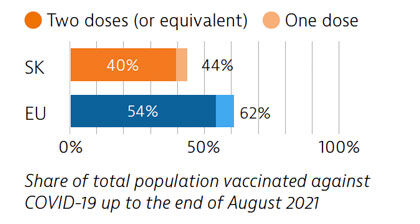

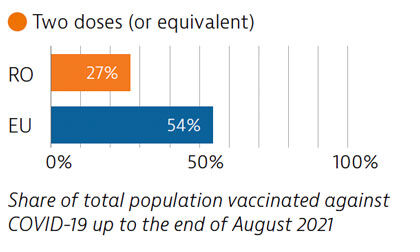

The Covid-19 pandemic revealed several resilience challenges, including workforce shortages and underdeveloped long-term care infrastructure prompting plans for more investment. Slovenia accelerated its vaccination campaign in spring 2021, and at the end of August 2021, 43% of the population had received two vaccine doses (or equivalent).

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Slovenia: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

3rd July 2023

Life expectancy in Slovakia is among the lowest in Europe, and temporarily fell by almost one year in 2020 due to the impact of Covid-19. Behavioural and environmental risk factors contribute to nearly half of all deaths.

The Slovak population enjoys a broad benefits package, which includes recently introduced telemedicine. However, low levels of health spending and health workforce shortages remain persistent issues that were exacerbated by the pandemic.

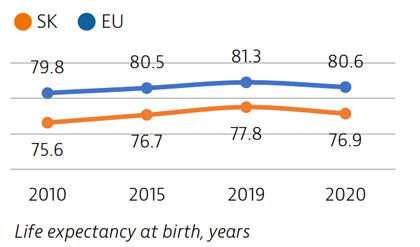

Life expectancy in Slovakia increased by more than two years between 2010 and 2019, only to fall by almost one year in 2020 due to Covid-19 deaths. It remains nearly four years below the EU average. Disparities in life expectancy by socioeconomic status remain among the largest in the EU. Slovakia also has one of the highest cancer mortality rates in the EU.

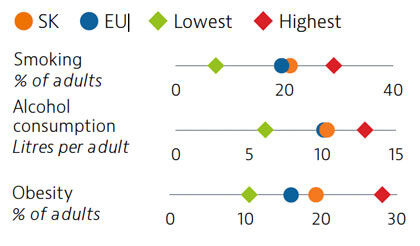

While adult tobacco consumption declined in most countries over the past decade, in Slovakia it remained stable and is currently above the EU average. Alcohol consumption is comparable to the EU average. Obesity rates among adults and adolescents are on the rise and higher than the EU average, due in part to poor nutritional habits and limited levels of physical activity.

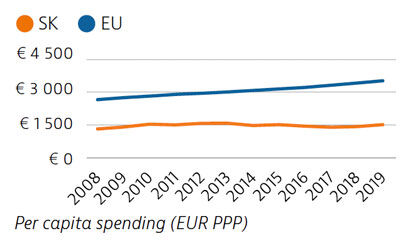

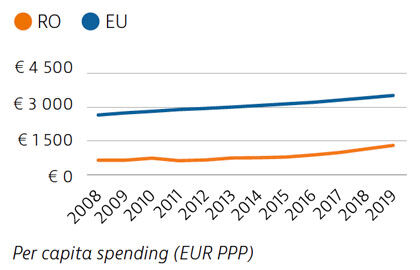

Slovakia spends less than half the EU average on health, at €1,513 compared to €3,521 per person in 2019, adjusted for differences in purchasing power. Around 80% of health spending is publicly financed, and out-of-pocket payments accounted for almost 20% of health expenditure in 2019 compared to 15.4% in the EU.

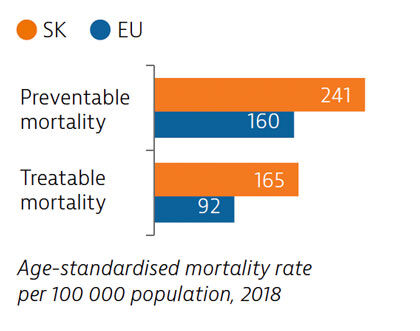

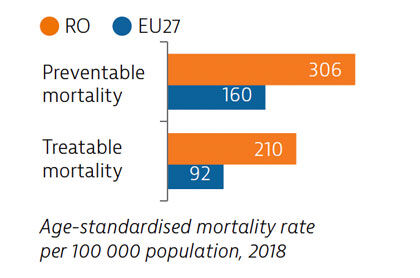

Slovakia has among the highest mortality rates from preventable and treatable causes in the EU. Despite improvements, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death. Substantial room for improvement remains for effective public health policies to reduce premature deaths.

Access to healthcare is generally good in Slovakia, with only 2.7% of the population reporting unmet medical care needs before the pandemic. However, during the first 12 months of the pandemic, 23% of people reported forgone medical care. The introduction of telemedicine helped to maintain access to care during the second wave of the pandemic.

Slovakia had low Covid-19 case numbers during the first wave of the pandemic, due in part to quick implementation of containment measures. However, numbers rose significantly during the second wave; three quarters of all Covid-19 deaths occurred in the first half of 2021. As of August 2021, 40% of the population had received two vaccine doses (or equivalent) – a proportion lower than the EU average.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Slovakia: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Life expectancy in Romania is among the lowest in Europe, and the Covid-19 pandemic reversed some of the gains made since 2000. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of strengthening primary care, preventive services and public health, in a health system currently heavily reliant on inpatient care.

Health workforce shortages and high out-of-pocket spending are key barriers to access. The Covid-19 pandemic stimulated the creation of several electronic information systems to manage overstretched health resources better, and these may offer avenues to future health system strengthening.

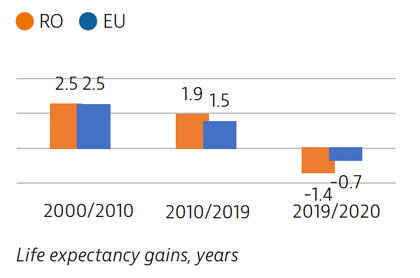

Life expectancy in Romania increased by more than four years between 2000 and 2019, but declined temporarily by 1.4 years in 2020 due to the impact of Covid-19. There is a marked gender gap, with women living almost eight years longer than men. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading causes of mortality while lung cancer is the most frequent cause of cancer death.

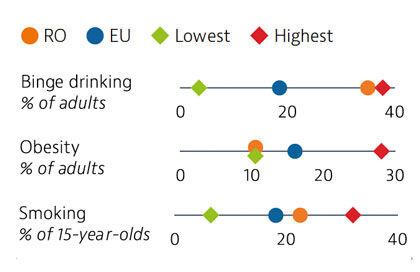

Risky health behaviours contribute to nearly half of all deaths. Romanians report higher alcohol consumption and unhealthier diets than the EU averages, but adult obesity is the lowest in the EU. Smoking in adults is now marginally lower than the EU average. These risk factors are more prevalent among men than women. Overweight, obesity and smoking rates among adolescents are high, and have been growing steadily over the past two decades.

Health spending in Romania increased in the last decade but remains the second lowest in the EU as a whole – both as a share of GDP and per capita. About 44% of health spending was allocated to inpatient care in 2019, which is the highest proportion among EU countries. Although the public share of health spending is high and in line with the EU average, out-of-pocket payments are above the EU average and are dominated by outpatient pharmaceutical costs.

The preventable mortality rate is the third highest in the EU and can be attributed mainly to cardiovascular disease, lung cancer and alcohol-related deaths. Mortality from treatable causes is more than double the average for the EU and includes deaths from prostate and breast cancers that are amenable to treatment.

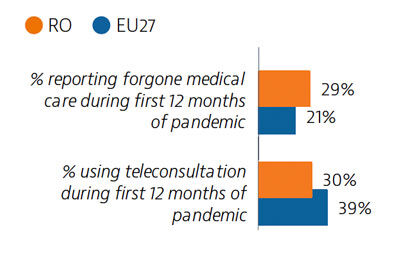

Although self-reported unmet needs for medical examinations had declined by more than half between 2011 and 2019, a high rate of forgone care was recorded in the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic. Teleconsultations were not used as widely as in other EU countries.

Before the pandemic, Romania invested significantly in the health sector, albeit from a low base, but Covid-19 put great pressure on the system. Planning and communication for the Covid-19 vaccination campaign began early, but the rollout was delayed due to supply shortfalls. Vaccination coverage is low, largely due to vaccine hesitancy.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Romania: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

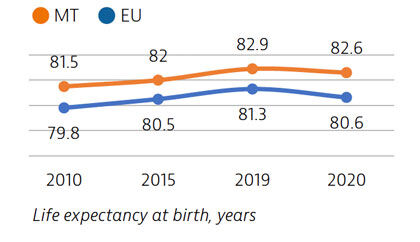

Life expectancy in Malta is the second highest among EU countries, but it declined in 2020 as a result of deaths during the Covid-19 pandemic. People spend more time living in good health compared to other EU countries, but rates of obesity are high and pose a major public health challenge.

Malta’s National Health Service provides good access to care, but the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted structural weaknesses in the health sector, including low hospital capacity, insufficient investment in prevention and gaps in the workforce.

Commitments to enhance the use of digital health, ongoing reforms to primary care and investment in physical infrastructure and the health workforce will help to build a more resilient healthcare system.

Life expectancy in Malta in 2020 was two years higher than the EU average. While it fell by 0.3 years due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this was below the average decline of 0.7 years seen across the EU. Deaths from cardiovascular disease and cancer have declined substantially in recent decades, but deaths from diabetes remain high. Self-reported good health among the population is high, but sizeable income-based inequalities in health status persist.

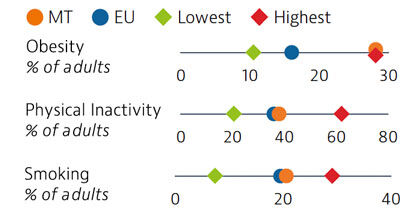

Rates of obesity in Malta are the highest in the EU, with more than a quarter of adults classified as obese. Poor diets and physical inactivity contribute to high levels of obesity in the country. Smoking rates among adults are similar to the EU average.

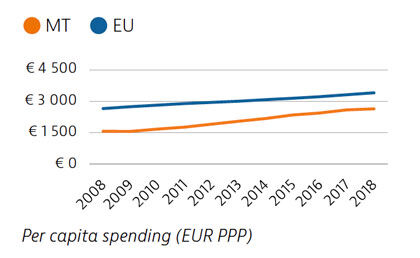

Malta has seen one of the largest increases in total health spending in the EU between 2008 and 2018, although expenditure per capita and as a share of GDP remained below the EU average in 2018. The share of funding from public sources also remained relatively low, and private out-of-pocket payments were among the highest in the EU. Public spending on health nevertheless increased substantially during the Covid-19 crisis.

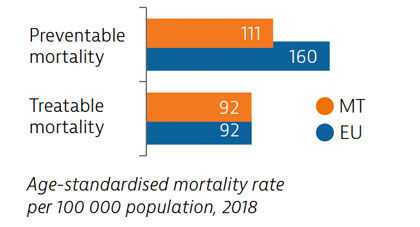

Mortality from preventable causes in Malta is among the lowest in the EU. Deaths from treatable causes have declined in recent years, and are now equal to the EU average. More deaths from cardiovascular diseases, cancers and diabetes could be avoided through more timely and effective diagnosis and treatment.

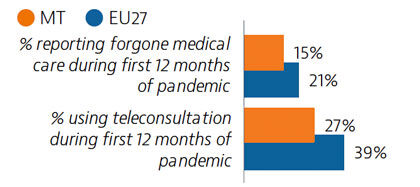

Malta’s health system provides good access to care, and levels of unmet needs for care were the lowest in the EU in 2019. One in six people reported having forgone care during the Covid-19 pandemic – a share lower than the EU average. Use of e-prescriptions, remote consultations and remote monitoring of Covid-19 patients helped maintain access to care during the pandemic.

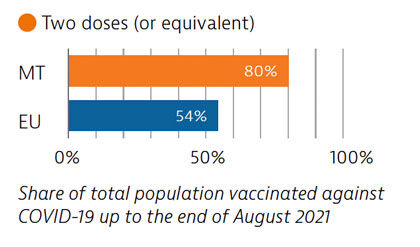

Widespread testing and comprehensive public health measures formed central components of Malta’s Covid-19 response. The country’s vaccination programme was also implemented rapidly, and by the end of August 2021, 80% of the population had received two doses (or equivalent) – the highest proportion in the EU at that time.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Malta: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Life expectancy in Portugal is slightly higher than the EU average, but it fell by nearly a year in 2020 because of deaths due to Covid-19.

While the Portuguese health system provides universal access to high-quality care, the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted some structural weaknesses, including low investment in the health workforce and equipment. However, the pandemic also stimulated several innovative practices that could be expanded to build a more resilient health system in the future.

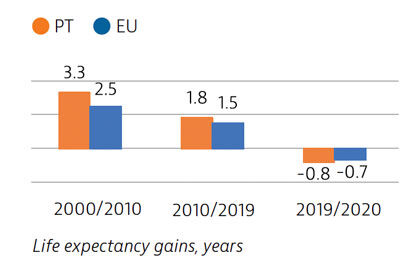

Life expectancy in Portugal in 2020 was half a year higher than the EU average, although it fell temporarily by 0.8 years between 2019 and 2020 because of deaths due to Covid-19 – a reduction close to the EU average. Before the pandemic, life expectancy in Portugal had increased by more than five years between 2000 and 2019. The burden of non-communicable diseases is high, and cardiovascular diseases and cancer are the leading causes of death.

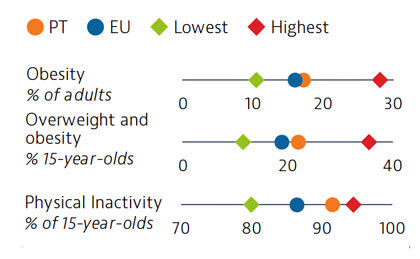

Approximately one third of all deaths in Portugal in 2019 can be attributed to behavioural risk factors. Overweight and obesity are growing public health issues among adults and young people. In 2018, 22% of 15-year-olds were overweight or obese, which is higher than the EU average. Low physical activity is one factor contributing to increasing rates of overweight and obesity

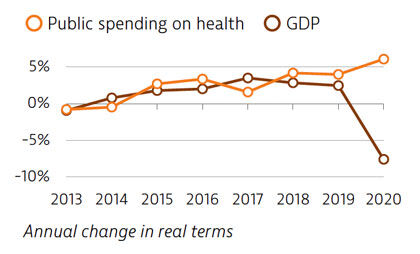

Spending on health per capita and as a share of GDP has been lower in Portugal than the EU average for many years. In 2019, Portugal spent €2,314 per capita on health, which is one third less than the EU average of €3,521, and health spending accounted for 9.5% of GDP (lower than the 9.9% EU average). The Covid-19 pandemic led to increased public spending on health in 2020, while the GDP fell sharply.

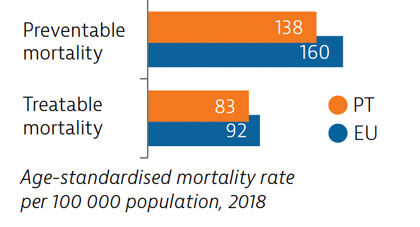

Mortality from preventable and treatable causes was lower in Portugal than the EU average in 2018. However, Portugal lagged behind some EU countries (such as Italy, Spain and France) on preventable mortality, suggesting that more could be done to save lives by reducing risk factors for leading causes of death such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

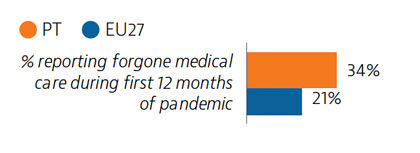

In 2019, a very small proportion of people reported some unmet medical needs due to cost, distance or waiting time, although this proportion was higher among those in the lowest quintile. Unmet medical care needs were much higher for all population groups during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, rapid expansion of teleconsultations helped maintain access to care during the pandemic.

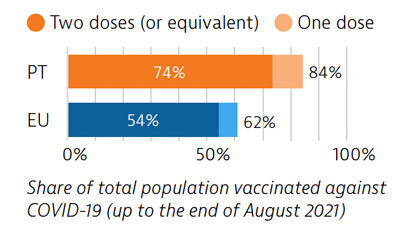

Portugal was among the EU countries hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. A broad testing strategy was supported by sufficient laboratory capacity, but containment of community transmission proved challenging. As of the end of August 2021, 74% of the Portuguese population had received two doses (or equivalent) of a Covid-19 vaccine.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Portugal: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.