This website is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Take a look at a selection of our recent media coverage:

14th June 2023

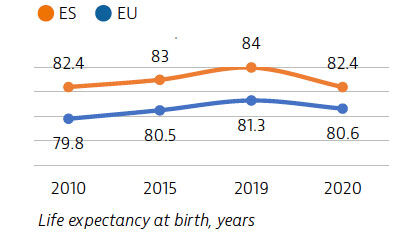

Life expectancy in Spain is among the highest in Europe, but it declined significantly in 2020 due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. On average, the Spanish population spends more time living in good health compared to other EU countries, but risk factors such as alcohol consumption have increased.

While the Spanish health system provides good access to high-quality care, the pandemic mobilised efforts on prevention and public health, temporarily increasing the health workforce and use of digital health. Universal health care and a strong primary care system have been key in the response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Life expectancy in Spain in 2020 was almost two years higher than the EU average, despite a fall of 1.6 years because of the high mortality registered during the Covid-19 pandemic. Before the pandemic, life expectancy had increased steadily in Spain by more than four years between 2000 and 2019, reaching 84 years in 2019. Historically, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and cancer have been leading causes of death.

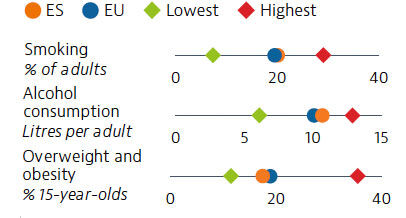

Risk factors for health are major drivers of mortality in Spain. While tobacco consumption has fallen over the past two decades, one in five adults still smoked daily in 2019. Alcohol consumption has increased and was slightly higher than the EU average in 2019. Some 18% of 15-year-olds were overweight or obese in 2018 – slightly below the average across EU countries.

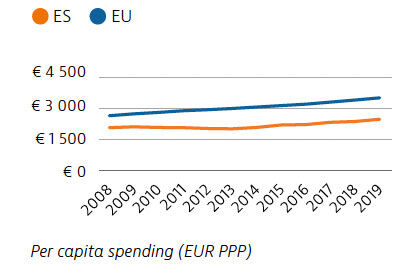

Spending on health per capita remains lower in Spain than the EU average. There is a growing gap between Spain and EU countries in total health spending, indicating slower growth over the past decade. Since 2014, per capita spending has been increasing, reaching €2,488 in 2019. Spain’s out-of-pocket payment levels are well above the EU average (at 21.8% compared to 15.4% of total health expenditure in 2019), and consist mainly of co-payments for medicines, medical devices outside hospitals and dental care.

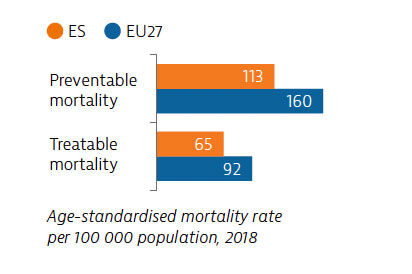

Mortality rates from preventable and treatable causes are lower in Spain than the EU average, boosted by effective public health and prevention policies before the Covid-19 pandemic. However, mortality rates from lung and colon cancer remain high.

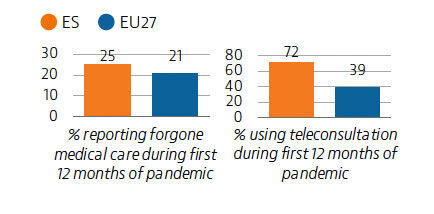

Access to health care is generally good in Spain. While unmet needs are very low for medical care, this is not the case for dental care. Access to health care services was disrupted during the first wave of the pandemic, but growing use of teleconsultations helped maintain access to care during the subsequent waves.

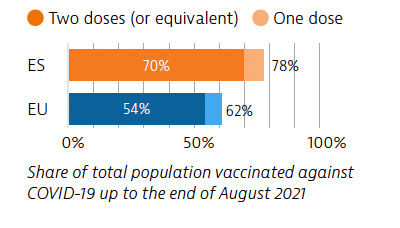

The Covid-19 pandemic had a severe impact on Spain and specific measures were taken to coordinate response efforts. Spain continuously updated its vaccination campaign and at the end of August 2021, its vaccination rate was significantly higher than the EU average.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Spain: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

13th June 2023

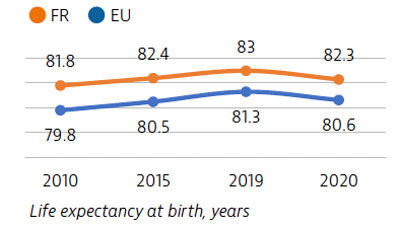

Life expectancy in France is among the highest in Europe, but it temporarily fell in 2020 because of deaths due to Covid-19. While the French health system provides good access to high-quality care, Covid-19 highlighted important structural weaknesses, including low investment in prevention, public health and health workforce.

The pandemic also stimulated many innovative practices that could be expanded to build a more resilient healthcare system.

Life expectancy in France in 2020 was almost two years higher than the EU average, but it fell by eight months because of deaths due to Covid-19. Even before the pandemic, gains in life expectancy had slowed considerably since 2010 compared with previous decades, partly due to increased mortality rates from influenza, pneumonia and other respiratory diseases among older people.

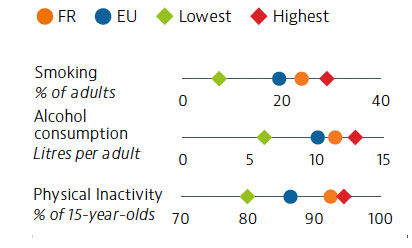

Behavioural risk factors for health are also major drivers of mortality in France. While tobacco consumption has fallen over the past two decades, almost one quarter of adults still smoked daily in 2019. Alcohol consumption has also decreased, but is still over 10% higher than the EU average. More than 90% of 15-year-olds reported not doing at least moderate physical activity each day in 2018 – the second highest share across the EU after Italy.

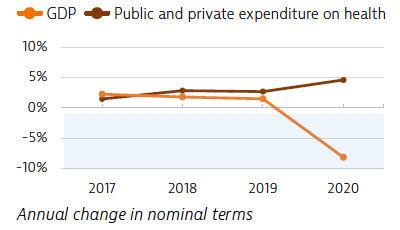

Spending on health per capita and as a share of GDP has been greater in France than the EU average for many years. Until 2020, spending on health was growing at around the same rate as the economy, but it increased more rapidly in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, while GDP fell by 8%.

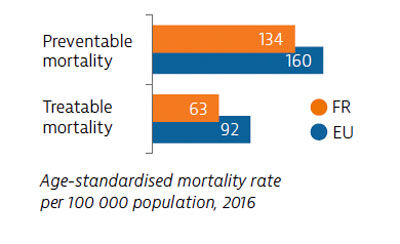

Mortality from preventable and treatable causes was lower in France than across the EU before the pandemic. However, France lagged behind some EU countries (Italy, Sweden, Spain) on preventable mortality, suggesting that more could be done to save lives by reducing risk factors for cancer and other leading causes of death.

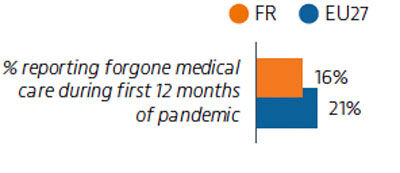

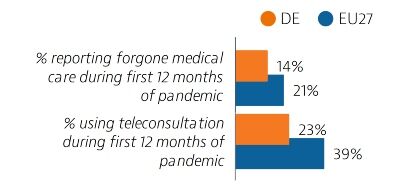

Access to healthcare is generally good in France, but it was hampered by Covid-19 in 2020. One in six people reported forgone care during the first 12 months of the pandemic; this is less than the EU average of 21% but higher than in Germany (14%). Growing use of teleconsultations helped maintain access to care during the various waves of the pandemic.

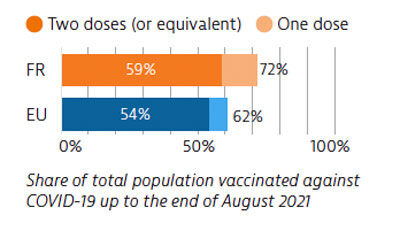

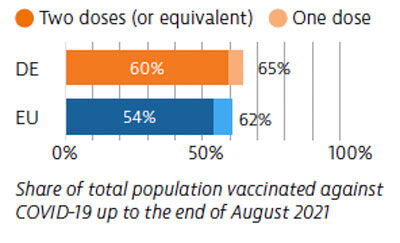

France was among the EU countries hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic in numbers of cases and deaths relative to its population size. The country accelerated its Covid-19 vaccination campaign in early 2021. As of end of August 2021, nearly 60% of the population was fully vaccinated (had received two doses or the equivalent).

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), France: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels

1st June 2023

The health status in Germany has improved over the last two decades, and life expectancy remains above the EU average despite the temporary reduction registered in 2020 that was caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Infection and death rates from Covid-19 in 2020 were lower in Germany than in most other EU countries. When measured as a share of GDP, health spending in Germany is the highest in Europe. The health system offers a generous benefits package, high levels of service provision and universal access to relatively high-quality and effective care. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed the challenges faced by federal systems in coordinating and managing such outbreaks.

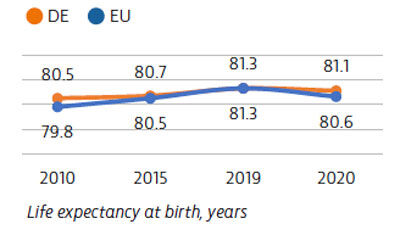

In 2020, Germany registered a life expectancy of 81.1 years – six months above the EU average but still somewhat lower than in EU countries with the highest levels. The Covid-19 pandemic had less of an impact on life expectancy in Germany than in the EU as a whole, having fallen by 2.5 months in 2020 compared to an average of just over eight months across the EU. The leading causes of death in Germany in 2019 were ischaemic heart disease, stroke and lung cancer.

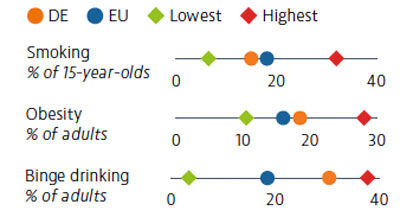

Around one in five adults smokes on a daily basis in Germany. While smoking rates have been declining, the growing popularity of e-cigarettes, particularly among young people, is a cause for concern. Adult and adolescent obesity rates are growing, and alcohol consumption among adults and 15-year-olds is considerably higher than the EU average.

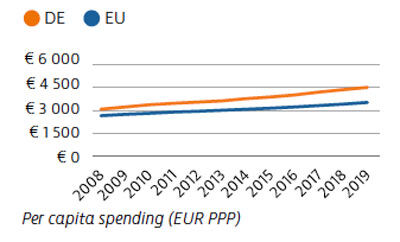

In 2019, Germany spent €4,505 per capita on health – the highest among EU countries, and 28% more than the average (€3,523). Germany also spends a greater proportion of its GDP on health (11.7%) than any other EU country. The majority of health spending comes from public sources; out-of-pocket payments amount to only 12.7%, which is well below most other EU countries.

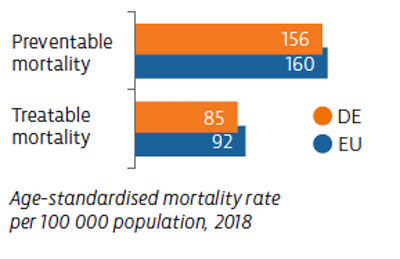

Mortality from preventable causes is lower in Germany than in the EU as a whole, reflecting the country’s effective public health and primary care system. Germany also has lower rates of death from treatable causes, owing to good access to effective treatments.

Access to care is generally good in Germany. Historically low rates for unmet needs rose during the Covid-19 pandemic when many non-urgent services were cancelled or postponed. One in seven people reported that they had to forgo needed care in 2020. However, the use of teleconsultations increased during the pandemic.

Despite well prepared health infrastructure and resources, Germany scaled up testing and laboratory capacities, intensive care unit beds and the health workforce. By the end of August 2021, around 60% of the population had received two Covid-19 vaccine doses.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Germany: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

18th May 2023

Organ shortage is a major survival issue worldwide and a disproportionate supply and demand was worsened by the pandemic, resulting in a significant decline in global transplant numbers. Here, Chloë Ballesté Delpierre, associate professor, University of Barcelona Medical School, details how countries need to learn from each other’s best practices and work towards a common goal to resolve this ongoing issue.

Organ transplantation is a life-saving procedure for many patients suffering from organ failure. However, the demand for organs far outweighs the supply, leaving many patients on waiting lists for years. The disparity between supply and demand was only worsened by the pandemic, the impact of which has resulted in a significant decline in global transplant numbers. In Europe, the scarcity of donor organs is a persistent issue that has yet to be fully resolved.

Organisations such as the World Health Organization, the European Union Commission and the Council of Europe have all made efforts to increase organ donation rates. However, despite several isolated actions, there has been very little improvement overall. Approximately 30,000 organs are transplanted in the EU annually, far below the estimated 150,000 patients on the waiting list.

While living donations can be a life-saving option for patients, they pose several ethical concerns. The pressure to donate from family and friends can be overwhelming, and the possibility of coercion or exploitation cannot be ignored. It is essential to ensure that donors are not put at risk while in pursuit of helping patients. Therefore, it is important to develop robust deceased donation programmes.

Most transplanted organs in the EU are from deceased organ donors, but these are still in short supply in many countries. Due to the lack of homogenised practices, organ donation rates vary from country to country. Each country also has its own legal and cultural framework, resulting in different consent systems, procurement procedures and allocation criteria.

Efficient donation programmes should be identified and promoted, with the nomination of a national competent authority and professionalisation within hospitals. Doctors from ICU, anaesthesia, emergency and any other departments caring for patients with severe neurological conditions should be duly trained and given the responsibility to lead the organ (and tissue) donation programme in their hospital. Focusing on the clinical activity and ensuring a regulatory framework would avoid fragmentation and unequal access to transplantation for patients.

To address these issues, the EU Commission launched an ‘Action Plan on Organ Donation and Transplantation’ to improve organ donation and transplantation in Europe. Between 2009 and 2015, the total number of transplants increased by 17% and the total number of deceased organ donors increased by 12%. But Covid-19 took a toll on the transplant community, and it is still trying to recover. There are new calls for an updated action plan considering the pandemic’s impact.

Despite the challenges, some countries have significantly increased their donation rates. Spain has one of the highest donation rates in the world, with 40.8 deceased donors per million population (pmp) in 2021 compared with the global average of 6.4 pmp. This is due to a combination of factors, including a well-structured donation system and a strong commitment from healthcare professionals.

To improve organ donation rates across Europe, countries need to learn from each other’s best practices and work towards a common goal, and the European Society of Organ Transplantation (ESOT) Congress helps make this possible. These meetings provide a unique opportunity for the transplant community to come together to share their knowledge and promote progress towards a better future for organ transplantation.

As an elected member of the ESOT Council and a member of the Scientific Programme Committee for the ESOT Congress 2023 in September, I am honoured to be involved in crafting a state-of-the-art programme, which will ultimately improve outcomes for patients with terminal organ disease and increase equitable access to organ transplantation.

28th April 2023

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the biggest challenges for hospitals and healthcare services to deliver safe and effective healthcare. A 2018 survey estimated that around 33,000 people die each year in the in the European Union and European Economic Area as a direct consequence of an infection due to bacteria resistant to antibiotics.

In 2020, the European Hospital and Healthcare Federation (HOPE) published a position paper on antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Here, the organisation’s chief executive Pascal Garel provides an update and offers his recommendations on prevention policies, fostering the One Health Approach and promoting the development of new antimicrobials.

The ‘One Health’ perspective of the European Commission’s Action Plan provides an opportunity for stakeholders representing different sectors and constituencies to provide expert inputs for improving the implementation of the Plan. This includes experts from the human health, animal health and food production, and environmental disciplines.

Hospital and healthcare providers are clearly important in this regard. Healthcare environments are places where antimicrobial-resistant bacteria emerge and spread, but also where actions can be particularly effective for preventing future outbreaks and ensuring prudent use of antimicrobials.

Other important voices involved in fighting antimicrobial resistance are: medical professionals, nurses, hospital and community pharmacists, students, infection prevention and control specialists and carers. In addition, it is relevant to include organisations with a broader remit, such as public health, health education and research-focused organisations, and those promoting solutions such as rapid diagnostics, vaccines and alternative medicines for veterinary uses.

It is not sufficient to rely exclusively on Member States’ own funding, given that there is a marked north-south and west-east gradient regarding consumption of antimicrobials and AMR prevalence. Moreover, the development and implementation of National Action Plans (NAPs) has been uneven. Over half of the Member States have no action plans, or have plans that are no longer valid or about to expire. A lack of access to funding – including the possibility to combine different funding programmes and projects to complement one another in the longer term – and of other resources, such as laboratory capacities, healthcare resources, infection prevention and control specialists, are often cited as main reasons.

Supplementing national budgets with a dedicated EU-AMR funding mechanism is necessary to close these gaps. Using the European Structural and Investment Funds and providing technical assistance through the European Structural Reform Support Programme is also needed.

The impact of Covid-19 on healthcare budgets and on the ability of hospitals and healthcare facilities to operate effectively should not be underestimated. Health worker shortages, supply issues related to PPE, and persistent budget cuts are stretching many health institutions to the limit. While it is clear that the size and immediacy of the AMR threat will necessitate the diversion of some national and institutional funds, this is not sufficient to solve the issue and could indeed exert a negative impact on other crucial areas, such as the ability to guarantee continuity of care during health security crises.

A key barrier is the need to develop, adopt and fund a long-term vision that exceeds the political mandates of most national governments and hence complicates endorsement and implementation of NAPs. Therefore, the role of the European Commission and of international groups – such as the WHO, G7 and G20 – is vital in avoiding AMR slipping off the political radar and any policies under development merely following a one-sided approach.

More tangible guidance on devising impactful antimicrobial resistance frameworks is required. This goes beyond listing actions to include dedicated funding pooled from different policy areas. Increased political instability and societal divisions – reared also by ‘fake news’ and conspiracy theories online – further complicate this task as decision-makers are primarily focused on short-term quick wins.

The pandemic crisis demonstrated that action can be taken quickly when needed: the problem being that the new EU health budget is the product of a reactive rather than proactive approach. However, the AMR threat is as serious as that of Covid-19, and concrete steps are required to move towards a European Health Union. These steps are driven by values of solidarity, with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control given an enhanced health security framework and extended powers for surveillance, preparedness and response planning.

There is growing awareness at national level that certain health-related problems – such as AMR – require enduring and targeted commitment as well as dedicated financial, human and technological resources. The EU One Health Network should be replicated at national level in recognition of the urgency.

We work in partnership with stakeholders representing the agricultural and veterinary areas as part of an AMR Stakeholder Network originally created under the European Health Policy Platform. The One Health perspective draws attention to the interlinkages between excessive uses of antibiotics in food production, animal husbandry and human health, among other things contributing to the rise of non-communicable chronic diseases and the growing threat of infectious diseases and pandemics, both, in turn, requiring functional antibiotic drugs to combat them.

Without being able to speak for the agricultural and veterinary sector, HOPE endorsed the AMR Stakeholder Network’s Roadmap. EU rules banning the routine use of antibiotics and restricting preventative uses to special circumstances are in place. However, the bigger change needed is moving away from highly intensive livestock farming systems involving both routine and excessive use of antibiotics. Available options include altering production systems by reducing stocking density, different breeds and so on; exploring alternatives to antibiotics; and antibiotic stewardship programmes.

Establishing an EU-wide antibiotic formulary is not feasible given the different healthcare needs, patient profiles and antimicrobial prescribing practices at national and regional levels. However, the existing EU Guidelines for the prudent use of antimicrobials in human health should be expanded. This could include more concrete information aimed at different professions. Some harmonised guidance for specific antimicrobials commonly used in all countries could contribute to better prescribing and handling in all Member States.

Member States developing stewardship programmes within the hospital sector, but also covering community and long-term care settings, with the help of EU funding ensures that healthcare professionals are well prepared to tackle multi-drug resistance. This would also facilitate cross-border cooperation and better ensure that AMR protocols are adhered to during serious health crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

A multidisciplinary approach to the implementation of stewardship programmes encourages mutual learning and transfer of expertise. This is more effective than offering lectures or encouraging self-study.

Antimicrobial stewardship should be part of educational curricula to inform students and trainees of antimicrobial resistance and encourage prudent use from the outset.

Dr Urmas Sule, HOPE president, details how Estonia has weathered the significant challenges of 2022 and his hopes and expectations for 2023.

In 2022, we moved from Covid-19 to an energy crisis and the uncertainty of war. Unfortunately, Covid is still very much present. Managing one crisis after another, and sometimes doing it simultaneously, proves a challenge for maintaining a reasonable balance of healthcare services for Covid and non-Covid patients. In my opinion, we have succeeded in guarding the patients’ interests and safety the best way.

During these difficult times, we saw how important it was to have smooth cooperation between hospitals and healthcare providers. An effective distribution of tasks and responsibilities was developed to protect patients’ interests in the best possible way.

We as hospital managers cooperate well with the Health Board, the Health Insurance Fund and the Government of Estonia. Continuous negotiations with the Government and the Health Insurance Fund about adequate financing of services and support for the health sector were necessary and proved very fruitful.

Our partnership with the Estonian Medical Association, the Medical Faculty of the University and the Health Care Colleges has been a big help in involving medical and nursing students.

Our main focus for 2022 was, and will always be, to protect our healthcare workers from burnout. This is not an easy task and needs good cooperation between all partners.

Similar to other European countries, Estonia also faces the problem of a shortage of healthcare workers. Healthcare specialists are working for multiple employers. This is good for knowledge exchange, but is difficult to organise in a pandemic situation. Shortages have been a problem in Estonia for a long time, not just during Covid. The pandemic intensified the problem. Ensuring a reasonable division of labour and responsibilities between hospitals and other healthcare institutions has been a challenge.

But there are also other barriers, too. Political priorities have shifted from solving the healthcare crisis to an energy crisis and the effects of war. The primary focus has been improving readiness for emergencies in all areas. Helping Ukrainian refugees, providing them with social security and healthcare services is one of the important and ongoing challenges.

The Estonian Government created a new crisis staff structure during Covid. This structure was adapted for the healthcare sector together with the Estonian Hospitals Association network. We have collaborated with the Estonian Health Insurance Fund to guarantee the best possible availability of healthcare services to all patients. This has been possible due to the prudent and flexible planning and financing of services.

To motivate employees, we have negotiated collective agreements in two-year increments. This has been a good opportunity to hear the needs and expectations of healthcare workers so we can do our best to try to meet those expectations and improve working conditions. Negotiations for the coming years are currently underway, and we will make all efforts to find a balanced agreement and retain the effective and trusting relationships among our social partners.

The Health Insurance Fund measures the need for health services to lessen the treatment deficit. In collaboration, we have negotiated and agreed on the measures to reduce treatment deficits for non-Covid patients. We planned and introduced new services to prepare for Ukrainian refugees entering the healthcare system. But the biggest challenge for hospitals is the rapid and continuous rising costs of energy and other services.

We have monitored hospitals’ workloads and cooperated to ensure best use of all resources – especially the healthcare workforce – to create a flexible system that is prepared for new challenges.

We have seen a rapid growth of the development and use of e-services and remote services and consultations in the healthcare sector in Estonia. There has been great development across many specialities – psychiatry, for example – during the pandemic. This has been possible due to the collaboration between hospitals, other healthcare providers and the Health Insurance Fund.

Because of the health crisis, we have increased infection control capacity and knowledge, not only in the healthcare sector, but also in society. A nationwide vaccination campaign has also alleviated the effects of Covid and the burden on the healthcare system.

We are negotiating the 2023/24 collective agreement with the Medical Association, Nurses Association and other trade unions. It is a challenge to achieve a balance between reasonable salaries and general pricing principles that include all input prices and guarantee adequate availability of patient services.

At the same time, our healthcare system has to achieve the best possible flexibility to be prepared for any possible crises. This seems like an endless and boundless task!

Artificial intelligence is a complex phenomenon. It will impact the way medical research is conducted, how biomedical data are used, and how healthcare professions and organisations are regulated.

In 2021, the European Hospital and Healthcare Federation (HOPE) published a position paper on artificial intelligence (AI). Here, the organisation’s chief executive Pascal Garel provides an update on this and outlines recommendations on how to ensure that the application of AI in healthcare benefits patients and consumers alike.

A Europe-wide operational definition cannot be implemented as what is perceived as ‘being for the common good’ in one sector might be ethically unacceptable in another. A rigid technical definition risks excluding less complex AI-based systems from the legal framework. An insufficiently clear definition could also inspire different legal interpretations at a national level, thereby defeating its purpose.

That is why HOPE is advocating a health sector-specific approach to AI. Personal health data are a particularly sensitive category. Leakage or misuse could lead to severe consequences and negative health outcomes. Members of vulnerable groups are especially powerless when it comes to refuting AI-enabled results or administrative decisions about entitlements. Safeguarding fundamental rights, data and privacy protection, and ensuring the safety and security of individuals contributing or using data, are essential.

While a risk-based approach as outlined in the European Commission’s AI Act has its merits, particularly in sectors where AI deployment is straightforward and the risks of abuse are minor, in a health context the nuances are stronger. Extra care is needed to prevent seemingly ‘low risk’ AI systems inadvertently harming individuals, by revealing their identities or drawing conclusions about them based on biased data. For example, fitness and wellness applications are commercial products and their standards and purposes differ from those of actual medical devices used in healthcare environments.

The uses outlined in the AI Act, as well as in the European Health Data Space (EHDS) are broad, to exploit the market potential of AI solutions as much as possible. Uses must be balanced with ethical and human rights considerations to build support for trustworthy AI.

Regarding the definition of AI in health, the health community should be provided with ample opportunities to co-shape AI policies. The debate is not only about technology, but also about the future of health systems and how healthcare is provided. This includes Member States’ ability to protect vulnerable populations from the ‘AI frenzy’ of Big Tech firms eager to reap profits from securing vast amounts of personal health data. It is about the impact of AI on everybody’s lives.

On the other hand, AI holds great potential to improve healthcare provision and health research. It could even ‘re-humanise’ healthcare if (co-)developed and deployed in an ethical, transparent, and inclusive way. It could, for example, take care of routine health administration and documentation tasks and provide crucial decision support in diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Many medical disciplines could gain from AI support and researchers could uncover links that were hitherto impossible to detect. Discussions should include patients, healthcare professionals, consumers, researchers, public health experts, and representatives of vulnerable groups and human rights groups.

Specifying the relevant healthcare settings that can benefit from AI would be beneficial to avoid any loopholes where the agreed rules do not apply. These might not need to be part of the definition of AI as such but could be outlined in a healthcare-specific protocol as part of the legislation.

It is difficult to capture the diversity of healthcare provision today as many Member States are experimenting with new models of care to lessen the pressure felt by the hospital sector. The AI legal framework should nonetheless reflect this multiplicity. This includes public, private and other categories of hospitals – whether focusing on providing general or specialised services – nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, outpatient facilities, ‘virtual wards’ and at-home care provision.

Artificial intelligence is used widely today, and new solutions come to market every week. A legal framework should be devised without delay. This framework needs to balance fostering AI innovation and international collaboration with being mindful of the consequences that could arise from the increased reliance on AI, including physical or mental harm and violation of fundamental rights. AI systems could potentially be adapted to uses other than their declared purposes. They could be deliberately or unknowingly misused and the results biased for various reasons.

Implementing AI on agreed socially and ethically acceptable uses would improve confidence. Instead, the proposed legal framework (AI Act coupled with the AI-relevant provisions in the European Health Data Space) is rather confusing and does not provide adequate information about what trustworthy AI in healthcare will look like in practice as the potential uses remain indistinct.

AI serves many different purposes in different fields. Dependence on it will only increase as Europe wishes to reap benefits from harvesting data across sectors. This is one of the biggest real barriers. Different sectors have their own AI needs and have developed their own terminologies, which complicates devising a common working definition. However, a broad and vague overall definition of AI – if supported by more precise sectoral delineations – is still better than a very narrow definition. The latter could lead to exclusion of certain categories of systems or else encourage developers to maintain that their systems do not classify as AI although they contain very similar features.

Creating a legislative framework is not only about terminology, but also about understanding the broader environment in which AI operates. Like any other technology, AI is dependent on infrastructure, the availability of quality data, and financial and human resources. In healthcare, developing – and properly communicating – a clear strategic vision for AI would alleviate common fears. And which would catapult it from ‘science fiction’ to a recognised tool for health systems to improve quality of care.

Another key barrier is that the European AI framework intersects and overlaps with many other existing or proposed EU laws or initiatives covering mandatory responsibilities for manufacturers and users of digital technologies and data. Proper implementation of GDPR must not be hampered by the development of an AI-specific legal architecture. This includes sectoral products (e.g., Machinery Directive, General Product Safety Directive) and legislation dealing with data liability and safety (e.g., Data Governance Act, Open Data Directive). Healthcare-relevant EU legislation must also be adapted.

Building a robust and future-oriented cybersecurity legal framework will be especially important for the development and protection of a rights-based, human-centric European approach to artificial intelligence.

The Spanish Ministry of Health (SMoH) coordinates collaboration between 18 health regions, scientific societies, patients and other stakeholders. Its overall objective is to improve patient safety in all clinical settings in the health service.

In this webinar, Dr Yolanda Agra Varela, General Director Public Health, SMoH, provides an overview of the Spanish Patient Safety Strategy. Initially implemented in 2006, stakeholders revised the strategy to cover 2015-2020. Here, Dr Agra Varela discusses the learnings from the strategy including the main barriers and facilitators identified.

Patient safety remains a health policy priority in France. The 12th Quality and Safety Network webinar, organised by HOPE and PAQS, describes how the third French national adverse events survey showed a statistically significant drop in preventable adverse events and of their severity between 2009 and 2019.

Learning objectives include:

Life expectancy in Austria is higher than the EU average, but fell sharply in 2020 due to Covid-19 deaths.

While the Austrian health system generally provides good access to high-quality care, the Covid-19 pandemic underscored some structural issues, including the need to pursue reforms to overcome fragmentation and strengthen primary care.

A strong digital infrastructure offers Austria the potential to build a more integrated and resilient health system.

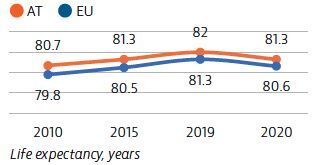

Although life expectancy in Austria in 2020 was more than half a year higher than the EU average, it fell by 0.7 year compared with 2019 because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Even before the pandemic, gains in life expectancy in Austria had slowed considerably between 2010 and 2019.

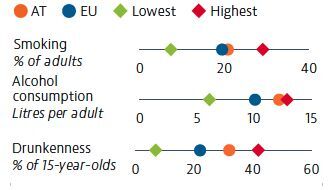

About 40% of all deaths in Austria in 2019 can be attributed to behavioural risk factors. Tobacco consumption among adults has fallen but remains slightly higher than the EU average. Alcohol consumption among adults in Austria is the second highest in the EU. Heavy alcohol consumption among adolescents is also higher than the EU average.

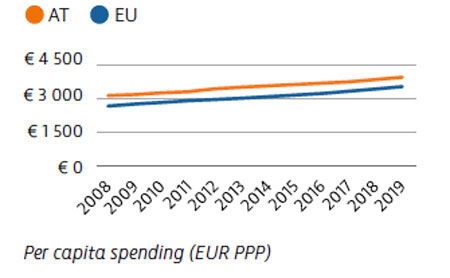

Spending on health per capita in Austria was the third highest in the EU in 2019. Austria spends substantially more than most countries on hospital inpatient care, while spending on prevention is lower than average. It also has relatively high numbers of physicians and hospital beds. While three quarters of all health expenditure is publicly funded, direct out-of-pocket spending by households is higher than the EU average.

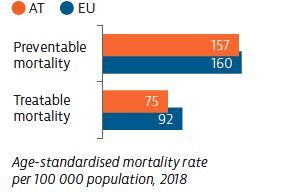

Mortality from preventable and treatable causes in 2018 was lower in Austria than the EU average. Nevertheless, Austria lagged behind many other EU countries on preventable mortality, suggesting that more could be done to scale up prevention and reduce risk factors for cancer and other leading causes of death.

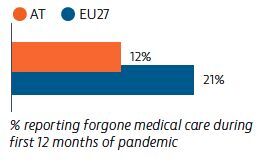

Access to healthcare is good in Austria, although Covid-19 created barriers to access. One in eight Austrians reported that they had forgone care during the first 12 months of the pandemic. Digital services helped to maintain access to care during the Covid-19 crisis: 35% of Austrians reported that they used teleconsultation services during the first year of the pandemic, which was slightly lower than the EU average.

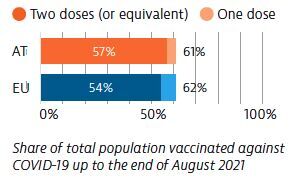

Between March 2020 and August 2021, confirmed Covid-19 case numbers in Austria were similar to the EU average, although the death rate was lower. By the end August 2021, more than 60% of the population had received at least one dose of a Covid-19 vaccine, and 57% had received two doses or the equivalent. These proportions were close to the EU average.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Austria: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.