This website is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Take a look at a selection of our recent media coverage:

17th July 2024

Diet and exercise interventions before and during pregnancy could lower cardiovascular risk in children, researchers have suggested.

Scientists at King’s College London (KCL) reviewed previous studies to examine the effectiveness of health interventions in obese women such as antenatal and postnatal exercise programmes and healthy diets for unborn children and the development of cardiovascular health.

Over half of women attending antenatal clinics in England and Wales are either obese or overweight, putting their unborn children at risk of heart issues in both childhood and later life.

The findings, published in the International Journal of Obesity, could help inform public health strategies and improve the heart health of future generations, the authors said.

The researchers reviewed existing data from sources such as PubMed, Embase, and previous reviews, to determine whether lifestyle interventions in pregnant women with obesity could reduce the chance of abnormal cardiac development in their offspring. In particular, they examined how the intervention could impact changes in the shape, size, structure and function of the heart, known as cardiac remodelling, and related cardiovascular parameters.

After screening over 3,000 articles, eight studies from five randomised controlled trials were included in the review. Diet and exercise interventions introduced during these trials included antenatal exercise (n = 2), diet and physical activity (n = 2), and preconception diet and physical activity (n = 1). The children in the studies were under two months old or between the ages of three and seven.

The researchers found that lifestyle interventions in obese women could benefit the heart health of children. Interventions led to lower rates of heart wall thickening, normal heart weight and a reduced risk of high heart rates.

In all the reviewed studies, reduced cardiac remodelling and reduced interventricular septal wall thickness were reported as a result of diet and exercise interventions. In some of the studies, the interventions in diet and exercise led to improved systolic and diastolic function and a reduced resting heart rate.

Dr Samuel Burden, research associate in the Department of Women and Children’s Health at KCL, said: ‘Maternal obesity is linked with markers of unhealthy heart development in children. We reviewed the existing literature on whether diet and exercise interventions in women with obesity either before or during pregnancy can reduce the impact of this and found evidence that these interventions indeed protect against the degree of unhealthy heart development in their children.’

The researchers suggested that longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and in older children are required to confirm these observations and to determine whether these changes persist to adulthood.

Dr Burden added: ‘If these findings persist until adulthood, then these interventions could incur protection against the adverse cardiovascular outcomes experienced by adult offspring of women with obesity and inform public health strategies to improve the cardiovascular health of the next generation.’

Evidence from The Academy of Medical Sciences earlier this year highlighted that early years health, which starts in pre-conception and goes through pregnancy and the first five years of life, is often overlooked in current policy but is crucial for laying the foundations for lifelong mental and physical health.

A version of this article was originally published by our sister publication Nursing in Practice.

1st September 2023

With lack of time often cited as a barrier to undertaking physical activity, cramming a week‘s worth of exercise into a day or two may seem more achievable, especially if it provides comparable cardiovascular benefits to a more evenly distributed pattern. Hospital Healthcare Europe‘s clinical writer and resident pharmacist Rod Tucker considers the evidence.

It is abundantly clear that being physically active is associated with health benefits. Current guidance on physical activity for adults in most major countries in Europe is broadly similar: undertake either at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity a week or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity, plus two days a week of strengthening activities to work all of the main muscle groups.

Moreover, it is advocated that exercise is undertaken every day or spread evenly over four to five days a week.

But is there any evidence that achieving this amount of exercise is associated with health benefits? In a 2020 study, an international research group tried to answer this question.

The team looked at the association between attainment of the recommended amount of physical activity among a representative sample of US citizens, and all-cause and cause specific mortality.

Their analysis included 479,856 adults who were followed for a median of 8.75 years. The findings were very clear: undertaking the recommended amounts of physical activity reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 40%. But not only that, such levels of activity lowered the risk of cardiovascular disease by 50% and the risk of cancer by 40%.

With clear evidence of the health benefits from undertaking the recommended levels of physical activity, surveys have also identified some notable and recognised barriers to exercising. One of the most consistently reported barriers is sufficient time to exercise, and this is seen irrespective of age and gender.

Although healthcare professionals may advocate that their patients engage in exercise as part of the health promotion message, it seems they don‘t always practise what they preach. In fact, research shows that lack of time is also a perceived barrier to exercise among doctors and nurses.

As well as insufficient time, a demanding workload gives rise to high levels of burnout and stress, and changing shift patterns can limit time and motivation, which all represent additional barriers to exercising among clinicians.

Evidence suggests that exercising for just one or two days a week could accrue the same health benefits seen among those who exercise more regularly throughout the week. For example, so-called ‘weekend warriors‘ – those who restrict physical activity to just one or two sessions per week – have a similar level of all-cause mortality compared to those who spread their physical activity over several days.

In fact, a 2023 meta-analysis of four studies with 426,428 participants found that the risk of both cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality in those compressing their activity into two days was 27% and 17% lower, respectively, when compared to those who were inactive.

However, a limitation of this analysis was that levels of physical activity were self-reported and therefore prone to misclassification bias.

With inherent self-reporting bias an issue, a recent study examined the value of accelerometer-derived data. Researchers recently set out to examine the association between a weekend warrior pattern of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) achieved over just one to two days, compared to the activity being spread more evenly, with the risk of incident cardiovascular events.

The researchers retrospectively analysed a UK Biobank cohort who provided a full week‘s worth of wrist-based accelerometer physical activity data. Individuals were classified into three groups: active weekend warriors, in which more than half of their total MVPA was undertaken over one to two days; regularly active, where exercising was spread throughout the week; and inactive, where less than 150 minutes of MVPA per week was undertaken.

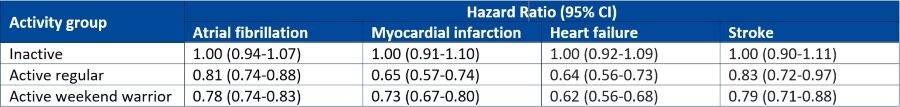

They looked at associations between the different activity pattern and cardiovascular outcomes such as incident atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke. The findings were then adjusted for several potential covariates including age, sex, ethnicity race, alcohol and smoking and diet quality.

Data for 89,573 individuals with a mean of 62 years (56% female) were included in the analysis and who were followed for a median of 6.3 years. Interestingly, when stratified at the threshold of 150 minutes or more of MVPA per week, nearly half of the entire cohort (42.2%) were classed as weekend warriors.

The findings for atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke are summarised in the table below.

The accelerometer-derived study shows that engagement in physical activity, regardless of the pattern, is able to reduce the risk of a broad range of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, although many healthcare professionals‘ working weeks may not permit specific exercising days, it seems that compressing physical activity into just two days per week, wherever possible, still achieves comparable health benefits.

So, whether it’s advice for patients or the foundation for personal fitness goals, the key message is to just keep moving.

13th April 2023

Dr Hannah Douglas is a consultant cardiologist specialising in adult congenital heart disease at Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. She is also the lead cardiologist for heart disease in pregnancy, works on the pulmonary hypertension team and runs a private practice at London Bridge Hospital HCA Healthcare.

Dr Douglas tells Hospital Healthcare Europe why heart disease in pregnancy is on the rise, the impact this has on services and what needs to be done to manage it.

17 years. I graduated in 2006 and obtained my primary medical degree from Queen’s University Belfast. Most of my medical training was at the Royal Victoria Hospital in the city. I then went to work at St Thomas’ Hospital in London as a subspecialty fellow in congenital heart disease. My additional skills include transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography, which help clarify complex diagnoses and support procedures such as cardiac surgery and catheter lab interventions.

During my placements as a junior doctor, I was torn between both cardiology and obstetrics and gynaecology. I had some really challenging experiences with difficult high-risk patients during both rotations, but I enjoyed the nature of the work and the patient cohorts. I’ll never forget the pregnant lady who suffered a cardiac arrest due to an undiagnosed, underlying heart condition. It was a completely formative experience in my training as a junior doctor and, without a doubt, influenced my career choices. I realised that I could marry the two specialties by training towards congenital heart disease, which has always been the traditional pathway to access obstetric cardiology or heart disease in pregnancy care.

Heart disease is the leading cause of maternal death in the UK. There remains a healthcare gender gap between men and women, which becomes extremely visible in cardiovascular disease within female-centred fields such as antenatal and obstetric care. I see a significant proportion of the population with undiagnosed conditions, such as cardiomyopathies or heart muscle disorders, which may be asymptomatic but then destabilise due to the added cardiac demands of pregnancy.

The number of women who are of advanced maternal age coming through antenatal care is rising, which means we see an increase in the risk of complications such as high blood pressure, pre-eclampsia and cardiac events during pregnancy.

Acquired heart disease – which traditionally affected older people – also seems to be increasingly present in younger and younger members of the population due to social, demographic and lifestyle issues that increase cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Preventative medicine is not necessarily considered top of the priority list, so there are issues with resources, and there are huge healthcare cost implications, too. We can see multidisciplinary teams of up to 25 to 30 healthcare professionals managing a single woman with a high-risk cardiovascular condition so that we can deliver her and her baby safely in the correct environment.

Busy! Guy’s and St Thomas’ is a tertiary centre university teaching hospital in central London. I’m part of a large cardiovascular department comprising cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. We are a Level 1 adult congenital heart disease cardiac surgical centre and have a pregnancy heart team.

Across my week I am involved in acute inpatient cardiology work, outpatient clinics which comprise general cardiology, adult congenital heart disease and antenatal cardiology, theatre and catheterisation lab support, and frequent strategy, policies, planning and education meetings.

Within the fields of adult congenital heart disease and heart disease in pregnancy, I am what is described as an imaging cardiologist. I perform ultrasound-based imaging diagnostic tests to guide decision-making, monitor longer-term consequences of previous cardiac surgery, look at disease progression and support procedural interventions, such as keyhole type or trans-catheter procedures in the cath lab, but also in open heart surgery. Here, I help to evaluate before and after an operation as to what needs to be done and the repair work that has been done, working closely with my colleague cardiac surgeons.

At my practice in London Bridge Hospital, I look after patients with a range of general cardiac conditions, but I also see patients for pre-pregnancy risk assessment and counselling in women of childbearing age who may require optimisation of cardiovascular health before embarking on pregnancy.

Within the field of adult congenital heart disease, some of the most innovative procedures performed are trans-catheter redirection of complex holes in the heart. This gives our patients additional options other than open-heart bypass surgery.

My main research areas are related to cardiomyopathy in pregnancy and placental dysfunction, focusing on long-term cardiovascular outcomes in women with cardiovascular disease. I was part of a team that jointly published a paper on the prevalence of pre‐eclampsia and adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with pre‐existing cardiomyopathy.

It was a large, multi‐centre retrospective cohort study that found a modest increase in pre-term pre-eclampsia and a significant increase in foetal growth restriction (FGR) with pre-existing cardiac dysfunction. It found that the mechanism underpinning the relationship between cardiac dysfunction and FGR merited further research but could be influenced by concomitant beta blocker use.

Another paper I’m working on, which hasn’t been published yet, is the new British Society of Echocardiography Guidelines for the Pregnant Patient, which will be adopted as UK guidance for cardiac ultrasound scanning pregnant women with heart conditions.

Yes, we have constant fellowship posts across a range of sub-specialties within cardiology to include adult congenital heart disease.

Most of our fellows come from other parts of Europe and Asia where we build links with large international institutions to develop our own skills. We also provide additional experience to doctors towards the end of their training who require extra expertise or are planning to develop services similar to ours in other places.

There is an active research department within cardiology, and, in addition to this, we are at the forefront leading in complex surgical and trans-catheter interventions on patients of all ages and all types of congenital and acquired heart disease backgrounds.

Patient volume will continue to challenge us. We are growing in all areas of cardiology and specifically within the heart disease in pregnancy service. The number of patients we see face to face in the clinic and look after for antenatal surveillance is expanding all the time.

We also have a hub-and-spoke type sector-wide system whereby we reach out to train and support our colleagues in peripheral hospitals so that care can be delivered to women of perceived lower risk closer to home.

Challenges will continue within education and training, which needs to be constant and run rotationally, as well as staff turnover. We must educate medics, nursing staff, physiologists, midwives, interventionalists and anaesthetists – the list is endless. They need to be empowered to challenge their own learning and to recognise subtle or early risk factor signs. These might have important implications in minimising risks for women with a heart condition or who may develop a heart condition during pregnancy.

It is the responsibility of anyone who looks after women of childbearing age from menarche to menopause to address risk factors, contraception and family planning.

We also sometimes struggle to engage patients with this process – optimising women’s health before pregnancy is our long-term goal. Patients are getting older and sicker.

In pregnancy, we see increased advanced maternal age all the time. This is a complex caseload of patients, which will only continue to increase, and, therefore, the risks will increase with the patients.

It is, however, our privilege to provide such a service, and we never back down from a challenge!

Explore the latest advances in clinical care, delivered by renowned experts from recognised Centres of Excellence, at the HHE Clinical Excellence in Cardiovascular Care event on 10 May 2023. Find out more and register for free here.

15th March 2019

With high intensity interval training gaining in popularity, does the evidence suggest there are safe and effective cardiovascular health benefits for this type of exercise? Rod Tucker investigates.

The NHS has described exercise as a miracle cure that is able to reduce the risk of major illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes and even cancer.

In order to achieve these benefits, the UK Government’s guidelines recommend that adults aged between 19 and 64 should undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activities, such as cycling or brisk walking, every week, combined with strength training on two or more days per week. Sadly, this message is not filtering through to he general public.

A report by the British Heart Foundation suggested that physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles cost the NHS as much as £1.2 billion a year and around 39% of adults (about 20 million people) fail to meet the Government’s physical activity targets. There are a range of possible reasons for this but one that is consistently reported among those who are not sufficiently active is lack of time.

One potential solution to achieving the same benefits of exercise in a much shorter space of time that is gaining in popularity is high intensity interval training (HIIT), which involves intermittent periods of intense exercise, i.e. going flat out, separated by periods of recovery.

In recent years, the value of HIIT as an exercise intervention has been extensively researched and compared to moderate intensity continuous training (MICT) such as jogging or cycling. The consensus appears to be that HIIT offers comparable health benefits to MICT. Furthermore, according to a new systematic review and meta-analysis of 786 studies, HIIT produced a 28.5% greater reduction in fat loss compared to MICT.

Many of the HIIT studies have been short-term and undertaken in laboratories using expensive exercise equipment. So, how transferable are these results to the real-world?

One recent ‘real-world’ 12-month study of adherence to HIIT in overweight adults sought to answer to this question. Participants could select HIIT or MICT as an exercise intervention and the results showed that adherence to HIIT reduced from 60% to 19% by 12 months. Nevertheless, for those who continued with HIIT, health outcomes were equivalent to those assigned to MICT.

But how safe or effective is HIIT for the majority of people who are likely to have a range of long-term health problems including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and are generally older. And should pharmacists be recommending this form of exercise?

This has been the subject of much scientific scrutiny with one review suggesting that HIIT may improve fitness and should be a component of the care for those with coronary artery disease. Similarly, HIIT improved glycaemic control, body composition, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and was beneficial in patients with heart failure and even older people.

While this research indicates the value of HIIT for patients with a range of health conditions, pharmacists should ensure that customers seek advice from their GP before embarking on HIIT.

Finally, HIIT is not without problems and exertional rhabdomyolysis (dissolution of muscle) has been reported in people who participate in vigorous and intense spinning classes. Nevertheless, the growth of HIIT gym classes is testament to the popularity of this form of exercise for achieving improvements in health and fitness but in the least amount of time.