This website is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Take a look at a selection of our recent media coverage:

3rd December 2021

For further information on rheumatology, please click here for the latest clinical news and updates’.

9th November 2021

For further information on emergency care, please click here for the latest clinical news and updates’.

2nd November 2021

Support for the development of this article was provided by Sight Diagnostics

In emergency departments (EDs), rapid and accurate COVID-19 screening is critical for effective infection control and ensuring timely – and appropriate – delivery of care for patients. With the pandemic relentlessly exerting an unprecedented burden on the healthcare system worldwide, this call for fast identification of COVID-19 at the point of care is more urgent than ever.

Currently, the nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR test – the gold standard for SARS-CoV-2 testing – has a few limitations, including a long turnaround time (12–24 hours), limited sensitivity and requiring laboratory infrastructure.1 The rapid lateral flow antigen detection test yields results faster, but has other limitations such as poor sensitivity. For example, in a study in Liverpool, the overall sensitivity of the rapid test was only 40.0%, i.e., the test only detected four in 10 people who tested positive by PCR.2 And due to this risk of false results and imprecisions in the manufacturer’s accuracy claims, the US Food and Drug Administration recalled and withdrew the rapid tests from sale in the US in June 2021.3

Because it is vital to make quick decisions about a patient’s care pathway (admission, treatment approach, discharge, etc.) while keeping the hospital environment safe, there is a system-wide operational and safety impact when effectively performing front-door COVID-19 triage in the ED.

The CURIAL algorithm – developed by infectious disease and machine learning experts at Oxford University – is a viable alternative to traditional testing that can successfully rule out COVID-19 within the first hour of a patient’s arrival at an emergency department. The CURIAL AI algorithm uses the data from routine CBCs, urea and electrolyte tests, vital signs, liver function tests, C-reactive protein (CRP) tests and blood gas to predict the probability of a patient testing positive for COVID-19.4

Therefore, to combat the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 while providing high-quality care to patients – all within a reasonable timeframe – CURIAL can be an effective, and faster, solution to triage patients for COVID-19 in the ED setting.

CURIAL developed two models to predict COVID-19 in patients: The ED model (for all patients visiting the ED) and the admissions model (for subsequently admitted patients). The training data, gathered from four teaching hospitals in Oxfordshire, assessed 155,689 adult patients at Oxford University Hospitals between 1 December 2017 and 19 April 2020. When calibrated during training to a sensitivity of 80% – the ED model attained 77.4% sensitivity and 95.7% specificity for identifying COVID-19 patients among all patients presenting to hospital. And correspondingly – with the same calibration – the admissions model achieved 77.4% sensitivity and 94.8% specificity. In terms of negative predictive values (NPVs) – the probability that patients with a negative result truly don’t have COVID-19 – both models achieved high NPVs (>98·5%) across a range of prevalences (≤5%), allowing for a quick and reliable rule-out.

During a real-world evaluation of the CURIAL models over a two-week test period (20 April–6 May 2020) in Oxford University Hospitals’ EDs, CURIAL displayed impressive accuracy. The ED model (3326 patients) achieved 92.3% accuracy (NPV 97.6%), and the admissions model (1715 patients) achieved 92.5% accuracy (NPV 97.7%) in comparison to PCR results.4

To understand which individual features had the most significant influence on model predictions, CURIAL ran a relative feature importance analysis. For both models, eosinophils and basophils had most significant effects on model performance,4 meaning complete blood counts directly impact the CURIAL algorithm’s success.

As effective AI-powered COVID-19 screening relies on time-sensitive and accurate CBC results, the University of Oxford researchers created a version of CURIAL, called CURIAL-Rapide, that leverages only CBC results and vital signs to screen for COVID-19 in patients. Consequently, CURIAL-Rapide creates a new collaborative pathway where point of care CBC analysers – such as Sight Diagnostics’ OLO haematology analyser – are used in conjunction with CURIAL to potentially further expedite the overall screening turnaround time. And when the analyser can provide rapid results with lab-grade accuracy – OLO produces accurate results in approximately ten minutes – it can play a pivotal role in ensuring a safer hospital environment by triaging COVID-19 patients efficiently. For example, by reconfiguring the care pathway and removing the time and logistical constraint of using conventional lab infrastructure, hospitals can create separate areas (hot-labs) for CBC testing before patients enter EDs to reduce operational strain and staff work time while keeping the hospital safe from COVID-19 transmission.

To substantiate this innovative pathway and the CURIAL-Rapide algorithm, the University of Oxford deployed OLO analysers at the John Radcliffe Hospital in February 2021 to power lab-free screening. The study’s interim evaluation was successfully completed, and results will be published soon.

Having accurate CBC results in minutes, from OLO, would help CURIAL-Rapide make predictions even sooner, potentially reducing care delays and supporting infection control within hospitals. Our goal is to get the right treatment to patients sooner by helping rule out COVID at triage for a majority of patients who don’t have the infection. This project shows that artificial intelligence can work with rapid diagnostics to help us select the best care pathways and minimise risks of spreading the infection in hospitals.5

Andrew Soltan, academic clinician and machine learning researcher at Oxford University

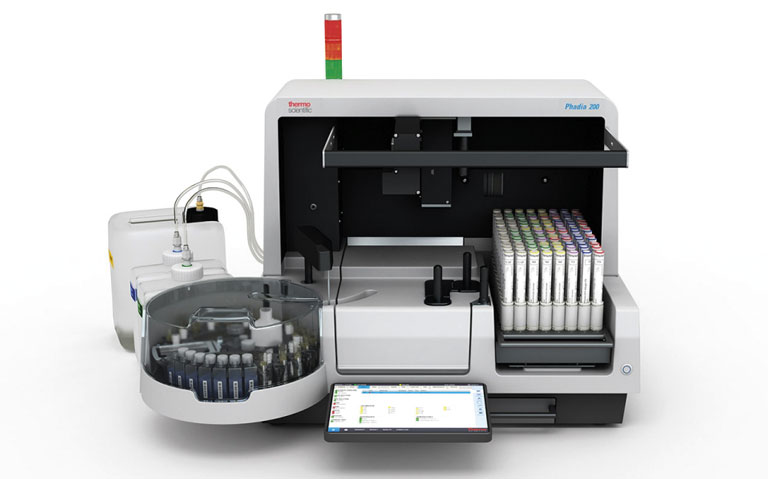

Sight OLO haematology analyser streamlines the typical blood staining workflow while maintaining lab-grade accuracy. Through a quick finger prick and the culmination of cutting-edge innovations in physics, optics, sample preparation, and an AI-based computer vision algorithm, the self-contained quantitative multi-parameter analyser can deliver fast and accurate CBC results within minutes in point of care settings.

During a recent study, the accuracy of OLO was compared with the Sysmex XN-1000 System. Samples – covering a broad clinical range for each tested parameter – from 355 males (52%) and 324 females (48%) aged 3 months to 94 years were analysed. The regression analysis results showed a consonance in correlation coefficient and slope, bias and intercept between OLO and Sysmex XN. Therefore, the study concluded that OLO performs with high accuracy for all CBC parameters,6 thus, making OLO the perfect partner to use alongside an AI COVID-19 screening initiative, such as CURIAL.

Learn more about CURIAL’s rapid identification of COVID-19 and CBC results’ role in improving ED patient flow in a Sight Diagnostics CURIAL webinar. Register at www.sightdx.com/events/curial-rapide to watch the full webinar.

11th October 2021

Support for the development of this article was provided by Sight Diagnostics

There is a constant and delicate balance throughout the oncology care pathway between time, high-quality oncological care, efficiency as a cancer centre, and cost ratios. All these considerations are connected and kept in equilibrium by one routine step – complete blood counts (CBCs). Unfortunately, because oncology blood tests are frequent (48–72 hours before each chemotherapy cycle) and legacy haematology processes (drawing blood, transporting the sample, receiving results, accessing results, etc.) with a centralised laboratory can take hours, CBCs often cause a bottleneck in the oncology ecosystem. This domino effect causes delayed treatment, scheduling complications, vacant chairs, unproductive clinic operations, and patient safety concerns, leading to high operating costs for care providers, substandard patient experiences, and unsatisfactory treatment outcomes. These inefficiencies are at times even further intensified by broken lab equipment (especially in smaller oncology settings), limited lab operational hours (weekdays nine to five), and poor-quality point of care haematology analysers that struggle with abnormal samples, which all culminates in blood being sent out to hospital labs for testing. This results in additional travel time, no internal flagging system, and potentially outdated blood results.

According to Professor Richard Adams, Professor and Honorary Consultant Clinical Oncologist at Cardiff University and Velindre Cancer Centre, Cardiff, UK, when the oncology system’s workflow is slow or broken – and a patient arrives at a clinic and does not receive treatment – it not only negatively affects the intensity of the chemotherapy but also has a profound financial and operational impact on many stakeholders as well: “We’re looking at about 16 people in the network of things. And let’s then bring in the doctor, the specialist nurses, the communication with the patient, the uncertainty for the patient, the time the patient took to travel there, the likelihood that they came with somebody else, the likelihood that person took time off work. So, the knock-on effect becomes quite extensive if you have a delay for an individual patient in this sort of circle of events.”

Furthermore, Professor Adams stresses that a lot can change between when the blood tests are done and when the patient is scheduled to receive treatment. With borderline neutropenic patients especially, this often leads to clinicians making judgment calls on whether they suspect the trajectory of the neutrophils to be up or down, which can pose a significant risk in terms of ensuring the safety of the treatment: “That’s where we run into challenges in terms of optimising safety, and where something that gave us a very rapid turnaround would allow us potentially to continue to use a slot that otherwise goes vacant, keeps us efficient, keeps the intensity of the chemotherapy up, and also keeps the chemotherapy delivery safe for an individual.”

As Professor Adams highlights, reliable, non-compromising haematology analysers at the point of care can positively address many system inefficiencies. That is, if a point of care CBC analyser ticks the following criteria: can provide lab-grade accuracy within a quick turnaround time; is easy to set up and operate; requires minimal training and low maintenance; and can leverage a finger prick sampling method as well as a venous one (which requires a trained phlebotomist), it can transform the efficiency of the oncology care pathway.

From an operating costs perspective, by reconfiguring the oncology blood test workflow with an accurate point of care CBC analyser, it could not only reduce lab downtime, ‘out-of-hours’ samples, and backlogs, but also help reduce turnaround times, vacant chemotherapy chairs, patient travel costs, staff hours, and unnecessary expenditure – which may lead to cost savings for every stakeholder in the oncology ecosystem.

From a patient’s perspective, by incorporating an accurate and rapid point of care CBC analyser throughout the oncology journey, it could help optimise treatment safety, maintain the intensity of the chemotherapy, and provide patients with high-quality care physically and psychologically – all of which could contribute to a better patient experience and more satisfactory treatment outcomes.

“In terms of safe and better quality standards, I think the closer you can get that blood count to the actual delivery of the chemotherapy, the better.”

Professor Richard Adams,

Honorary Consultant Clinical Oncologist at Cardiff University and Velindre Cancer Centre, Cardiff, UK.

Because oncology care depends on time-sensitive, yet accurate (especially at low ranges) CBC results, the Sight OLO haematology analyser streamlines the typical blood staining workflow while maintaining lab-grade accuracy. So, through leveraging innovations in physics, optics, sample preparation, and AI-based computer vision algorithms, the self-contained quantitative multi-parameter analyser and its disposable cartridge can deliver fast and accurate CBC results within minutes in point-of-care settings. To test OLO’s performance, Sight ran numerous studies to compare OLO to legacy analysers.

In a Sight report summarising the accumulated results from 17 clinical method comparison studies focusing on low counts for clinically significant CBC parameters, OLO also showed excellent performance in enumerating low ranges (Table 1 and Figs 1 and 2). The studies compared the performance and accuracy of OLO to comparative haematology analysers (for example, Sysmex XN and Beckman Coulter DxH models) at various institutes and clinical settings – including oncology departments – in different countries. Again, the high agreement between OLO and the comparative analysers demonstrated OLO’s compatibility to oncological contexts. And the versatility of technologies, locations, operators, and clinical settings confirmed the robustness and accuracy of OLO across different variables.

During one study conducted in November 2020 in an oncology day centre in Israel, Sight evaluated OLO’s accuracy for finger prick samples across OLO’s reportable range and the device’s workflow and turnaround time compatibility to the centre. The study’s 64 patient sample enrolment aimed to cover low ranges for specific measures, particularly relevant for oncologic patients’ medical decisions.

The results of the study showed very good correlations between the different sampling methods and analysers in a variety of oncology patients while covering a wide range of values. The finger prick results also demonstrated excellent accurate reporting of actionable results, with approximately 90% of the samples having no flags on main parameters. And an OLO and Beckman Coulter DxH800 (the centre’s current system) comparison revealed OLO decreased the average time from phlebotomy to CBC results by 45%.

Overall, the various studies demonstrate that the high rate of accurate results suggests that using OLO in an oncology setting could help make clinical decisions in real-time, improve workflow efficiencies, and provide reliable and accelerated care to patients.

This article is intended for global dissemination excluding audiences in the US.

11th June 2021

Patients can be at risk from ultrasound-associated infections when low-level disinfection (LLD) is the standard of care. In order to quantify this risk, Scotland’s National Health Service undertook a retrospective analysis of microbiological and prescription data through linked national health databases. Patient records were examined in the 30-day period following semi-invasive ultrasound probe (SIUP) procedures.

The study analysed almost one million patient journeys that occurred during a six-year period from 2010.1

Of the 982,911 patients followed, 330,500 were gynaecological patients; and 60,698 of these gynaecological patients had undergone a transvaginal (TV) ultrasound procedure. These patients were found to be at a 41% greater risk of infection and a 26% greater risk of needing an antibiotic prescription in the 30 days following their transvaginal ultrasound procedure when compared to gynaecological patients who had not undergone a transvaginal ultrasound.

During the study period, 90.5% of facilities reported that they were performing low level disinfection for transvaginal ultrasound probes. These patients were at a greater risk of infection due to inadequate reprocessing and the study concluded that: “Hence failure to comply with existing guidance on [high-level disinfection] of SIUPs will continue to result in an unacceptable risk of harm to patients .”1

The diverse use of ultrasound probes is now prompting a renewed focus on correct probe reprocessing to ensure patient safety. To ensure best practice standards, decontamination experts and ultrasound users need to work together to reduce the risk of infection that is associated with using ultrasound probes.

Ultrasound procedures are performed in various inpatient and outpatient settings by a wide range of health professionals. This has increased the use of surface probes to guide procedures such as biopsies, cell retrieval, cannulation, catheterisation, injections, ablations, surgical aspirations, and drainages. Across these procedures, the probe has the potential to contact various patient sites – including intact skin, non-intact skin, mucous membranes and sterile tissue. This presents a complex challenge, as contact with these various body sites requires differing levels of disinfection or sterilisation between patient uses. Failure to adequately clean and disinfect medical devices like ultrasound probes between patients poses a serious risk to patient safety.

In 2012, a patient in Wales died from a hepatitis B infection – most likely caused by a failure to appropriately decontaminate a transoesophageal echocardiography probe between patients. As a result of this fatality, a Medical Device Alert was issued by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (UK) advising users to appropriately decontaminate all types of reusable ultrasound probes.2

The UK and European guidelines require ultrasound probes that come into contact with mucous membranes and non-intact or broken skin to be high-level disinfected. In particular, automated and validated processes for ultrasound reprocessing are preferred. This is supported by a study relating to manual disinfection methods, which found that only 1.4% of reprocessing systems were fully compliant when using manual methods, compared to 75.4% when using semi-automated disinfection methods.3

The Spaulding classification system4 must be applied before a procedure commences so that information about what tissues or body sites may be contacted is taken into account.

This classification system is a widely adopted disinfection framework for classifying medical devices, based on the degree of infection transmission risk, and requires the following approaches:

It is important to note the difference between cleaning and low-level disinfection. Cleaning is the removal of soil and visible material until the item is clean by visual inspection. Low level disinfection is the elimination of most bacteria, some fungi and some viruses.

A final and important point for consideration is the use of probe covers.

While many ultrasound users and sonographers believe that their transvaginal ultrasound patients are protected from infection risk by using barrier shields and/or condoms, research has shown that up to 13% of condoms fail and up to 5% of commercial covers fail. Probe covers may have microscopic tears or breakages which can allow microorganisms to pass through.5

Ultrasound users should work with their decontamination colleagues to understand the current UK and European guidelines for reprocessing ultrasound probes. There are patient risks associated with ultrasound usage when proper disinfection procedures are not followed, as well as from ancillary products such as contaminated ultrasound gel. While the increased use of ultrasound has brought many benefits for patients, effective education and disinfection protocols are required to minimise the risk of infection.

The trophon® system is designed to reduce the risks of infection transmission through automated high-level disinfection of transvaginal, transrectal and surface probes. With over 25,000 units operating worldwide, 80,000 people each day are protected from the risk of cross-contamination with trophon devices. As a fully enclosed system, trophon2 can be placed at the point of care to integrate with clinical workflows and maintain patient throughput. trophon technology# uses proprietary hydrogen peroxide disinfectant that is sonically activated to create a mist. Free radicals in the mist have oxidative properties enabling the disinfectant to kill bacteria, fungi and viruses. The mist particles are so small that they reach crevices, grooves and imperfections on the probe surface. Nanosonics works collaboratively with probe manufacturers to carry out extensive probe compatibility testing. More than 1000 surface and intracavity probes from all major and many specialist probe manufacturers are approved for use with trophon devices.

# The trophon family includes the trophon EPR and trophon2 devices which share the same core technology of sonically-activated hydrogen peroxide.

9th January 2020

For a number of years, hospitals have been required to act more efficiently and to increase productivity. Increased performance is indeed evident. Yet, healthcare systems are facing conflicting trends: short and long-term impacts of financial and economic restrictions; increasing demands of an ever-expanding and ageing population, which leads to more chronic patients; increasing request and availability of technological innovations; new roles, new skills and new responsibilities for the health workforce.

To adapt to this situation, the role of hospitals is further evolving. Most health systems have already moved from a traditional hospital-centric and doctor-centric pattern of care to integrated models in which hospitals work closely with primary care, community care and home-care.

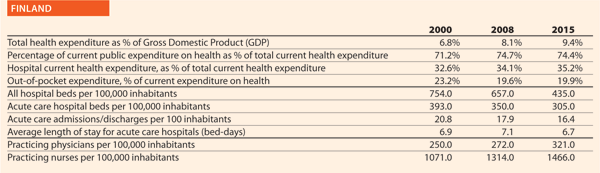

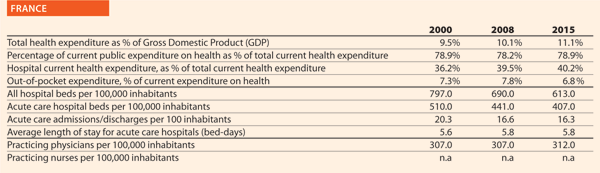

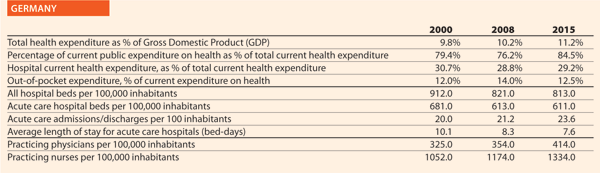

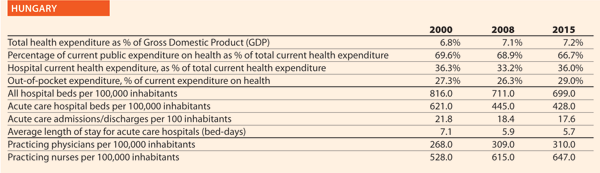

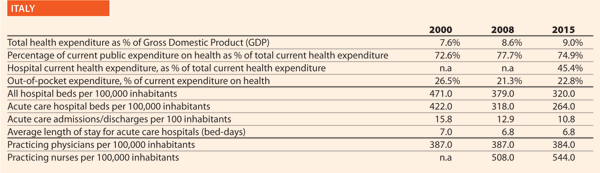

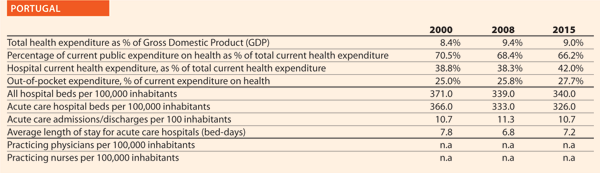

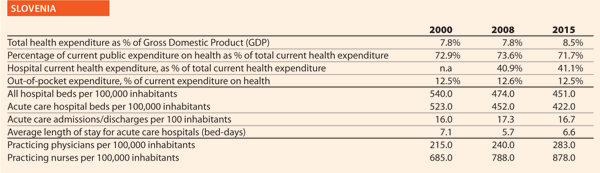

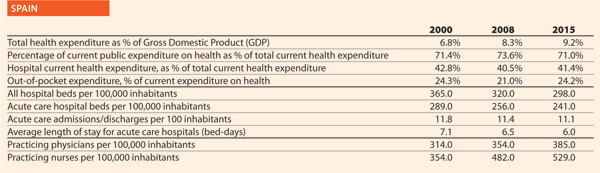

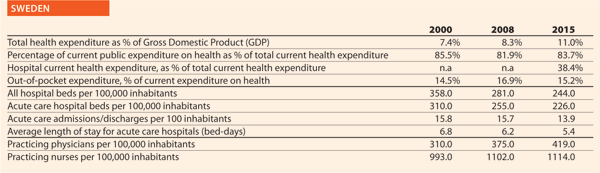

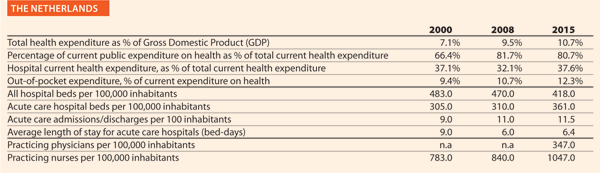

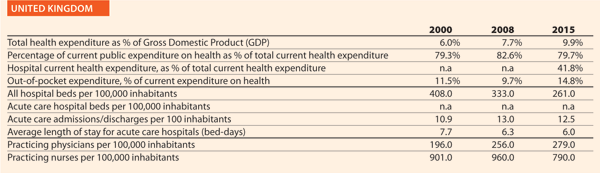

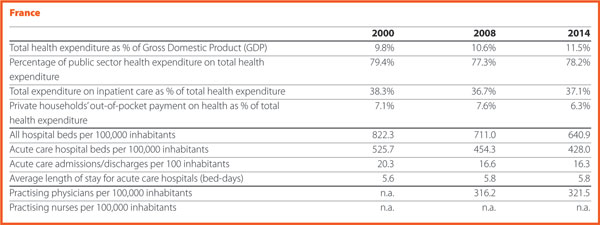

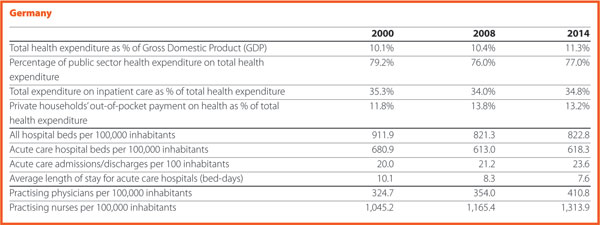

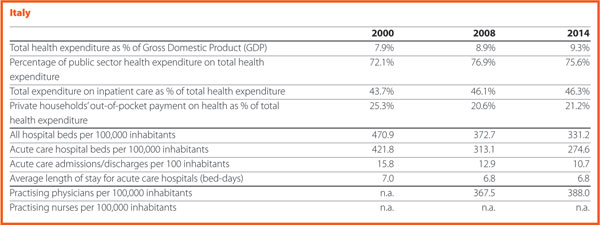

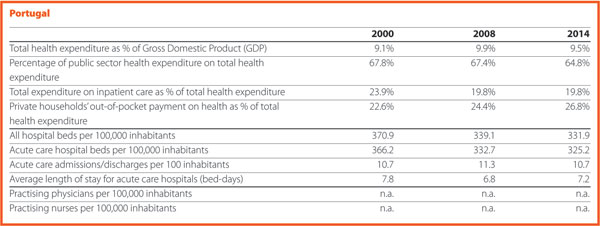

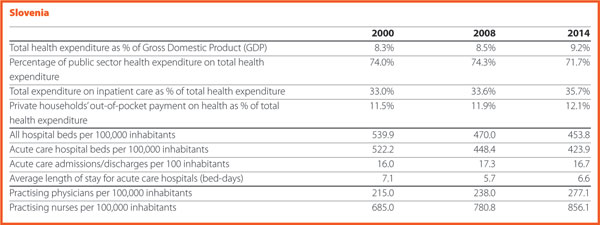

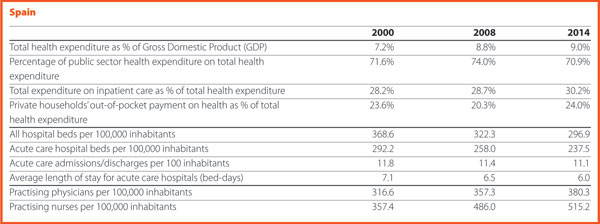

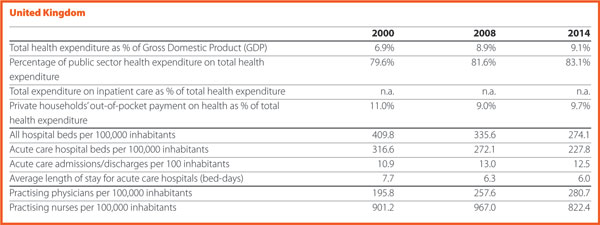

The figures given here provide the most up to date comparative picture of the situation of healthcare and hospitals, compared with the situation at the beginning of the 2000s. They aim to increase awareness on what has changed in hospital capacity and, more generally, in secondary care provision within European Union member states, generating questions, stimulating debate, and, in this way, fostering information exchange and knowledge sharing.

The sources of data and figures are the Health For All Database (WHO/Europe, European HFA-DB, February 20181) of the World Health Organisation and OECD Health Statistics (OECD.Stat, November 2017). All European Union member states belonging to OECD are considered, plus Switzerland and Serbia (as HOPE has members in both countries), when data are available. In the text, these are reported as EU. Whenever considered appropriate and/or possible two groups have been differentiated and compared: EU 15, for the countries that joined the EU before 2004 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom); and EU 13, for the countries that joined the EU after 2004 (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia). When averages on EU 28, EU 15 and EU 13 are reported, these generally refer to year 2014 and have been extracted by the Health For All Database. The considered trends normally refer to the years 2000–2015. When data on 2015 are not available, or they have not been gathered for a sufficient number of countries, the closest year is considered. Some figures are disputed for not being precise enough but at least they give a good indication of the diversity.

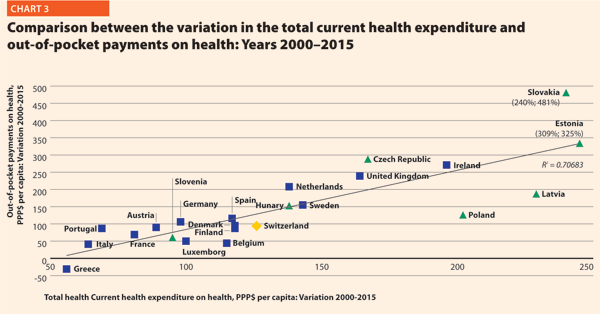

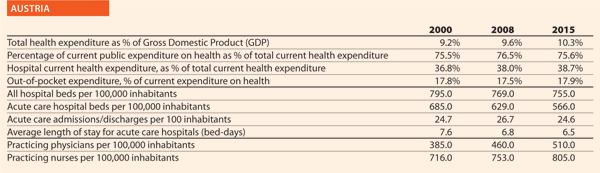

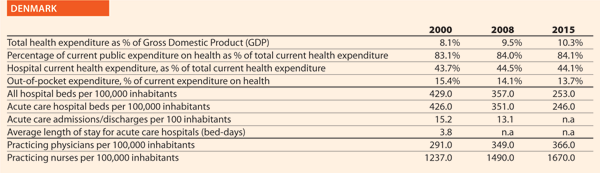

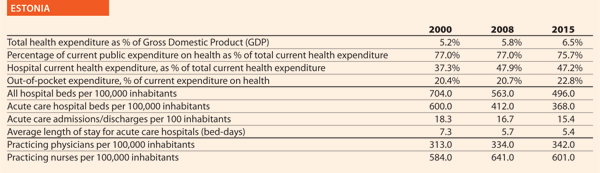

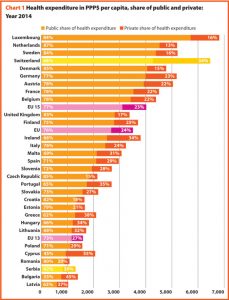

From 2000 to 2016, the total current health expenditure expressed in purchasing power parity (PPP$) per capita increased on average by 120% in the EU. Inpatient care, out-of-pocket payments and pharmaceutical expenditures, in particular, showed growing trends in the considered years.

In EU 15, the amount of total current health expenditure per capita in 2016 was encompassed between 2223 PPP$ in Greece and 7463 PPP$ in Luxembourg while in EU 13, this range varied from 1466 PPP$ in Latvia to 2835 PPP$ in Slovenia. In Switzerland, this indicator reached 7919 PPP$. Compared with 2000, the total health expenditure per capita in 2016 varied positively in all the countries taken into consideration in this analysis. Major increases have been registered in Ireland (+210%), Poland (+219%), Latvia (+236%), Slovakia (+257%) and Estonia (+309%).

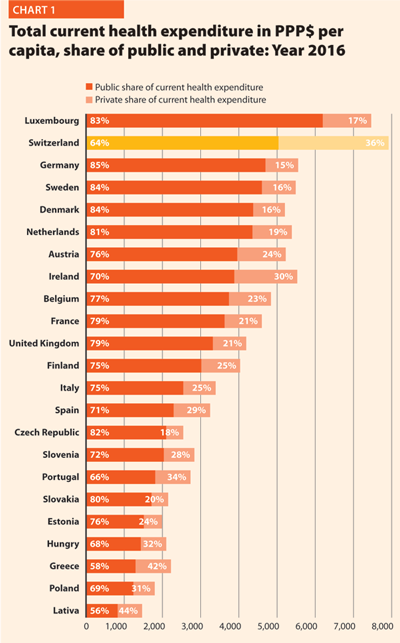

Public current health expenditure includes all schemes aimed at ensuring access to basic health care for the whole society, a large part of it, or at least some vulnerable groups. Included are: government schemes, social health insurance, compulsory private insurance and compulsory medical savings account. Private current health expenditure includes voluntary health care payment schemes and household out-of-pocket payments. The first component includes, in turn, all domestic pre-paid health care financing schemes under which the access to health services is at the discretion of private actors. The second component corresponds to direct payments for health care goods and services from the household primary income or savings: the payment is made by the user at the time of the purchase of goods or use of service.2

In 2016, the percentage of public sector health expenditure to the total current health expenditure was higher than 70% in most countries, except for Latvia (56%), Greece (58%), Portugal (66%), Hungary (68%) and Poland (69%) and outside the EU, in Switzerland (64%) (Chart 1).

Between 2000 and 2016, the public health expenditure in PPP$ per capita more than doubled in all the EU countries except in Greece (+49%), Portugal (+63%), Italy (+71%), France (+84%)and Austria (+84%). However, from 2008 to 2016, the variation was less significant than from 2000 to 2008.

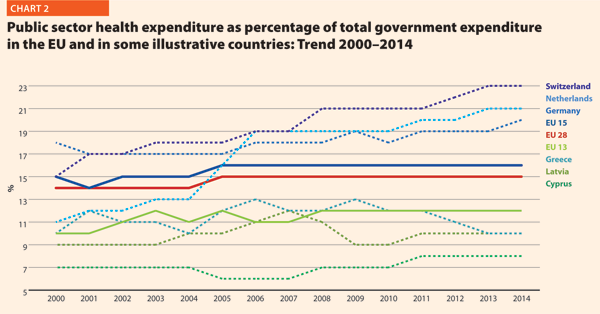

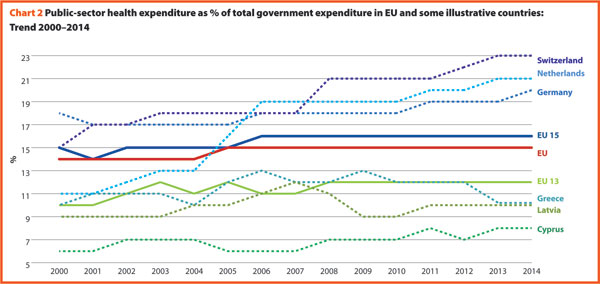

Chart 2 shows the last 14-year trend concerning the share of government expenditure in health. It presents the aggregated data concerning the EU, EU 15 and EU 13, and the figures of the three countries having the highest and the lowest values in the year 2014, Switzerland included.

In 2014, the percentages of government expenditure devoted to health differed by 4 percentage points (p.p.) between EU 15 (16.2%) and EU 13 (11.9%); Switzerland shows 22.7%, higher but also growing faster than the EU member states.

The trends illustrated in Chart 2 are generally positive between 2000 and 2006 with an average increase of percentage of government outlays devoted to health by 0.2 p.p. per year. Yet, from 2006 onwards, this way of development slackened off in many countries. The reasons can be the beginning of economic difficulties or in the shift of interest and priorities to other sectors.

Out-of-pocket payments show the direct burden of medical costs that households bear at the time of service use. Out-of-pocket payments play an important role in every health care system. In lower-income countries, out-of-pocket expenditure is often the main form of health care financing.3

In 2015, the private contribution to healthcare spending was around 20.0 % in the EU. It was higher than 25% in Portugal (27.7%), Switzerland (28.8%), Hungary (29.0%), Greece (35.5%) and Latvia (41.6%); it was lower than 10% only in France (6.8%).

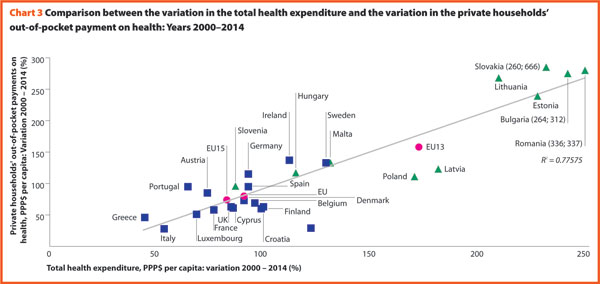

Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of out-of-pocket payments to total health expenditure steadily declined. In EU 15, reductions were registered in Finland (-3.3 p.p.), Luxembourg (-3.6 p.p.), Italy (-3.6 p.p.) and Belgium (-8.7 p.p.) while increases were observed in Portugal (+2.7 p.p.), Netherlands (+2.8 p.p.), Ireland (+3.0 p.p.) and the United Kingdom (+3.3 p.p.). In EU 13, according to available data, the abovementioned percentage increased in Hungary (+1.7 p.p.), Estonia (+2.4 p.p.), Czech Republic (+4.6 p.p.) and Slovakia (+7.6 p.p.) and decreased in Slovenia (-2.6 p.p.), Latvia (-6.0 p.p.) and Poland (-7.9 p.p.). The total out-of-pocket payments in PPP$ per capita continued to increase, because the total health expenditure did.

Chart 3 illustrates the trend 2000–2015 of both the total current health expenditure per capita and the private households’ out-of-pocket payments on health. These values present a correlation (R² = 0.7068) showing that there is dependence between the two indicators. The chart highlights the fast growth of both expenses in the countries located in the upper part of the graph. In the ones in the lowest-left part of the graph, the out-of-pocket payments grew more slowly compared with the total current health expenditure.

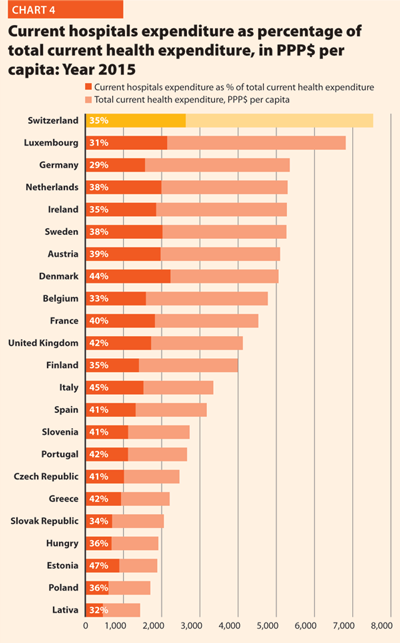

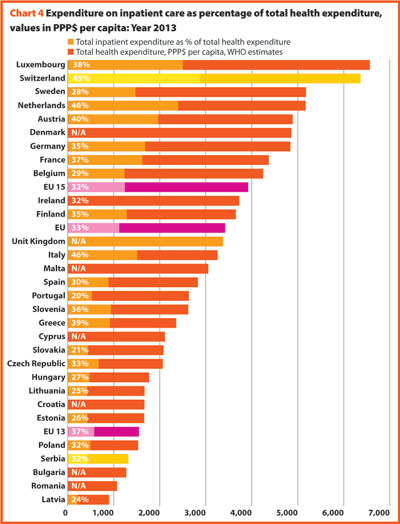

More than a third of current health expenditure (excluding investments and capital outlays) finances hospital care. The funds allocated to providers of long-term care, ancillary services, ambulatory care, preventive care, as well as to retailers and other providers of medical goods, are excluded from this computation.

In 2015, current hospital expenditure represented approximately 38.2% of total current health expenditure, ranging from 29.2% and 31.5% in Germany and Luxembourg, respectively, to 45.4% and 47.2% in Italy and Estonia (Chart 4). In all countries, even if a part of the total health expenditure is always funded by private insurances and out-of-pocket payments, almost the entire amount of inpatient health expenditure is publicly financed. The total expenditure on inpatient care (PPP$ per capita) in the EU follows, on average, a growing positive trend. The exception is Greece, where available data show that this indicator varies negatively (-23.0%).

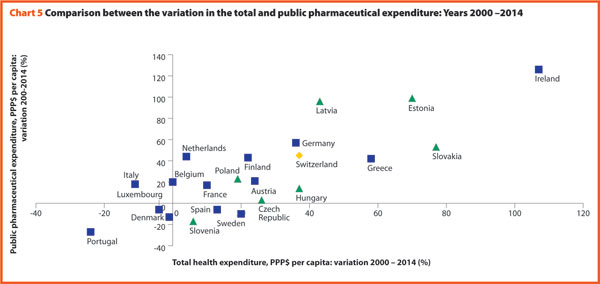

Pharmaceutical expenditure includes the consumption of prescribed medicines, over-the-counter and other medical non-durable goods. One of the indicators taken into consideration for 2015 was expenditure on pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durable goods, as percentage of current health expenditure. The countries that registered the lowest rates of this indicator are Denmark (6.8%), the Netherlands (7.9%), Luxembourg (8.6%) and Sweden (9.9%) while the highest one were Poland (21.0%), Greece (25.9%), Latvia (26.8%), Slovakia (26.9%), and Hungary (29.2%).

Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of pharmaceutical expenditure on total current health expenditure has generally declined in all of Europe. In 2015, the total pharmaceutical expenditure was between 342 PPP$ and 343 PPP$ per capita in Denmark and Estonia, respectively, and 766 PPP$ per capita in Germany. At least half of it was held by the public sector in all countries except Slovenia (49.5%), Denmark (43.7%), Latvia (35.0%) and Poland (34.1%). The highest values in 2015 were in Germany (82.9%), Luxembourg (80.2%), Ireland (74.6%), France (70.9%) and Slovakia (70.7%). In 2015, the pharmaceutical expenditure in PPP$ per capita held by the public sector was between 122 in Poland and 643 in Germany.

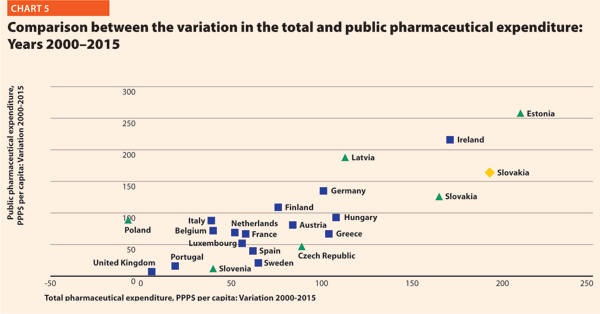

Chart 5 explores the relationship between the trend of the total and the public pharmaceutical expenditure between 2000 and 2015. In a group of outlier countries (upper right part of the chart) encompassing Estonia, Ireland, Switzerland and Slovakia, both the public and the total spending varies substantially. In Poland, the total pharmaceutical expenditure varies negatively.

In almost all EU member states, the total pharmaceutical expenditure decreased more slowly than the public pharmaceutical expenditure. This suggests that a progressively larger part of the total pharmaceutical expenditure pertains to the private sector. This shift may also indicate that the ‘willingness to pay’ and the consumption of pharmaceuticals by private owners are increasing.

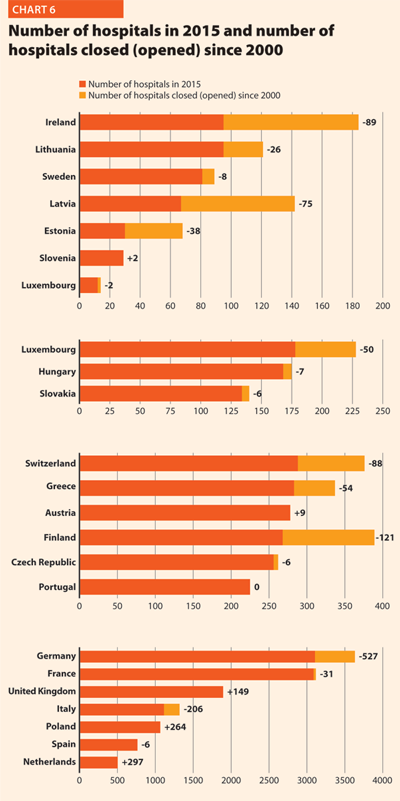

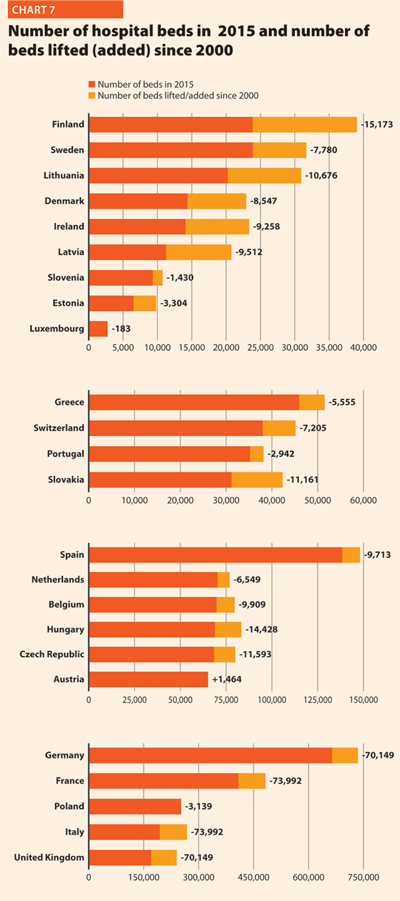

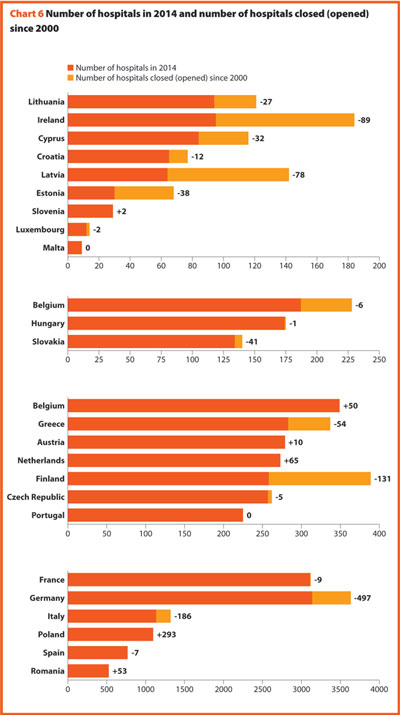

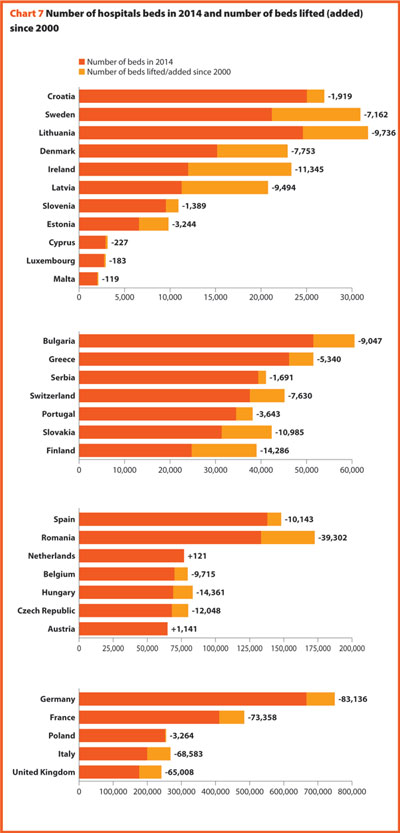

In the last 15 years health care reforms implemented all over Europe aimed at rationalising the use and provision of hospital care, improving its quality and appropriateness, and reducing its costs. The number of hospital facilities as well as the number of hospital beds dropped off on average (Charts 6 and 7). These reforms also resulted in a broad reduction of acute care admissions and length of stay, as well as in improvements in the occupancy rate of acute care beds.

During this time, almost all European countries made changes in their hospital provision patterns, and major efforts were addressed to delivering better services, increasing quality, improving efficiency and productivity. The streamlining of care delivery started from a sharp reduction in the size of secondary care institutions and moved towards more integrated and efficient patterns of care, which might result in the future in the complete overcoming of the hospital-centric model of care.

This was possible thanks to a package of financial and organisational measures addressed to improve coordination and integration between the different levels of care, increase the use of day-hospital and day-surgery and introduce new and more efficient methodologies of hospital financing in order to incentivise appropriateness (for example, the replacement of daily payments – known to encourage longer hospitalisation – by prospective payment).

In most European countries, these policies led to changes in the management of patients within hospitals and offered a possibility for reducing the number of acute care hospital beds. Only the bed occupancy rates registered more disparate trends across Europe, depending also on the demographic and epidemiological structure of population and the specific organisation of local, social and healthcare systems, that is, the structure of primary care, the presence and the efficiency of a gate-keeping system, the modality of access to secondary care, availability of home care and development of community care.

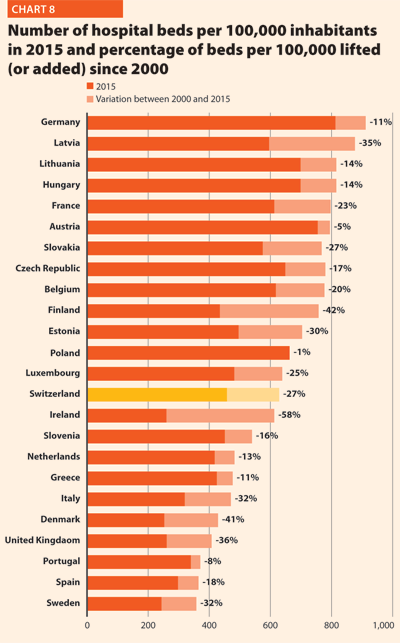

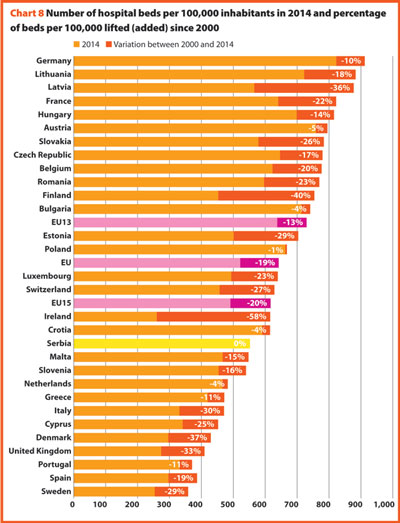

In 2015 there were, on average, 2.6 hospitals for 100,000 inhabitants, ranging from 0.9 in Sweden to 4.9 in Finland. The only European member state excluded from this range is Cyprus, where the value was approximately 9.9 in 2014. Moreover, there were on average 491 hospital beds every 100,000 inhabitants, ranging from 244 in Sweden to 813 in Germany.

Between 2000 and 2015 few changes in the number of hospitals were registered in Luxembourg (-2), Portugal (0) and Slovenia (+2).

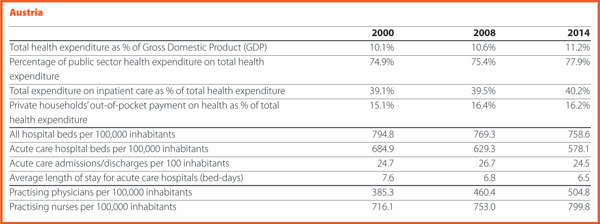

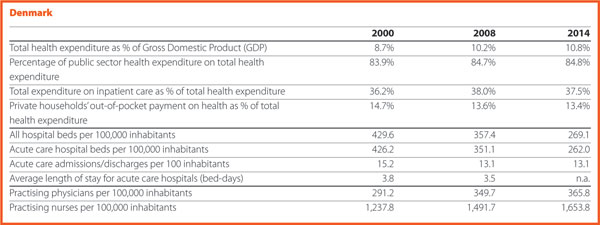

In the same period, the total number of hospital beds per 100,000 inhabitants decreased by 23.2%, ranging from -57.6% in Ireland (which means 353 beds cut for every 100,000 inhabitants) and -0.7% in Poland (5 beds cut for every 100,000 inhabitants) (Chart 8).

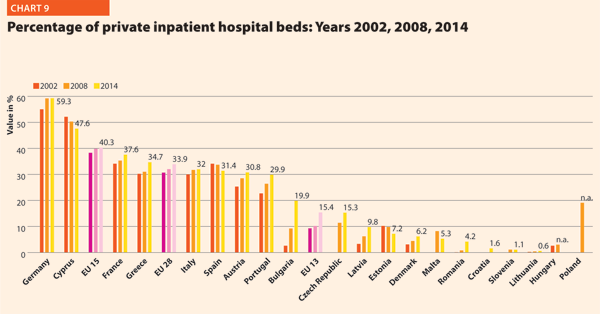

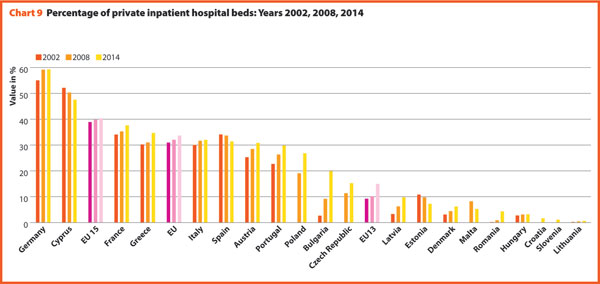

In several countries the decrease in the total number of beds was accompanied by a slight increase in the number of private inpatient beds, which are inpatient beds owned by not-for-profit and for-profit private institutions. But the share of private hospital beds – where figures are available – was still quite low in most countries, with percentages higher than 30% only in Spain (31.4%), Italy (32.0%), Greece (34.7%), France (37.7%), Cyprus (47.6%) and Germany (59.3%) (Chart 9).

Between 2000 and 2014, the number of acute hospitals decreased significantly all over Europe. A total of 357 acute care hospitals were closed in Germany, 193 in France, 170 in Italy and 122 in Switzerland.

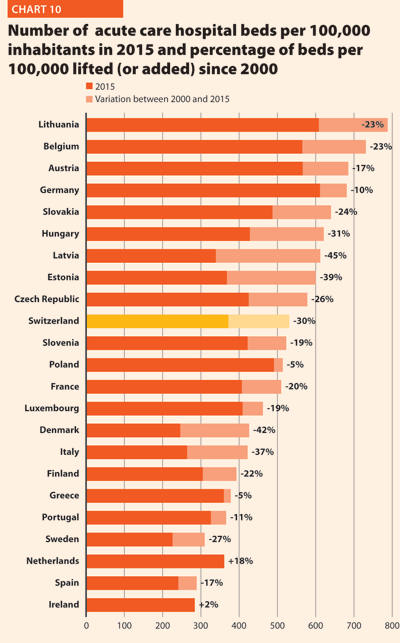

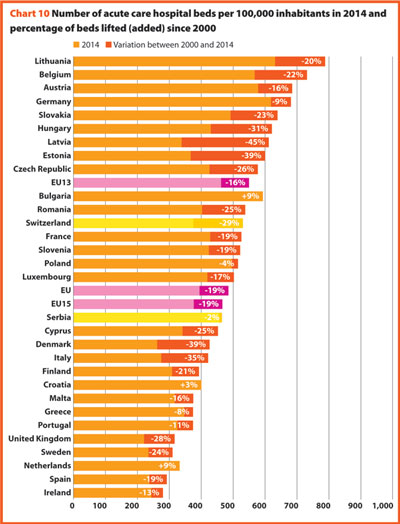

The rate of acute care hospital beds for 100,000 inhabitants in 2015 in EU ranged from 226 in Sweden to 611 in Germany. The highest figures were observable in Belgium (565), Austria (566) and Lithuania (608) while the lowest figures were in Spain (241), Denmark (246) and Italy (264).

Between 2000 and 2015, the number of acute care hospital beds per 100,000 population registered an average reduction of 20.5% in the EU. The most significant decreases were in Latvia (-44.6%), Denmark (-42.3%), Estonia (-38.7%) and Italy (-37.4%). The only exceptions were Ireland (+1.8%) and Netherlands (+18.4%) (Chart 10).

The reduction in the number of hospital beds regards especially the public providers. In the countries where data are available, this trend is associated with an increase of hospital beds in private structures. This is the case for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Latvia and Portugal. The countries that registered a decrease in both categories are the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Slovenia and Spain.

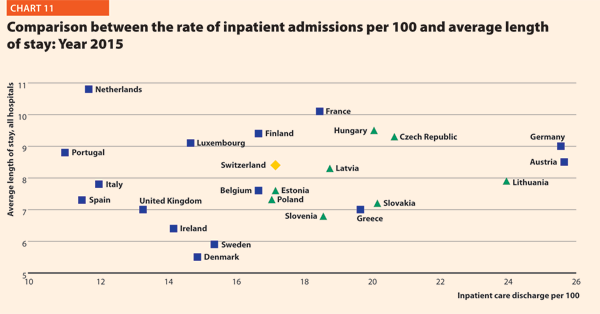

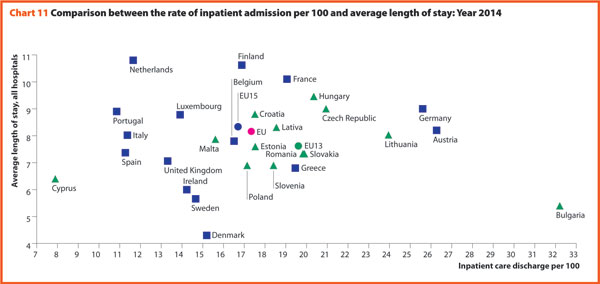

The number of acute care admissions involves the entire pathway of hospitalisation of a patient, who normally stays in hospital for at least 24 hours and then is discharged, returns home, is transferred to another facility or dies. Last data available for this figure is from 2014. The rates of acute care hospital admissions in the European countries were quite dissimilar, ranging from 7.8% in Cyprus to 24.6% in Austria.

The average length of stay measures the total number of occupied hospital bed-days, divided by the total number of admissions or discharges. In 2014, the average length of stay in acute care hospitals ranged from 5.2 bed-days in Malta to 7.6 bed-days in Germany. In Serbia, this value is 8.4 bed-days.

Between 2000 and 2015, almost all countries stabilised their rate of admissions for all hospitals. From 2000 to 2014, this figure decreased on average by 0.5 p.p. (from 17.8% to 17.3%). Most of them were also able to reduce the length of stay in acute care hospitals. Indeed, the EU average improved, decreasing from 7.6 bed-days in 2000 to 6.4 bed-days in 2014.

The link between the rate of admissions and the length of stay can be a very sensitive issue for hospitals, because it is commonly acknowledged that too short a length of stay may increase the risk of re-admissions, with a consequent waste of resources both for the hospital and for the patients and their careers. At the same time, staying too long in a hospital might indicate inappropriate settlements of patients, also causing a waste of resources.

Chart 11 compares the rate of hospital admissions and the average length of stay in 2015. The last updated data shows that the average European figures corresponds to a mean rate of admissions by 17.2% and a mean length of stay of 8.0 days for all hospitals. From 2000 to 2015, the foremost variations between countries concern the admissions, ranging from 10.9 in Portugal to 25.6 in Austria. A cluster of countries, mainly encompassing EU 13, presents a number of admissions per 100 higher than the EU average (17.2%). The smallest countries seem to be more successful in finding a good balance between these two indicators.

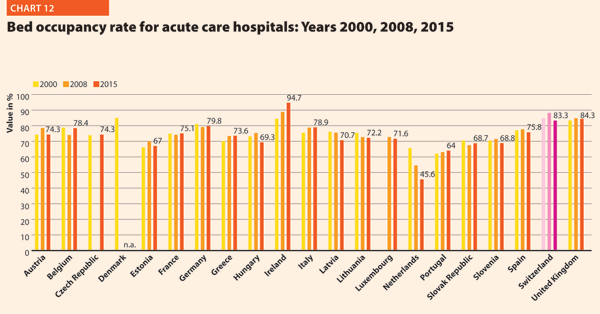

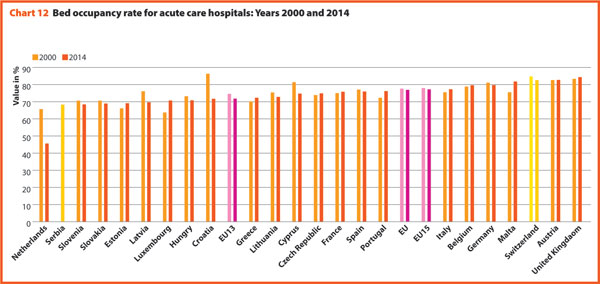

The bed occupancy rate represents the average number of days when hospital beds are occupied during the whole year and generally mirrors how intensively hospital capacity is used.

The average rate of acute bed occupancy decreased in Europe between 2000 and 2015. The reduction was between +3.4 p.p. in Greece and Italy and +0.1 in France and -5.4 and -0.4 in Latvia and Belgium. In the Netherlands, the decrease in p.p. was about 20.1. These large variations are usually due to changes in the number of admissions, average length of stay and the extent to which alternatives to full hospitalisation have been developed in each country.

In 2015, the share of employment in the human health and social work sector on total employment in EU was on average 10.0%. Unlike in the total economy, the number of workers in this sector had been steadily growing and showed an increase even during the crisis years. Furthermore, the health and social services sector, composed of human health, residential care and social work, has an important economic weight as it generates around 7.0% of the total economic output in the EU 28 and appears to have suffered from the crisis according to the European Commission supplement to the quarterly review on “Health and social services from an employment and economic perspective” (December 2014).

The review also underlines that the health and social services sector is facing several challenges due to the fact that the workforce is ageing faster than in other sectors. Indeed, the vast majority of the people working in human health and social sector belong to the age group 25–49 years, while the share of people above 50 years increased from approximately 27% to 32% between 2008 and 2013 in EU 28. Moreover, there are large imbalances in skills levels and working patterns and recruitment and retention are conditioned by demanding working conditions. The financial constraints in most European countries are leading to a decrease in the resources available for healthcare professionals, reducing the possibilities of hiring new staff. Additionally, several countries, especially in central and eastern Europe, are experiencing migrations of their healthcare workforce.

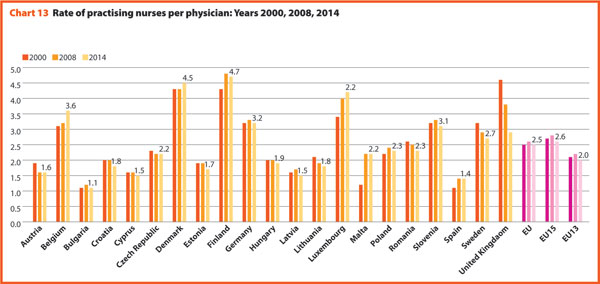

These trends are likely to have major impacts on the hospital sector, because inpatient care alone absorbs about a third of the healthcare resources and because the hospital sector gives work to more than half of active physicians. In 2014, the total hospital employment per 100,000 inhabitants was 1506 people in EU 28, whereas in EU 15 and EU 13, this value was 1589 and 988, respectively. European countries, European organisations and EU institutions are discussing possible impacts and achievable solutions to these issues. Interestingly, several countries are shifting competences from doctors to nurses, creating new educational pathways and bachelor degrees addressed to nurses. In many cases nurses and general practitioners acquire new skills and competencies, relieving the burden of hospital care by enforcing primary care institutions and community services.

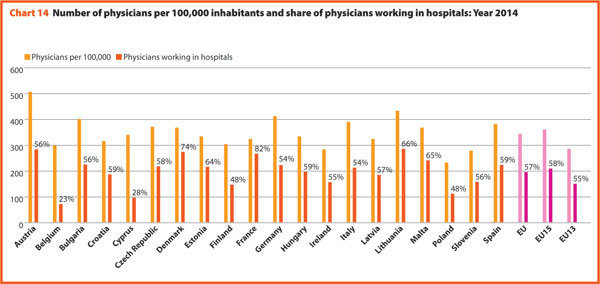

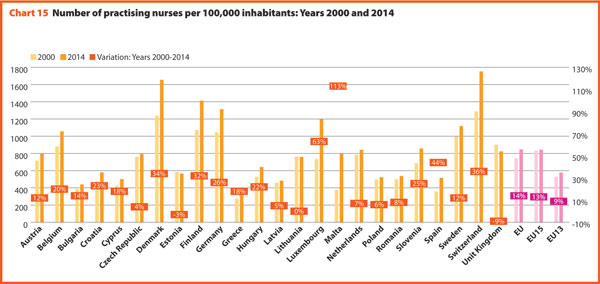

In 2014, EU15 had 359 practising physicians and 943 practising nurses per 100,000 inhabitants and EU13 had 284 physicians and 577 nurses per 100,000 inhabitants.

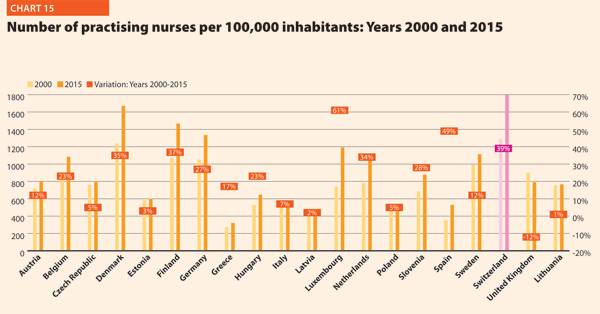

In 2015, the share of practising nurses per 100,000 registered the lowest values in Greece (321), Latvia (468), Poland (520), Spain (529) and Italy (544). The highest values belong to Germany (1,334), Finland (1,466), Denmark (1,670) and Switzerland (1,795). In the same year, the lowest share of practising physicians was registered in Poland (233), United Kingdom (279), Slovenia (283), Ireland (288), Luxembourg (291) whereas the highest values were in Germany (414), Sweden (419), Switzerland (420), Lithuania (434) and Austria (510). Between 2000 and 2015, the number of both practisng nurses and physicians increased by 20% in the EU, according to information available.

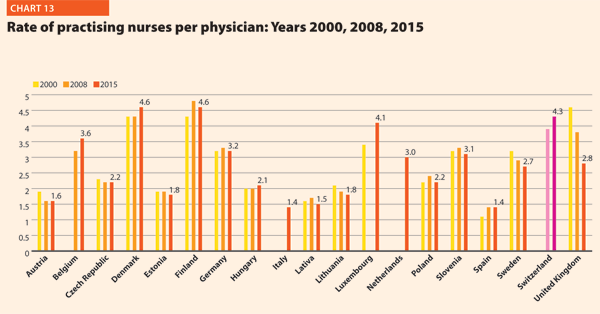

These figures provide evidence of the policies implemented, or at least the trends for the management of healthcare professionals, especially concerning the allocation of resources and responsibilities between doctors and nurses. In the EU, the average rate of nurses per physicians is about 2.1 points. In 2015 the highest values were in Luxembourg (4.1), Switzerland (4.3), Denmark (4.6) and Finland (4.6). In these countries, there is a high shift of competencies from physicians to nurses. Conversely, countries where the values are lower are Spain (1.4), Italy (1.4), Latvia (1.5) and Austria (1.6).

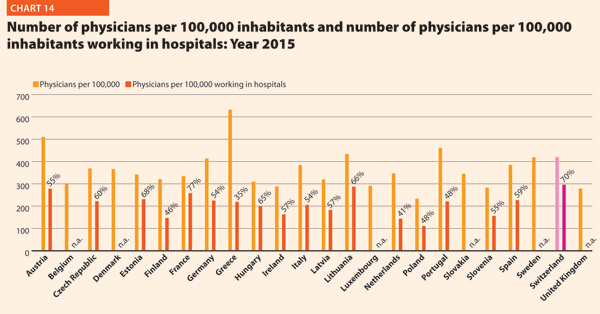

In 2015, physicians working in hospital (full or part time) were approximately 50–60% of the total, with the highest rates registered in Estonia (67.5%), Switzerland (70.5%) and France (77.2%). By contrast, the lowest values regard Greece (34.7%), the Netherlands (41.5%) and Finland (45.8%).

The most relevant positive variations on the number of physicians per 100,000 working in hospital between 2000 and 2015 were in Switzerland (+40%), Germany (+42%), Denmark (+43%) and Lithuania (+53%). By contrast, there were negative variations in Italy (-3%), Belgium (-2%) and Poland (-2%).

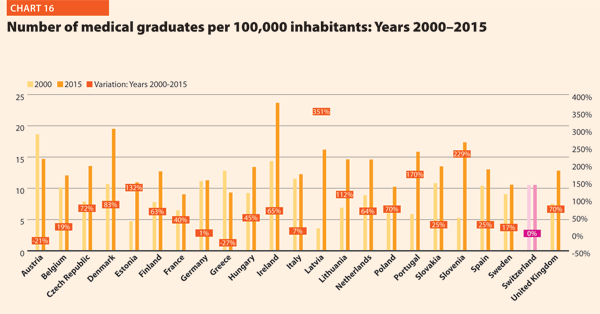

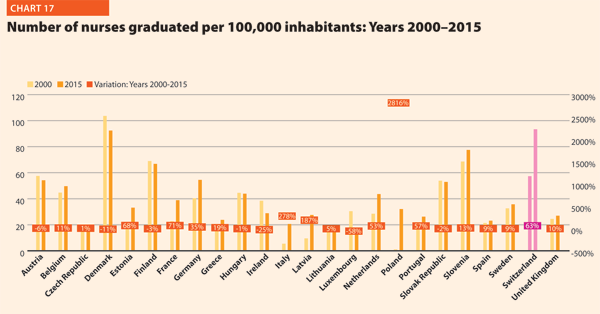

In 2015, the average number of medical and nurses graduates for every 100,000 inhabitants were respectively about 13.6 and 41.4 in the EU; however, the values across countries were quite different. The number of medical graduates per 100,000 inhabitants ranged from 9.0 and 9.3 in France and Greece to 19.5 and 23.7 in Denmark and Ireland. The number of nurses graduated per 100,000 inhabitants ranged from 12.8 and 15.8 in Luxembourg and the Czech Republic to 92.4 and 93.4 in Denmark and Switzerland.

Compared with 2000, the number of medical graduates per 100,000 inhabitants in EU registered a positive variation in the three Baltic countries (on average, around +200%), Portugal (+170%) and Slovenia (+229%). Conversely, according to data, the variation was negative in Austria (-21%) and Greece (-27%). The number of nurses graduated per 100,000 in the EU member states belonging to the OECD increased in Latvia (+187%) and Italy (+278%) and registered a remarkable positive variation in Poland (+2816%). The trend was negative in the years considered in Ireland (-25%) and Luxembourg (-58%).

The Federal Health Commission1 adopted the Austrian Quality Strategy in 2010, which was integrated by operational objectives in 2011 to be effectively implemented. In 2012, the Patient Safety Strategy became one of the most important issues of the Quality Strategy.

It aims at the continuous further development, improvement, and nationwide assurance of quality in the healthcare sector. It supports appropriate and, most notably, reliable healthcare services provision to the population. Quality shall become the guiding and controlling criterion for the Austrian healthcare system.

The strategic objectives are:

The strategic and operational objectives as well as the actions/measures based on them are checked regularly and if needed adjusted accordingly.

Additionally, the National Framework for Healthcare Planning (ÖSG-Österreichischer Strukturplan Gesundheit) was completely revised, extended, and then republished in Summer 2017. Constituent parts of the planning guidelines are standards on infrastructural quality of healthcare settings and establishments, such as the composition, qualification and attendance of treatment teams, (minimum) equipment standards, and the particular (minimum) range of services to be provided. These standards apply to selected therapeutic areas of in-patient and out-patient care. The applicable existing legal regulations were not far-reaching and detailed enough to ensure comprehensive infrastructural quality and allow regular control and comparability.

Patient orientation – in that patients shall be in the focus of the decisions and actions and are enabled to take an active part – is essential in making efforts to improve quality of care.

Active participation, however, requires a certain degree of personal competence and responsibility. Thus, in order to empower people to be actively involved, strengthening the health literacy of the population and vulnerable groups by appropriate measures is a declared common goal of the health reform partners over the next four years. The measures envisaged include the enhancement of independent information in the internet health portal (www.gesundheit.gv.at) on health and diseases as well as on possibilities of healthcare provision, available evidence of treatment options, and on the functioning of the healthcare system. Additionally, there will be standards developed on how written information on health issues can become most clearly understandable. In order to improve the oral communication between patients and healthcare providers and support both in being ‘partners’, healthcare providers will be trained to improve their communication skills.

It was also agreed to continue the regular cross-sector surveys on patient satisfaction with the service provision in the healthcare system.

The survey captures the patients’ experiences on care processes, in particular the communication and care processes at the interfaces. Data suggests that patients’ involvement in care processes may bring about an optimisation in the healthcare service provision. Surveys repeated on a regular basis allow for the monitoring of services and evaluation of improvement measures set. Patient experiences and opinions thus become the starting point for quality improvements and for the optimisation of patient pathways in the healthcare system.

Quality and patient safety are very important in the Danish Quality approach. Denmark established the National Quality Programme in 2016. It aims explicitly at building a nationwide improvement culture through eight national targets and a number of indicators, interdisciplinary collaborations and a national leadership programme. The approach is based on a close cooperation among the State, the regions and the municipalities. The goal is putting patients first and improving the results for them.

The programme replaced the accreditation in hospital and pre-hospital settings. Each hospital and region set their own goals in relation to the overall national targets based on the challenges they face. National learning initiatives and collaborations are established, with the aim of improving the clinical quality result in specific areas, and the experience for the patients and their relatives. In many ways, though, the work on quality was handed back to clinicians. This shall be interpreted as an act of confidence towards the health professionals and their inherent ambitions to improve clinical quality.

Improving the quality of healthcare using the experiences and competencies of patients is a central feature of the Danish approach. Patient safety is one of the eight national targets. Some examples of initiatives implemented in this regard are the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and of surveys on patient satisfaction covering many areas of the healthcare sector such as emergency care, psychiatry and maternity wards. Better continuity of care and improved patient involvement are two further national targets. “It is common understanding that the improvement of results for patients is the core of our daily activity. It is not as simple to accomplish it as it sounds, but the dedication is there. By keeping a close eye on the development within the targets we believe, we will come far along this new path”.

Estonia held its first term as the presidency of the Council of the EU from July to December 2017 during which the priority was to enhance cooperation on eHealth among member states and to reduce alcohol-related harm. The overall aim was to come to an agreement to reach Council conclusions to tackle these subjects.

Digital solutions provide people with better opportunities to take care of their health and help health professionals to improve the quality of treatment. Digital solutions allow patients to be more involved in decision making about their health and to make treatment more accurate and better tailored to individual needs. Citizens must have the right and opportunity to digitally access their health data, as well as to allow or restrain the safe sharing of health data for the use of various e-services.

“We have kept developing our eHealth systems during the last decade and we believe this has a huge impact on healthcare, including patient safety”.

The largest eHealth project is the introduction of the electronic health records system. This project aims to develop a basic infrastructure for the integration of healthcare providers’ data. The digital images, digital registration, and digital prescription projects use the same message administration, authorisation, central data storage, and other services created in the framework of the electronic health records project.

For a long time, Estonia has been tackling problems caused by alcohol consumption. The Estonian government has approved stricter alcohol policy and new laws to protect the country and, most importantly, the health of the youth by implementing restrictions on alcohol availability and its sale and advertisement. It has already changed people’s attitudes towards the display and availability of alcohol and made people seriously consider reducing their alcohol consumption.

Patient-centred care has been discussed and developed in different medical areas in Estonia for many years. Involving patients in their personal health development is a more successful way to achieve results than simply letting the doctor treat their disease. Patient centred healthcare improves the quality of treatment, has a positive effect on patient health and increases his/her satisfaction with treatment.

Patient-centred healthcare is the way to a fair and cost-effective healthcare system. Globally, health systems are under pressure and cannot be sustainable if they continue to focus on diseases rather than patients. They require the involvement of individual patients who adhere to their treatments, make behavioural changes and self-management. Patient-centred healthcare may be the most cost-effective way to improve health outcomes for patients.

To make this happen, all stakeholders in the healthcare field, including the patient, must change their attitudes and behavioural patterns. The patient takes responsibility for self-educating about different treatment options, participates in choices and follows the agreed treatment, changing the attitudes and behaviour accordingly.

The Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs started a Patient Safety Development Initiative, dealing with the main issues related to patient safety, the green paper on quality and the Patient Insurance Act. Currently this act is in the development phase. The aim is to reduce the risk of doctors’ fear of potential legal liability to a minimum, which would enable them to focus more on patients’ effective medical treatment.

According to the Healthcare Act (No. 1326/2010), Section 8 on quality and patient safety, the provision of healthcare services shall be evidence-based. The healthcare services provided shall comply with the highest quality standards and be properly organised. Each healthcare unit shall produce a plan for quality management and for ensuring patient safety. The plan shall include arrangements for improving patient safety in cooperation with social services. The issues to be covered in the plan are laid down by decree of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

The Patient Safety Strategy has been released for the years 2017–2021. It will help to develop a cohesive safety culture.

Disease-specific quality registers are patients’ groups or disease-specific care monitoring systems that support the daily care of patients. They gather structured clinical data that can be used for monitoring the effectiveness and quality of treatments. Disease-specific quality registers are being used to monitor 52 disease groups.

A register for 27 additional groups of diseases is under development.

HaiPro is a web-based tool for reporting patient safety incidents. It is used by over 200 social service and healthcare organisations of various sizes: from small healthcare centres to entire hospital districts. The HaiPro reporting system supports the development of procedures within the organisation.

The Healthcare and Social Services Act, stating the division of activities among hospitals, emergency services, first aid and emergency social services has been reformed in 2018. The objective is to guarantee equal access to services, sufficient skills and knowledge, patient safety and to decrease health expenditure.

The Health and Social Services Act reforming process is ongoing.

In Finland, the patient orientation is highlighted in healthcare planning, implementation and evaluation. Patients have been involved as experts in government working groups. The development of healthcare and social welfare provision will be based on patients’ experiences and participation.

One of the government key projects is the establishment of a model based on expert’s experience and patient involvement. In Central Finland Healthcare District, forms of co-design have been developed in specialised medical care, primary healthcare, social welfare and municipal welfare work. The aim is to increase patient and citizen participation in planning, preparation and evaluation of healthcare services by collecting feedback on their experience. A model of co-design for patient-driven self-management of non-communicable diseases was developed. Observations based on expert experience in psychiatric departments were provided in 2017.

In Satakunta Hospital District, a patient panel participated in the planning and construction of a new hospital. The panel gathers patients’ feedbacks to develop services and products and to create or test new ideas.

One of the government key projects is the development of virtual hospital services. Finnish university hospitals are building a joint national virtual hospital, which, in practical terms, means a digital service hub for specialist healthcare. It aims to develop patient-oriented digital healthcare services for citizens, patients and professionals.

The project, which runs from 2016 to 2018, is a joint initiative coordinated by the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District HUS. In developing digital healthcare services, the patients and their needs define the core of the service and the value chain that is built around it. In the Virtual Hospital 2.0 project, the patient’s voice has been affirmed in such a way that the current e-service development model brings patients, their close friends and patients’ organisations into service planning and design.

Inclusion methods are based on patients’ interviews, service design workshops, participation at working groups, and patient relationship management. The service design also includes experienced experts, peer educators, and specialist patients’ organisations.

For the last ten years, the High Health Authority (Haute Autorité de Santé – HAS), has been producing guidelines on a number of topics, in collaboration with learned societies. Furthermore, every hospital has to be evaluated and certified by HAS regarding safety and quality. Efforts have been made to introduce patient centric procedures, that led in turn to a decrease of severe adverse events. Patient satisfaction is measured by the hospital

and contributes to a better fit between patient expectations and medical procedures.

Simultaneously, the Health Ministry and the French National Sickness Fund put in place policies and programmes aimed at reducing the number of unnecessary medical procedures, most notably through monetary penalties. An atlas on variation of medical practices has been produced, focusing on nine procedures. It shows huge geographical variations, pushing hospitals and providers to search for explanations of these variations.

Enhanced recovery programmes are identified as a major axis of development of oncology in France. Therefore, many French comprehensive cancer centres have now implemented, or are about to implement, those programmes to meet cancer patients’ wishes to safely go home shortly after surgery. The programmes, coordinated by a healthcare professional, cover the patient pathway and provide different measures, such as:

Eight French comprehensive cancer centres have been labelled as reference centres by the Francophone Group of Improved Rehabilitation After Surgery (Groupe francophone de Réhabilitation Améliorée Après Chirurgie – GRACE).

Despite the efforts of the Health Ministry, Sickness Fund and HAS, in the implementation of programmes relying on penalties, success remains somewhat limited, in large part because of a lack of appropriation by front-line clinicians. The approach adopted is ‘top-down’.

Since 2015, the French Hospitals’ Federation (FHF) is part of ‘Choosing Wisely’, an international campaign launched in the US and Canada, which aims to improve the dialogue between patients and clinicians on the topic of relevance. Since 2017, the FHF is the national leader for this campaign. Learned societies as well as patient associations have since then started working on ‘Top 5’ lists.

A national logo has been created, and the construction of a website is under way. The lists will be displayed on the website and will be accessible by providers and patients alike.

One of the first of these lists, concerning geriatrics, has been tested in all of the hospitals of the Region of Brittany, and three of the five items have shown their relevance and robustness. Work has been undertaken to improve the quality of recommendations and their understanding by patients. The FHF provides technical support in the process and helps to create consensus regarding the items that will constitute the Top 5 lists.

A national advertising campaign will be launched in hospitals as well as in non-hospital settings in GP’s offices. Around 20 learned societies are already part of the campaign.

The FHF is also working with the Deans of Medical schools to introduce ‘Choosing Wisely’ in the medicine curriculum, as well as to organise activities around this theme involving French and foreign students.

In 2017, UNICANCER launched a project that aims to facilitate the communication between cancer patients and their healthcare professionals. The idea of the initiative is to set up a digital tool, collecting data on the patient experience on consultations during their treatment for cancer. The survey has met with good success, from the perspective of both patients and doctors, allowing the patient experience to be brought to light to help medical decisions. The project will be extended to further comprehensive cancer centres that volunteer to participate.

German hospitals are continuously working on improving quality of care and patient safety. They actively apply CIRS – Critical Incident Reporting System (sharing evaluated experiences with colleagues and other hospitals) at hospital wards, at local, regional and national level and support the National Action Alliance on Patient Safety (campaigning for safety issues, for example, hand hygiene).

Additionally, several legal initiatives have been implemented. Hospitals are assessed annually on approximately 400 quality indicators by an external institute and receive a report that has to be published. The data of this so-called ‘system of external quality assurance’ serve as a basis for the official hospital directory and search engine for patients, and encourages doctors to provide a very high level of transparency and quality. The IQTIG (Institute on Quality and Transparency in Healthcare) will soon provide an objective quality criterion for ‘pay for performance’ and for hospital planning. Minimum volumes for provision of healthcare services are defined and minimum numbers of staff for intensive care services are defined. Finally, hospitals provide comprehensive discharge management services to their patients.

Hospitals are conducting voluntary patient surveys aimed at collecting feedback on their experience concerning all aspects of their stay (for example, personal satisfaction with admission procedures, information and communication by the hospital, accommodation, quality of the staff or of the catering, waiting times and hygiene).

In certain circumstances, these interviews are also addressed to the relatives and partners of patients. Some of these surveys are also used for benchmarking. In addition to this voluntary assessment of patient satisfaction, hospitals are asked to question patients on different services by the Federal Joint Committee as part of the mandatory quality assurance system on the basis of an interview form developed by the IQTIG.

German hospitals also have patient advocates who assist patients in representing their interests. Acting independently in the hospital they moderate between healthcare providers and patients. As this option was given by law, some Federal States have already developed recommendations for them, providing both framework and contents for their duties and rights. Additionally, hospitals have for some time also applied complaint management systems. They provide options for patients to complain anonymously about all aspects of their treatment. This feedback delivers valuable information for hospitals on how to improve services.

The aim of old quality assurance systems was to regulate the healthcare processes, which would have led, in turn, to better results in the future. The new approach shifted the focus to the final result instead: patient safety. This means that all healthcare processes have to be planned and structured in the light of all potential risks that can pose a threat to the patients, starting from the purchase of healthcare materials. This challenge is addressed by the new ISO 9001:2015 standard.

The majority of Hungarian hospitals operate by ISO-certified quality assurance systems. However, with the use of EU resources, the Hungarian Government managed to set up a customised standard framework (called BELLA) in 2014, which is in line with the international quality requirements (ISQua) and focuses on patient safety.

The Hungarian Hospital Association supports the new quality assurance methods. Hospitals are applying indicators which are suitable for monitoring patient safety and its shortcomings, partly following-up on own data and comparative analysis based on information gained from other similar institutions. The main points of the new system are continuous learning and self-assessment which is, of course, challenged by an external review once a year. The process of accreditation is being elaborated at the time of writing (January 2018) and will be ratified. An online tool (NEVES) is maintained for reporting all unexpected (adverse) events.

In-patients participate in a pre-organised and personalised counselling session before they leave the hospital. The person who is responsible for this tailored service has to be sure that the patient has understood all the advices regarding healthy living, physical exercise, physiotherapy, diet, and use of medical devices. Patients are free to ask questions. Healthcare providers have to certify all these aspects in the final report. Hospitals operate a well organised system for the management of patients’ complaints and comments.

Several staff members are involved in the investigation of complaints. However, it is the managing director who makes the decision. There are independent patients’ rights commissioners in each hospital, representing patients’ interests in problematic cases and supervising the fairness of the investigations. The leadership looks into all the complaints annually and suggests development measures when needed. Hospitals run their own web pages, which aim to provide information but also work to receive information and feedback from the patients.

Quality and patient safety are prominent issues of the Italian health policy. National legislation states that patient safety is in itself a part of the right to health. Promoting quality means to promote a multi-sectoral strategy, involving staff, patients, strengthening a safety-culture which would be incorporated in each health organisation. Many actions addressing towards this direction, are stated by Italian National Law for monitoring sentinel and adverse events, supporting risk management, promoting training and education for staff and education for patients.

With regards to monitoring, since 2009, National law states that hospitals and healthcare trusts have to monitor sentinel events, transmitting specific reports to the National Health Ministry.

Another important initiative, the National Outcome Evaluation Programme, started in 2011, has been promoted by Agenas (National Agency for Regional Health Services). Agenas collects records from hospital trusts and health local trusts and calculates specific indicators of quality, such as the percentage of femur neck fractures being treated by surgery within two days, and the percentage of AMI being treated by PTCA within two days.

The aim is monitoring quality of care by means of indicators coming from a routine database so that this monitoring has to be incorporated in the control system of each health organisation, on a regular basis.

Regarding a multi-sectoral approach, the most advanced experience is the Pilot Project CARMINA, started in 2010 and supported by the National Health Ministry. It is based on a self-assessment questionnaire aimed at evaluating the level of patient safety of an organisation. Each health organisation is tested through 52 items covering the following main areas: safety culture, communication, human resources, safe environment and safe contests, care processes, management of adverse events, and management of health records.

Using patients’ experiences and competencies along with other components such as effectiveness and safety of care are essential for providing a complete picture of healthcare quality. This is helpful to get a better patient compliance in the treatment: listening to patient experience is important for providing an effective and anticipatory guidance to establish a health maintenance and management plan to promote health and to prevent potential problems.

This means, also, that the patients (or designee) are recognised as a source of control and a full partner for providing compassionate and coordinated care based on patient values, needs and preferences. Moreover, it is important considering several aspects of healthcare service provision that patients value highly such as: getting timely appointments; providing easy access to information; providing good communication between staff, patients and care-givers.

In Italy, patients’ representatives are involved in many working groups and/or projects such as pain free projects, specific disease projects (for example, diabetes treatment), health promotion projects and waiting list working groups. The aim is to create an appropriate health culture, which is very important considering the potential overexposure of patients to health information that is often fake news.

Over the last ten years, the strategy adopted by the Ministry of Health in Portugal included several structural initiatives:

The Ministry of Health, through the annual reports of the Safety and Quality Committees, monitors the development of quality and patient safety activities in the national healthcare institutions. These are: national guidelines adopted and audits performed in the institution; certification of healthcare units and institutions; safety culture assessment; communication safety; surgical safety; safe use of medicines; identification of patients; notification and risk management; prevention and control of infections and antimicrobial resistance.

The main expectations on improving the quality of healthcare using the experiences and competencies of patients are:

Approximately 15 years ago, the Ministry of Health introduced the programme of quality improvement in the health sector. For that purpose, the Department for Quality was established. First, a set of quality indicators was developed with the cooperation of the Institute for Public Health of the Republic of Slovenia and the hospitals themselves. Hospitals were obliged to collect data and to report indicators to the Ministry of Health. In this period, the ‘non-blame culture’ was developed in hospitals. Moreover, the quality indicators were published and made available on hospitals yearly reports. Finally, the Ministry published each year a brochure with indicators for all hospitals.

In 2012, the Ministry of Health and the Health Insurance Institute of Slovenia agreed that hospitals should have been accredited by an international accreditation model by the end of 2014. For hospitals not accredited by that date, it was decided that the price for services would have been decreased for 0.3%. Hospitals were allowed to choose the accreditation model by themselves. Most of them decided for DNV-GL accreditation, the other decided for JCI. Since 2016, this obligation does not now exist. Some hospitals still have their accreditation model established and others have decided to use ISO 9001 and ISO EN 15224. Health institutions are still facing some blame from media and the general public for the adverse events reported.

In 2017 Ministry of Health initiated the so-called Šilih project. The main purposes are to identify and validate measures to reduce and prevent warnings and adverse events during medical treatments; to exercise the right to adequate, high-quality, and an effective judicial procedure when mistakes occur.

In Slovenia there is a big gap between expectations of the population regarding healthcare services and the possibility of public financing to assure those services. The results of this gap are very long waiting lists and waiting times for specific services. Emergency care is provided immediately. For all elective services, regardless if they are needed with urgency, the providers (hospitals) cannot assure them in reasonable time. Spine surgery represents one of this cases. Waiting time for service differs among hospitals and varies from six months to more than two years. It is a reasonable expectation of patients and healthcare providers that government should address its resources (financial and human) to decrease waiting times. Since public opinion is that providers are responsible for waiting times regardless of the fact that these are actually caused by a lack of resources, hospitals also expect that Government would accept the responsibility. The other expectation of the providers is to start to rebuild a ‘non-blame culture’ because the trust between patients and providers is at its lowest-ever level and consequently it is very hard for healthcare professionals to work in such circumstances.

In the past in the University Medical Centre of Ljubljana, there was a board of patients nominated to improve the management of processes, taking into consideration their experiences. This is a good example of patient empowerment.

The Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality (MSSSI) fosters and promotes the Patient Safety Strategy for the National Health System, which has been carried out since 2005 in collaboration with the Health Regions and the National Institute of Health Management (Instituto Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria – INGESA), integrating the contributions of the healthcare professionals and of the patients through organisations representing them.

The objectives of this strategy aimed initially at: promoting and enhancing patient safety culture in the healthcare organisations; incorporating risk management practices; training the professionals and patients on basic aspects of patient safety; implementing safe practices and getting patients and citizens actively involved.

The Patient Safety Strategy has been extended for further five years (2015–2020) to provide an overview of what has previously been done and to facilitate decision making based on consensus. Furthermore, the strategy has been evaluated positively showing that the established collaboration with the Health Regions has worked efficiently. The contributions of the professionals and their organisations turned out to be crucial and the scientific societies have played a key role. Finally, the patients and their representatives contributed to patient empowerment.

The update presented herein incorporates the strategic actions set out, including the international recommendations and the achievements and objectives defined on the base of available evidence. The team that contributed to shape the strategy is composed of scientific and technical coordinators and the institutional technical committee of the Health Regions.

This network provides patients, family members and care-givers with a source of information and training services, giving them access to the best scientific evidence available. It is based on the contributions of various schools and projects within the National Health Service (Escuela Andaluza de Pacientes, Escuela Cántabra de Salud, Escuela Gallega de Salud para Ciudadanos, Programa Paciente Expert Catalunya, Programa Paziente Bizia Osakidetza) along with the Citizen Training Network of the National Health System, the Ministry and the Foundation of Health and Ageing of Autonomous University of Barcelona (Fundacio Salui i Envelliment – Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona – UAB). It also receives contributions from patient and professional associations.

The European Council and the WHO World Alliance for Patient Safety stress the importance of the engagement of patients and their relatives in the improvement of healthcare safety. Many initiatives have been studied to support patient engagement and to face this challenge. Nevertheless, the role of patient as auditor of safety practices remains almost unexplored. It consists of voluntarily and anonymously tracking clinical practices.

Some of the suitable practices in which to engage the patient as auditor are those that require an external observer (hand hygiene, patient identification, transfusion, chemotherapy administration, etc.). The adherence to those safety practices cannot be measured by analysing data gathered through the information system. For example, it is possible to detect a wound infection but not if the healthcare professional washed his/her hands before or after the contact with the patient.

The role of patient as auditor does not imply that he/she has to take an active role reminding the healthcare professional to follow a safety practice (for example, the patient reminding the nurse or doctor to wash their hands if they did not).

It requires the patient to assess if the professional follows the procedures in normal conditions.

To explore the feasibility and validity of patient participation as partner in the audit of safe practices, the Navarra Complex Hospital (Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra) is performing an innovative project composed of several stages. They are developing some learning materials while evaluating the feasibility and validity of the patient as auditor. Furthermore, they are exploring the experiences and perceptions of patients, professionals and managers about the role of patients as safe practices auditors.

One important initiative on quality in the healthcare sector was the annual open regional comparisons of healthcare quality and efficiency, that the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and SALAR started to publish annually in 2006. SALAR now provides such statistics online at vardenisiffror.se.

The purpose was to make the publicly financed healthcare system more transparent, promote healthcare management and control, and to contribute to improved data quality and simplified data access. The comparisons are based on several different indicators reflecting various dimensions of quality and efficiency such as medical outcomes, availability, patient experience and costs. Different sources are used, like the national healthcare quality registries and population/patient surveys.

Comparisons have changed the perspectives, by giving attention to differences in medical results and outcomes, and revealing regional differences concerning quality of care. Now the debate is not just on compliance to budget, but also to a larger extent on quality issues.