This website is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Take a look at a selection of our recent media coverage:

28th April 2023

The Flemish Institute for Quality of Care (VIKZ) is a network organisation that measures, follows up and publicly reports on healthcare quality indicators and safety to drive quality improvements.

In this webinar, Svin Deneckere, Director of VIKZ, focuses on quality indicators and public reporting in Flanders. He presents the organisation’s methodologies, preliminary results and future objectives.

HOPE and HealthPros have been collaborating with researchers from the Amsterdam University Medical Centres at the University of Amsterdam since 2020 around the subject of data sharing and exchange.

This webinar presents the results of the project. There is special emphasis on examples of how data exchange between hospitals and other healthcare organisations changed during the Covid-19 pandemic in different member states across Europe.

The Dutch Hospital Patient Safety Program started in 2008. It initially ran for five years, and its aim was to decrease adverse events by 50% in all Dutch hospitals.

A second National Safety Program launched in 2020. This focuses on reflection, interprofessional collaboration and explaining process variation in daily practice. It also looks to foster more patient involvement and shared decision making. The ultimate aim is to reach a significant reduction in preventable patient harm.

This webinar provides an overview of patient safety in the Netherlands and discusses these two initiatives and their implementation, outcomes and ongoing impact.

Management of Belgium’s healthcare system is complex, with federal financing and regional regulation and strategy for areas such as patient safety improvement.

The development of a Regional Strategy for Patient Safety Improvement involved two surveys. The first looked at system-level, organisational and clinical-level interventions and resulted in a list of top priorities.

PAQS released a second survey at the end of 2018. It asked healthcare professionals to consider the current situation and how it could be improved.

This webinar discusses healthcare in Belgium and analyses the survey results and the development of the regional strategy.

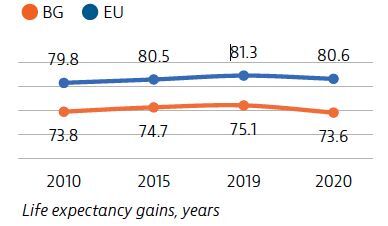

The Covid-19 pandemic has temporarily reversed years of progress in life expectancy for people in Bulgaria, for whom life expectancy was already the lowest in the EU in 2019.

Despite health system improvements over the last decade, the impact of persistently high risk factors, high out-of-pocket payments and excessively hospital-centred care continue to hamper the system’s performance.

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the need for additional investment in the health sector, including better preparedness for future health system shocks. For Bulgaria, this challenge also includes investment to create a uniform health information system to speed up the use of e-health and to ensure appropriate working conditions for the health workforce.

Overall life expectancy at birth in Bulgaria temporarily fell by 1.5 years in 2020 compared to 2019, largely due to the high number of deaths from the Covid-19 pandemic. Stroke, ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer are the leading causes of death and accounted for one third of all deaths in 2018.

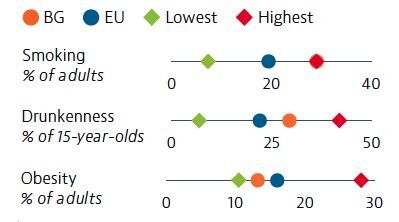

Smoking, unhealthy diets, alcohol consumption and low physical activity are responsible for nearly half of all deaths in Bulgaria. The adult and adolescent smoking rates are the highest in the EU. Alcohol consumption among adolescents is also a concern. In contrast, obesity among adults is below the EU average.

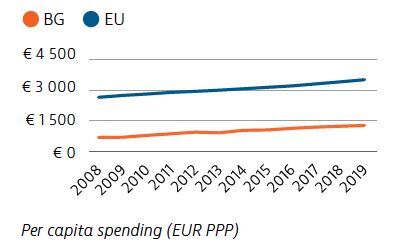

Bulgaria’s health expenditure per capita has doubled overall since 2005. However, it remains much lower than that of the EU as a whole, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP. Public financing of the health system accounted for 61% of health spending in 2019. Out-of-pocket spending (38%), driven mainly by costs for outpatient pharmaceuticals, was more than 2.5-times the EU average.

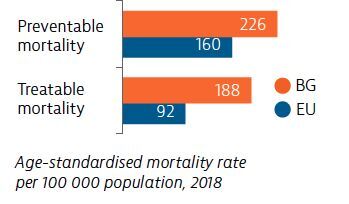

Deaths from both preventable and treatable causes are well above the rates for the EU as a whole, reflecting weak primary prevention and health promotion activities, as well as the need to improve diagnosis and treatment protocols for leading causes of death. Survival rates for the most prevalent cancers are among the lowest in the EU.

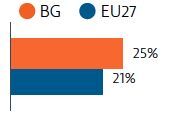

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Bulgaria’s rate of self-reported unmet medical needs had declined to reach just below the EU’s average. However, during the first 12 months of the pandemic, nearly 25% of the population reported having to forgo care compared with 21% in the EU27. Out-of-pocket spending levels, insurance coverage gaps, referral quotas and uneven distribution of medical personnel and equipment across the country remain challenges to access.

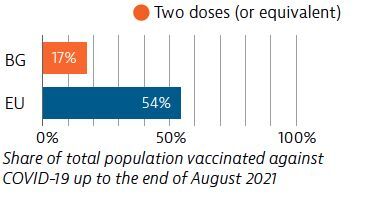

Bulgaria had enough intensive care unit and acute bed capacity to treat Covid-19 cases when the hospital system came under strain. The rollout of Bulgaria’s Covid-19 vaccination campaign has been slow and, as of the end of August 2021, only 17% of the population had received two doses (or equivalent).

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Bulgaria: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

20th April 2023

In Germany, hospital risk management is organised around cross-institutional critical incident reporting systems based on a legal framework to increase joint learning and improve patient safety.

This webinar outlines this legal framework, discusses the results of related projects and provides an example of such a system used for national, interprofessional and interdisciplinary learning: Krankenhaus-CIRS-Netz Deutschland 2.0.

17th April 2023

Dr Andrew Coats describes himself as a career cardiologist specialising in heart failure. He is CEO and scientific director of the Heart Research Institute in Sydney, Australia.

Spending around two-thirds of his time in Australia and the remainder in the UK, Dr Coats has had three separate careers. He left medicine to pursue several management and fund-raising roles, took up an academic position and finally moved into commercialisation – currently holding many patents and three start-up companies focusing on devices related to heart failure.

He spoke to Hospital Healthcare Europe about his career and work in cardiology.

The Institute is dedicated to heart disease and is a basic science research institute looking at novel treatments. In addition to running the Institute, I still find time to see patients, where my focus is on heart failure. The centre is involved with the delivery of a wide range of cardiovascular treatments and interventions, including transplantations.

The challenge in healthcare is getting funding for ever more that you can do. Running a clinical service in the NHS, as I did in the early 2000s, brings its own challenges, especially managing performance, but having an MBA management qualification helps a lot. While most managers look for ways to increase staff performance, in the NHS setting I had to manage performance differently. Given a fixed annual budget for the services we could provide, my role was to prevent surgeons and cardiologists from undertaking too much work and spending the fixed annual budget too quickly. But managing a service is difficult with the overarching challenge being to make it all work under cost pressures, disease pressures, surviving the Covid-19 era, dealing with political diktats and doing it all affordably, despite the demand from an ageing population and expectations increasing.

While there are many clinical and scientific achievements within the organisation, the people are both our best weapon and our worst enemy. Consequently, it is fundamental to achieve a sense of team spirit, effective leadership and communication – you can do 10 times more if you align people and if they’re working together. You can have people who are working furiously for what they perceive as the important pressures and what they’re trying to achieve, but a lot of that effort is wasted if they’re not co-ordinated. The biggest challenges and the greatest successes are achieving a joined-up sense of working together.

It’s not so much the written strategy for an organisation that is ultimately important but the process of writing one because you get people to talk to each other and understand each other’s perspective. This creates a shared understanding of what they are trying to achieve together and not just their piece of the puzzle. This shared understanding is crucial to the success of a service, largely because it allows clinicians, whose primary focus is patient care, to appreciate the wider perspective of the service as a whole.

The Institute has formalised and written curricula, which are accredited, for young doctors wishing to specialise in cardiology. These doctors are allocated to hospitals with dedicated trainers and educators to allow them the necessary time to gain experience and become independent consultants a few years later. Over the last 10 to 15 years, there has been a greater and separate accreditation for their ability to perform certain complex or high-risk procedures. This requires the clinician to demonstrate capability, audit their practice and do a minimum number of procedures every year to maintain their accreditation.

Today, I’m a clinical researcher who evaluates patients rather than undertaking laboratory-based work. In other words, assessing patients’ responses to treatment or the impact of novel devices and involvement with clinical trials. I’ve been involved in many studies over the years and some have led to changes in clinical practice. For instance, I was the first to demonstrate the huge benefits of exercise among those with end-stage heart failure awaiting a transplant, dispelling the perceived wisdom at the time that such patients should not exercise. While not the only group, my team and I were able to show that beta-blockers – which were thought to worsen heart failure and should therefore be avoided – could in fact improve survival if started slowly. More recently, I’ve worked with others to discover that the SGLT-2 inhibitors designed for use in type 2 diabetes are effective in heart failure.

While there have been many benefits associated with medical treatments, devices are very much a growth area. This includes several device therapies that, for instance, can cause electrical stimulation and blockade of the reflex control system, as well as those pacing the heart in a more sophisticated way. Or even devices to control blood flow across the chambers of the heart. Such devices, together with stem cell and gene therapy and monoclonal antibodies, mean the developments in heart failure occur from a variety of different sources.

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges in cardiovascular disease is the need for a paradigm shift in the treatment approach. There are currently two diametrically opposed approaches: splitters and lumpers. The splitters’ philosophy is predicated on the belief that because every patient is unique, treatment should be personalised. In contrast, lumpers believe it is more productive to focus on a particular disease and perform trials to see what works. However, while the lumper approach identifies benefits for patients with a particular condition, these interventions are not always 100% effective.

In heart failure, for example, there are actually two types: a low and a high ejection fraction. Drug treatments mainly work in low ejection fraction. In fact, when drug therapy was used in those with a high ejection fraction, the treatment was ineffective simply because there are several possible causes of this type of heart failure. In trying to better understand which patients are likely to respond to a treatment intervention, cardiologists have borrowed the strategy of precision medicine used by oncologists.

It therefore becomes possible to define patients into much smaller subtypes of disease and then optimise the treatments for this subgroup. While patient identification may initially be more expensive, the overall cost to the health service is lower as there are a smaller number of patients within each subtype. In short, the challenge is therefore to move cardiology from lumpers to splitters and develop more precision medicine.

I’m also involved in multiple research projects developing a raft of innovations, and these will hopefully deliver improvements to the care of patients with heart failure in the coming years.

Dr Coats is an advisory board member for HHE Clinical Excellence in Cardiovascular Care. He will be chairing a panel discussion at the event on 10 May 2023. Find out more and register for free here.

6th April 2023

In support of our mission to provide high-quality clinical education, Hospital Healthcare Europe is proud to announce a new series of events in 2023: the HHE Clinical Excellence programme.

Kicking off with cardiology and developed in conjunction with an expert advisory board of renowned key opinion and thought leaders from UK Centres of Excellence, our first one-day event on 10 May 2023 will allow you to explore the latest advances and innovations in cardiovascular care.

The event is free to attend and comprises individual presentations, panel discussions and sponsored sessions delivered virtually live and on-demand, all tailored to provide maximum convenience and work around your busy schedule.

Why should you attend?

What’s on the agenda?

How do you attend?

Tickets to attend the HHE Clinical Excellence events are free. Book them here. Tickets allow virtual access to all the talks throughout the day. And if you miss any of the sessions, catch up on-demand at a time to suit your schedule!

Save the date! And register to join us on 10 May 2023!

25th February 2023

The use of automated dispensing cabinets for controlled drugs on hospital wards has had proven benefits on patient care and medication safety. Can these benefits be replicated in a hospital pharmacy?

Controlled drug medicines must be stored securely and their use requires chronological detailed records in a controlled drug register.1,2 Challenges with management of controlled drugs in a hospital pharmacy include time-intensive mandatory record keeping processes and physical reconciliation of stock, often further compounded by inadequate storage facilities and capacity.

UK hospital pharmacies have sought to increase the use of robotics, and while there are limited published data on quantitative outcomes, the consensus is that they have provided benefits through a reduction in dispensing errors and improvements in dispensing efficiency.3,4 However, robotics systems have not been used for controlled drugs due to difficulties in complying with legislative storage and record keeping requirements, thus leaving controlled drugs to be managed through traditional lock and key cupboards and paper ledgers for documentation.

Automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) utilise technology to increase efficiencies and effectiveness on hospital wards and reduce the rate and risk of adverse drug events.5,6 ADCs have been widely implemented in UK hospital wards but not in pharmacies. ADCs are computerised storage cabinets, which integrate with hospital systems, utilising biometric technology eliminating the requirements for keys. Configuration of the ADC allows separation of medicines that look alike and sound alike, thus minimising the risk of medication selection errors.

There is extensive literature on medication errors, defined as any preventable event that may lead to an inappropriate medication use or patient harm.7 The use of automated systems has improved the processes for using medication safely. The Institute for Safe Medicines Practice has stated that the automation of medicines management processes is a high-powered risk minimisation strategy in enhancing medication safety.8 There are many reports on the benefits of ADCs in ward settings and their impact on reducing medicine administration errors, omission of medicines and medicine storage errors in addition to increasing resource management efficiency.7,9

However, there is little information in the literature on using automated dispensing systems for the management of controlled drugs in a pharmacy setting.

Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (BHSCT) is the largest health and social care trust in the UK. It provides the majority of regional specialist services and its hospitals are the major teaching and training hospitals for Northern Ireland. Within the Royal Victoria Hospital pharmacy department, controlled drug medicines were stored in a small controlled drug strong room on open shelving in alphabetical order. Over 80 paper controlled drug registers were in use at any time. There had been a 20% increase in controlled drug dispensing activity in the five-year period from 2013 to 2018. Additionally, the Carter Report recommended that hospital pharmacies should have a 15-day stock holding of medicines.10 This placed an enormous pressure on storage capacity and adversely affected working conditions within the strong room. The high volume of work processed led to an increase in errors including medicine mis-selection, documentation and stock control all of which contributed to heightened staff anxieties when assigned to controlled drug tasks.

The project sought to establish if an ADC in the pharmacy could improve medicines safety, release efficiencies and improve the experience of staff delivering the service. This was the first time an ADC had been installed in a pharmacy in Northern Ireland.

A number of baseline measurements of controlled drug activities were completed to define the aims of the project. Observation of workflow patterns revealed that in addition to core dispensing and supply activities, a significant amount of time each day was required by staff to verify and correct controlled drug registers. These observations led to the development of a driver diagram (Figure 1).

The project hypothesis was that the installation of an ADC would see a reduction in controlled drug errors along with a decrease in dispensing times, which would be achieved by reconfiguring process steps. The dispensary manager and controlled drug technicians took part in a focus group workshop to scope and design new workflows using an ADC. The workshop was crucial to the success of the project and ensured that the core dispensary team were engaged with the improvement process. An intensive training plan was developed; key personnel were nominated as super-users and received additional specific training commensurate with that role. The project team were mindful that change management was critical to obtaining a successful outcome and that challenges with a project such as this may be behavioural rather than technical.12 In total, 131 staff had received training on the ADC by the time of project Go-Live.

A seven-cell Omnicell automated dispensing cabinet was installed in the pharmacy department in November 2019.

In the pre-ADC period, dispensing data were collated at various times over a two-week period; the data included controlled drug items dispensed to replenish ward stock, and controlled drug items required for patients’ discharge prescriptions. The sample size of 66 items was equivalent to approximately 20% of the weekly controlled drug dispensing workload. Analysis of the dispensing process revealed there were five core steps in the preparation of a controlled drug item:

The average time to dispense a controlled drug medicine was 6 minutes and 18 seconds.

There are two distinct dispensing processes for controlled drugs within the pharmacy: items required for ward stock replenishment (typical supply is an original pack); and supply for discharge prescriptions, which must be the exact quantity for seven days as per regional policy.

The average length of time to dispense an original pack of a controlled drug for ward stock was 5 minutes and 47 seconds. The average length of time to dispense a 7-day supply of a controlled drug was 8 minutes and 12 seconds due the additional steps of packing down into individually labelled containers.

Analysis of the individual dispensing steps found that 43% of the total time was required to complete the controlled drug register entry and verify stock balance.

Three weeks after implementation of the ADC, dispensing data were collated for 76 items over a two-week period, equivalent to approximately 25% of the weekly workload. To replicate the pre-ADC data collection, a similar proportion of ward stock and prescription items dispensed was observed.

The number of discrete steps in the dispensing process had reduced from five to four. That is:

The impact on dispensing process times was immediate, with the average time taken to dispense a controlled drug item of 2 minutes and 41 seconds (a reduction of 57%).

The average time required to dispense a controlled drug for ward stock was 2 minutes and 8 seconds, which is a 63% reduction in dispensing time. The time taken to dispense a discharge item was on average of 3 minutes and 35 seconds, a reduction of 56%.

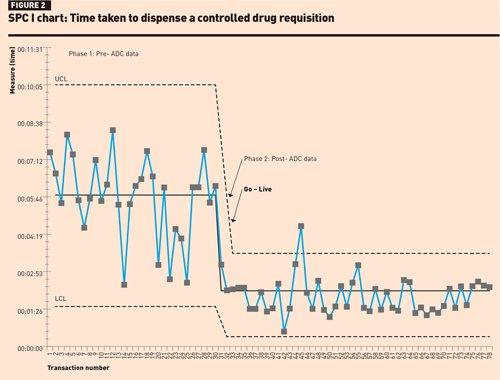

The SPC I-chart for dispensing a ward stock item (Figure 2) shows a level of instability and variation in dispensing times in phase 1; however, no rules for special cause variation were observed. In phase 2, there was one data point above the upper control limit, which could have been operator-related, possibly attributed to using the new system. There were 15 consecutive data points close to the centre line suggesting that the improvement in the mean dispensing times was not by chance.

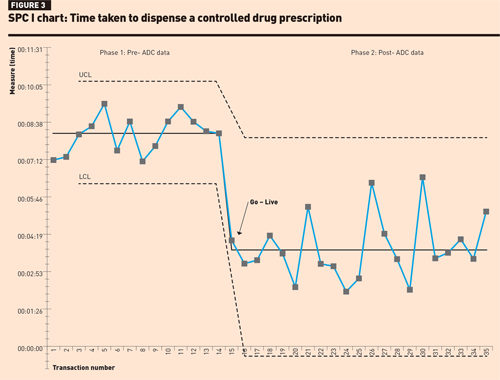

Review of the SPC I-chart for prescription dispensing times (Figure 3) found that in phase 1, although dispensing times were longer there was less variability between data points. In phase 2, although the mean dispensing time had reduced, none of the rules for special cause variation could be applied, possibly due to the smaller sample size.

A Mann–Whitney test was performed on the dispensing times and resulted in a p-value <0.00001, suggesting that the elimination of the paper controlled drug register is significant in terms of efficiency gains.

Further analysis of the dispensing steps using the ADC found on average 36 seconds per transaction was saved during the selection and assembly phase.This can be attributed to ADC technology, which uses a series of guiding lights to direct the dispenser to the required bin location.

The primary objective of this project was medication safety and therefore patient safety; the layout of the ADC was enhanced to optimise risk minimisation strategies, this included configuring all controlled drug items to individual bins or zones. The RVH Pharmacy ADC system was the first in the UK to implement this design approach.

In the three-week period prior to installation of the ADC, an error-recording log was designed to record controlled drug-related errors including documentation, issuing or selection errors. An error rate of 24 errors per 1000 items dispensed was calculated; analysis of the errors recorded found that 82% were attributed to documentation, subtraction errors in running balance or omitted entries. It took 135 minutes to correct the documentation errors.

In the three-week period immediately following implementation of the ADC, the electronic controlled drug register was reviewed and an error rate of 9 errors per 1000 items dispensed was calculated. The errors recorded were categorised as operational, for example, wrong quantity selected on pharmacy dispensing system or counting errors. These errors were communicated to the team and operating protocols were revised to ensure staff were clear on management of procedural issues. The interface between the pharmacy dispensing system and electronic controlled drug register eliminated previously noted documentation errors.

The BHSCT extended hours seven-day pharmacy service is delivered by the RVH Pharmacy department with staff from four pharmacy departments contributing to the weekend and evening rotas. Prior to the implementation of the ADC staff reported that controlled drug tasks were difficult and stressful particularly at weekends. Contributing factors were a high volume workload, and range and complexity of controlled drug dispensing, which led to documentation and discrepancy errors. There was staff dissatisfaction with the manual dispensing process and recognition of the potential risk of picking the wrong injection, including incorrect ampoule size or strength. All of these factors influenced the department’s ability to achieve key performance targets for dispensing times.

Following implementation of the ADC, staff reported liking the layout of the cabinet, noting it was easy to use and felt safer as every item had a specific location within the cabinet. There was huge satisfaction that paper registers were no longer required. Staff perceptions were that the ADC enables them to perform their duties more safely; this is reflected in similar studies among staff using an ADC at ward level.13 The implementation of the ADC and associated workflow helps staff to complete dispensing processes accurately and safely eliminate documentation errors.

Implementation of a large-scale automation project such as this requires significant financial investment. Efficiencies achieved from streamlining the dispensing processes and utilising an electronic controlled drug register has a wider impact on patient care. The improved turnaround times for dispensing stock requisitions reduces the risk of omitted doses of critical medicines at ward level. Prescriptions are dispensed more efficiently ensuring the successful discharge of patients, which, in turn, helps the smooth admission of the next patient.

Approximately 1200 controlled drug items are dispensed each month in RVH Pharmacy; thus the ADC is contributing to dispensing time savings of 67.3 hours per month, an equivalent of 808 hours per year. Utilisation of this resource will allow the release of staff to other duties including patient facing roles.

This project has demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of an ADC in managing controlled drugs in a hospital pharmacy. A training programme will be developed for junior staff who would not have previously undertaken controlled drug duties to build contingency and stability into the pharmacy workforce.

Future developments will focus on linking ward-based ADCs with the pharmacy ADC to further enhance the efficiency of controlled drug workflow between ward and pharmacy. BHSCT plans to install controlled drug ADCs in all its hospital pharmacies.

Aideen O’Kane MPharm MSc MPSNI

Warren Francis MAT (Member Association of Pharmacy Technicians)

Conor Duffy BSc

John Mullan BSc MSc MPSNI

Rhona Fair BSc MSc PGDip MPSNI

Lucy Smart MPharm MPSNI

Aoife Ramsey MPharm MPSNI

Pharmacy Department, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Belfast

We thank L McKee and T Cameron for participating in the focus group for controlled drugs workflow.

First published by our sister publication Hospital Pharmacy Europe.

A retrospective study undertaken in a UK hospital to investigate adherence to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) criteria and guidance in treatment of atopic dermatitis with a biologic therapy is detailed

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, recurrently flaring, generalised skin condition that can be life-limiting, debilitating and isolating. It can affect all aspects of life (physical, psychological, social and financial). Severe disease is associated with intolerable itch that disrupts sleep, and there is a higher risk of depression and suicide.1 It affects 2%–10% of adults worldwide and can be associated with other systemic disorders such as asthma.2

The severity of atopic dermatitis and its effect on quality of life is assessed by a variety of scoring systems that include both subjective and objective measurements.3 A typical treatment pathway involves emollients and topical corticosteroids (first line), topical calcineurin inhibitors (i.e., tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) as second line, phototherapy (third line) and systemic immunosuppressant therapies (fourth line) including oral corticosteroids, ciclosporin (the only licensed drug), methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Long term use of systemic agents is not recommended due to the risk of adverse side effects.4

Dupilumab was the first therapy to be approved for moderate-to-severe AD that does not respond to topical therapies based on large, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials.5–7 Dupilumab (Dupixent, Sanofi Genzyme) is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the signalling mechanisms of cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13. It is indicated for the ‘treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy’. It is given by subcutaneous injection and the recommended dose is 300mg every two weeks after an initial loading dose of 600 mg (two 300mg injections at different sites). Various national guidelines position dupilumab either after other systemic therapies6 or as another systemic therapy option in the pathway for uncontrolled atopic dermatitis.7–9

Across England and Wales, guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) assesses the clinical and cost effectiveness of health technologies, including pharmaceuticals. The National Health Service (NHS) is legally obliged to fund and resource medicines and treatments recommended by NICE’s technology appraisals (TA). Furthermore, the NHS Constitution, which sets out rights to which patients, public and staff are entitled, and pledges which the NHS is committed to achieve, states that patients have the right to drugs and treatments that have been recommended by NICE for use in the NHS, if their doctor believes they are clinically appropriate.8

Within the NICE TA, dupilumab is recommended as an option for treating moderate to severe AD in adults, only if: the disease has not responded to at least one other systemic therapy, such as ciclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, or these are contraindicated or not tolerated; and the company provides dupilumab according to the commercial arrangement. Dupilumab should be stopped at 16 weeks if the AD has not responded adequately. An adequate response is: at least a 50% reduction in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score from when treatment started; and at least a 4-point reduction in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) from when treatment started.1

EASI assesses both lesional intensity and extent. Four signs – erythema, papulation/oedema, excoriation, and lichenification – are assessed using a scale of 0 to 3. EASI assesses the average lesional intensity within four body regions:

Lesional extent is evaluated by estimating the surface area involved of those four body regions (1%–9%, 10%–29%, 30%–49%, 50%–69%, 70%–89%, and 90%–100%). Lesional intensity is multiplied by the surface area involved in that region and summed across regions, yielding a total score ranging from

0 to 72.9 DLQI consists of 10 queries that assess the patient’s perception of the effects of the specific skin condition on their health-related quality of life over the past week. Summing the score of each question resulting in a maximum of 30 and a minimum of 0. The higher the score, the more quality of life is impaired.10

The NHS price for dupilumab excluding VAT is £1,264.89 for 2x300mg, although a patient access scheme is in place as part of the NICE TA. A patient access scheme or commercial arrangement associated with the NICE guidance is a way for pharmaceutical companies to lower the acquisition cost to the NHS to improve its cost-effectiveness, so enabling patients to gain access to high-cost medicine treatments. High-cost medicines are so named as they are expensive prescribed items, representing a disproportionate cost relative to the total NHS cost of the relevant hospital episode in terms of volume and cost.

The hospital

Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust is a 750-bed acute teaching district general hospital in the south-west of England. The hospital, in conjunction with the local clinical commissioning group (CCG, now integrated care board), utilises the Blueteq high-cost drug management system. CCGs were statutory regional NHS bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of healthcare services for their local area. Many CCGs in England use this Blueteq web-based system which allows clinicians to complete an online proforma for patients prescribed a high-cost medicine and receive automatic approval for funding if the patient meets all the relevant criteria which normally reflect the NICE TA guidance. This ensure that clinicians receive the approval to treat immediately. The Blueteq system retains, as an audit trail, the request history, including patient name, drug, indication, criteria for use, date of request, requesting clinician, and whether the request was granted or not. This enables commissioners to monitor the use of expensive treatment, so that only treatments prescribed in line with NICE guidelines are reimbursed to the hospital.

Aim

We aimed to identify whether dupilumab had been used according to the criteria based on the NICE TA.

Methods

This was a retrospective, single site study in an acute teaching district general hospital. An extract was downloaded from the Blueteq system for adult patients granted approval to commence dupilumab treatment for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, and who were then potentially eligible to receive such treatment for more than 16 weeks. Relevant data (patient demographics and treatment details) were imported into Excel by a member of the pharmacy team. Dermatology correspondence (as part of the medical record) were examined as far back as 2012 if necessary for relevant information about patients’ treatment.

Health Research Authority criteria about research and service evaluation were considered. This was a retrospective assessment involving no changes to the service delivered to patients, and we used the NHS Health research authority tool (www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/index.html) which helped confirm that no ethical approval was required for this project. Patient data were used in accordance with local NHS hospital policy.

Results

At the time of the Blueteq extract, there were 88 patients on the Blueteq system, and the records of 30 patients were reviewed. Most entries were from when the NICE TA first approved dupilumab, though a few entries were chosen from late 2021/early 2022

There were 18 males and 12 females who had commenced on dupilumab and been reviewed approximately 16 weeks later; mean age was 44 years (range 18–73).

Twenty-six (87%) patients had tried phototherapy and 26 (87%) had evidence in their dermatology records of having been prescribed a course of prednisolone at some point. As regards the named prior systemic therapy (ciclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate) in the NICE TA, all but one patient had been on at least one of these medicines. Four patients had tried all four therapies.

One patient, who began dupilumab at a tertiary centre, did not have a starting EASI score in our hospital records. Of the 29 patients with a baseline score, 28 (97%) experienced the required 50% or more reduction in EASI score at the review meeting, whilst 28 (93%) of all 30 patients achieved the at least 4-point reduction in DLQI. One patient did not meet both NICE criteria showing only a reduction in EASI score from 33.6 to 27.9 (and not the required 50% reduction) and DLQI from 30 to 28 (and not the 4-point reduction) , and one patient had the required reduction in EASI score from 48 to 2 but did not have the required DLQI reduction (only a decrease from 13 to 10 and not the 4-point reduction ). Both had their treatment ceased. Table 1 shows overall results at baseline and at review.

Discussion

This small-scale study found that 28 of 30 patients met all the NICE starting requirements for dupilumab treatment. The two instances of non-compliance were one patient who did not have recorded locally an EASI score, and one patient who did not try any prior systemic therapy. This latter patient, whilst waiting for an appointment to commence ciclosporin, was admitted acutely to hospital with severe atopic dermatitis and started on dupilumab as this was deemed to be quicker acting with no need to wait for the necessary blood tests associated with immunosuppressive therapy.

Two patients who did not meet the reduction in EASI or in DLQI at review both had their treatment ceased. The drug cost impact of continuing inappropriate treatment in these two patients would be about £33,000 per year at NHS price and excluding VAT as these are provided via homecare. The actual cost impact is less than this due to the commercial arrangement in place.

A similar UK based study reported on 30 patients who received dupilumab after one or more immunosuppressive drugs.11 Their patients had average scores of 30 on EASI and 15 on the DLQI at baseline (compared to our study values of 29.7 and 18.9, respectively). All their 30 patients showed adequate response at 16 weeks and therefore continued to receive dupilumab. They report a mean 70% reduction in EASI after 16 weeks, and a 4-point or more reduction in DLQI for all the 30 patients. Of our 29 patients with a baseline EASI score, we saw at least a 70% reduction in 26 patients, with a further 2 patients achieving the NICE requirement of at least a 50% reduction and the one patient who did not achieve this reduction had therapy stopped. Two of our 30 patients did not meet the required DLQI score reduction. The patient who did not achieve the DLQI reduction had severe side effects from dupilumab and this would have adversely influenced the DLQI score. This patient with a poor DLQI response moved onto baricitinib as another option approved by NICE.12

The reported results from our small study are not directly comparable with the major controlled trials for dupilumab which enrolled different groups of patients. SOLO1 and SOLO2 enrolled adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis whose disease was inadequately controlled by topical treatment.5 LIBERTY AD CHRONOS included patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and an inadequate response to topical corticosteroids. These patients were treated with topical corticosteroids as well as dupilumab or placebo.6 LIBERTY AD CAFÉ included patients with a history of inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin, or for whom ciclosporin treatment was medically inadvisable.7 For these trials, the Dupixent Summary of Product Characteristics reports on mean EASI score reductions at week 16 of approximately 72%, 67%, 80% and 80%, respectively.13 Overall, we saw a 90% reduction in EASI score for the 29 patients with both a baseline and review score.

Other real-world evidence has looked at efficacy and safety at 52 weeks.14,15 These reports may have investigated different cohorts of patients and different efficacy measures, making direct comparisons difficult. Recognising that long-term ongoing treatment in patients with persistently controlled atopic dermatitis might lead to overtreatment and an increase in adverse events (e.g., injection site reactions, conjunctivitis), there is some limited research into how tapering of dupilumab dosing should be undertaken.16

As regards use of the EASI score: because this has moderate inter-observer reliability, it was suggested that the same investigator should perform the EASI in a patient at baseline and follow-up.17 This does not always occur in our centre; however, use of a tool such as EASI score.com18 (which has picture guidance) helps to reduce the subjectiveness of the scoring process.

We recognise the limitations of a single centre, very small-scale retrospective study that sampled approximately 34% of the patients recorded on Blueteq as having commenced dupilumab. We do not report prolonged follow up of patients in relation to any improvement in their atopic dermatitis other than what we observed documented in dermatology letters at commencement and review of treatment. These results therefore cannot be generalised to other hospitals.

Conclusion

In this very small study, 28 of 30 patients were compliant with NICE criteria for commencing dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. Two patients who did not achieve the required improvement at the 16-week review and had their treatment ceased.

Authors

Michael Wilcock BSc (Hons) MPhil

Leanne Roberson MAPharmT

Alison McInnes DIP(HE)Nursing/NIP

Pharmacy and Dermatology Departments, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Truro, UK

Declaration of interests: The authors have no interests to declare

Key points

References

First published on our sister publication Hospital Pharmacy Europe