This website is intended for healthcare professionals only.

Take a look at a selection of our recent media coverage:

4th July 2023

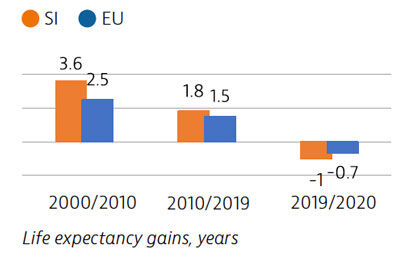

Life expectancy in Slovenia has increased markedly since 2000, but in 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily erased a year’s worth of gains. The Slovenian health system provides near universal coverage and a broad benefits package.

Voluntary health insurance plays a large role in covering co-payments levied on services; this also confers a considerable degree of financial protection from out-of-pocket payments.

The pandemic exacerbated or laid bare health system weaknesses, including workforce shortages, long waiting times, ageing hospital facilities and fragmented and underfunded long-term care.

Life expectancy in Slovenia had increased by over five years between 2000 and 2019. However, in 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic reversed this trend: life expectancy fell from 81.6 years in 2019 to 80.6 in 2020. Stroke, ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer are usually the main causes of mortality, but Covid-19 was responsible for the largest number of deaths in 2020.

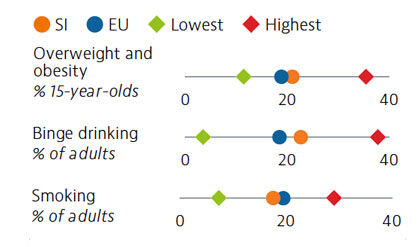

More than one fifth of Slovenian adolescents were overweight or obese in 2018. Alcohol intake among both adults and adolescents ranks above the average across EU countries, with binge drinking much more prevalent among male adults. Smoking prevalence has decreased for both adults and adolescents over the last decade, but over one in six adults are still daily smokers. The increasing popularity and use of e-cigarettes is also a concern.

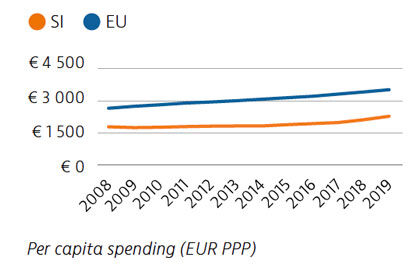

Health expenditure per capita has risen marginally over the last few years, but it remains well below the rate across the EU as a whole, as does spending as a share of GDP. Public financing of the health system accounted for 73% of health spending in 2019. Out-of-pocket spending is among the lowest in the EU, however, due mainly to extensive uptake of voluntary health insurance to cover co-payments.

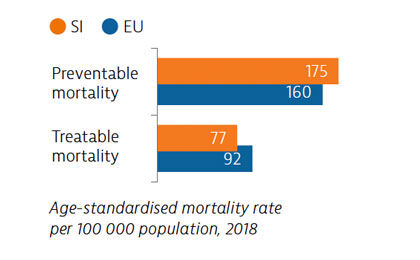

Mortality from preventable causes remains above the EU average. In contrast, mortality from treatable causes is lower than the EU average, indicating that the healthcare system is generally effective in providing care for people with potentially fatal conditions.

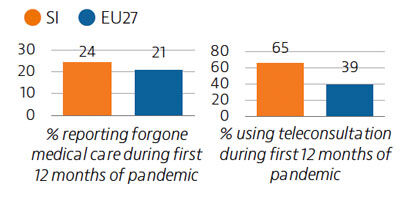

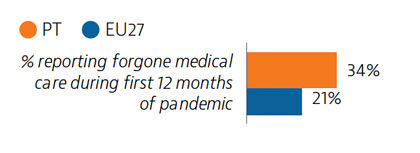

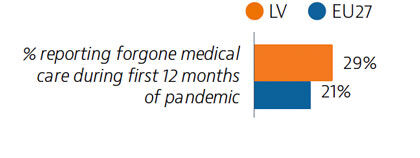

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, unmet needs for medical care were low, at 2.9% of the population, with waiting times the primary driver. In 2020, the demand for Covid-19-related care often led to delayed or forgone consultations and treatment for other health issues. Around 24% of the population reported forgone medical care during the first 12 months of the pandemic.

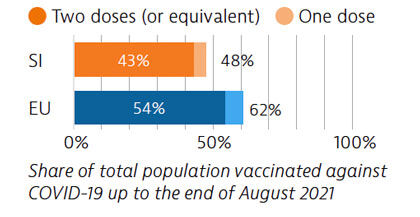

The Covid-19 pandemic revealed several resilience challenges, including workforce shortages and underdeveloped long-term care infrastructure prompting plans for more investment. Slovenia accelerated its vaccination campaign in spring 2021, and at the end of August 2021, 43% of the population had received two vaccine doses (or equivalent).

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Slovenia: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

3rd July 2023

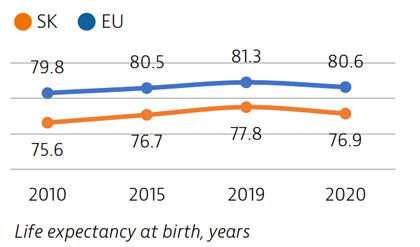

Life expectancy in Slovakia is among the lowest in Europe, and temporarily fell by almost one year in 2020 due to the impact of Covid-19. Behavioural and environmental risk factors contribute to nearly half of all deaths.

The Slovak population enjoys a broad benefits package, which includes recently introduced telemedicine. However, low levels of health spending and health workforce shortages remain persistent issues that were exacerbated by the pandemic.

Life expectancy in Slovakia increased by more than two years between 2010 and 2019, only to fall by almost one year in 2020 due to Covid-19 deaths. It remains nearly four years below the EU average. Disparities in life expectancy by socioeconomic status remain among the largest in the EU. Slovakia also has one of the highest cancer mortality rates in the EU.

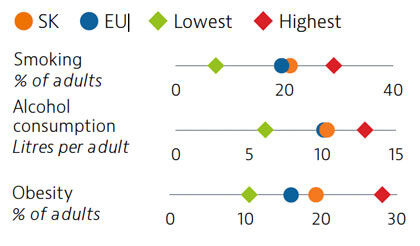

While adult tobacco consumption declined in most countries over the past decade, in Slovakia it remained stable and is currently above the EU average. Alcohol consumption is comparable to the EU average. Obesity rates among adults and adolescents are on the rise and higher than the EU average, due in part to poor nutritional habits and limited levels of physical activity.

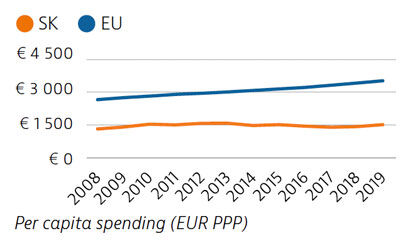

Slovakia spends less than half the EU average on health, at €1,513 compared to €3,521 per person in 2019, adjusted for differences in purchasing power. Around 80% of health spending is publicly financed, and out-of-pocket payments accounted for almost 20% of health expenditure in 2019 compared to 15.4% in the EU.

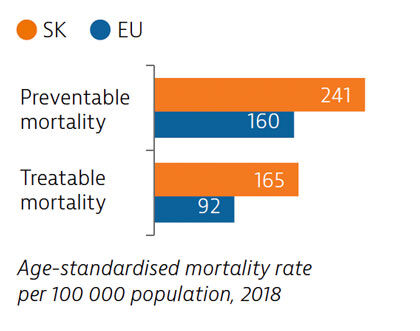

Slovakia has among the highest mortality rates from preventable and treatable causes in the EU. Despite improvements, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death. Substantial room for improvement remains for effective public health policies to reduce premature deaths.

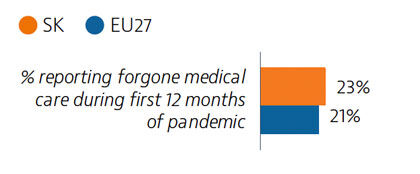

Access to healthcare is generally good in Slovakia, with only 2.7% of the population reporting unmet medical care needs before the pandemic. However, during the first 12 months of the pandemic, 23% of people reported forgone medical care. The introduction of telemedicine helped to maintain access to care during the second wave of the pandemic.

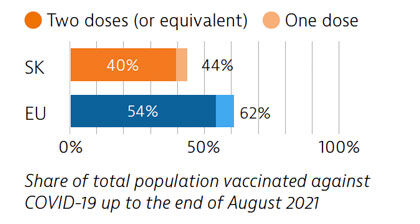

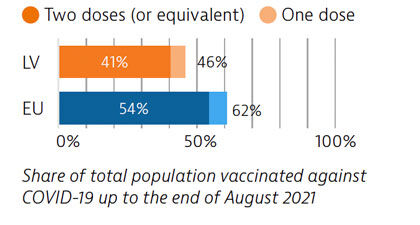

Slovakia had low Covid-19 case numbers during the first wave of the pandemic, due in part to quick implementation of containment measures. However, numbers rose significantly during the second wave; three quarters of all Covid-19 deaths occurred in the first half of 2021. As of August 2021, 40% of the population had received two vaccine doses (or equivalent) – a proportion lower than the EU average.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Slovakia: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Life expectancy in Romania is among the lowest in Europe, and the Covid-19 pandemic reversed some of the gains made since 2000. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of strengthening primary care, preventive services and public health, in a health system currently heavily reliant on inpatient care.

Health workforce shortages and high out-of-pocket spending are key barriers to access. The Covid-19 pandemic stimulated the creation of several electronic information systems to manage overstretched health resources better, and these may offer avenues to future health system strengthening.

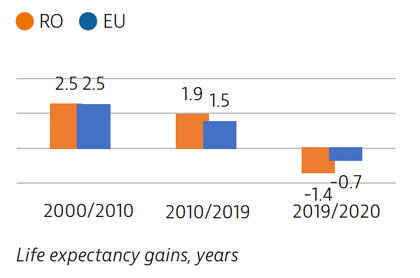

Life expectancy in Romania increased by more than four years between 2000 and 2019, but declined temporarily by 1.4 years in 2020 due to the impact of Covid-19. There is a marked gender gap, with women living almost eight years longer than men. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading causes of mortality while lung cancer is the most frequent cause of cancer death.

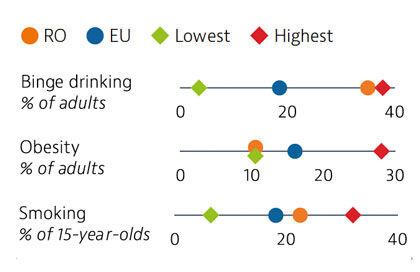

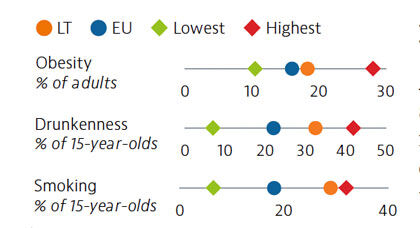

Risky health behaviours contribute to nearly half of all deaths. Romanians report higher alcohol consumption and unhealthier diets than the EU averages, but adult obesity is the lowest in the EU. Smoking in adults is now marginally lower than the EU average. These risk factors are more prevalent among men than women. Overweight, obesity and smoking rates among adolescents are high, and have been growing steadily over the past two decades.

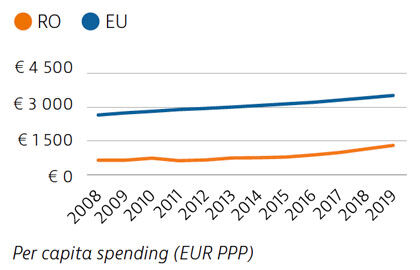

Health spending in Romania increased in the last decade but remains the second lowest in the EU as a whole – both as a share of GDP and per capita. About 44% of health spending was allocated to inpatient care in 2019, which is the highest proportion among EU countries. Although the public share of health spending is high and in line with the EU average, out-of-pocket payments are above the EU average and are dominated by outpatient pharmaceutical costs.

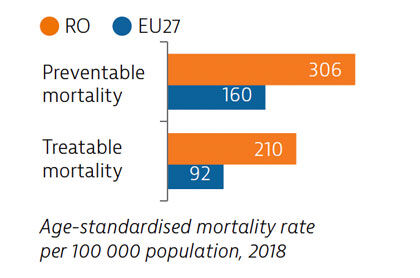

The preventable mortality rate is the third highest in the EU and can be attributed mainly to cardiovascular disease, lung cancer and alcohol-related deaths. Mortality from treatable causes is more than double the average for the EU and includes deaths from prostate and breast cancers that are amenable to treatment.

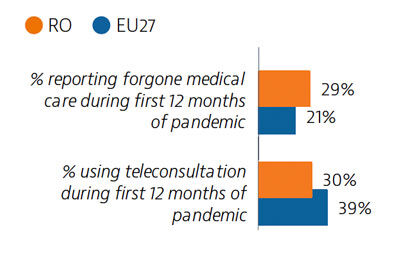

Although self-reported unmet needs for medical examinations had declined by more than half between 2011 and 2019, a high rate of forgone care was recorded in the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic. Teleconsultations were not used as widely as in other EU countries.

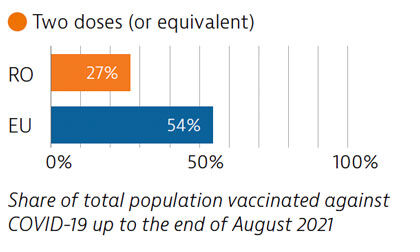

Before the pandemic, Romania invested significantly in the health sector, albeit from a low base, but Covid-19 put great pressure on the system. Planning and communication for the Covid-19 vaccination campaign began early, but the rollout was delayed due to supply shortfalls. Vaccination coverage is low, largely due to vaccine hesitancy.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Romania: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Life expectancy in Malta is the second highest among EU countries, but it declined in 2020 as a result of deaths during the Covid-19 pandemic. People spend more time living in good health compared to other EU countries, but rates of obesity are high and pose a major public health challenge.

Malta’s National Health Service provides good access to care, but the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted structural weaknesses in the health sector, including low hospital capacity, insufficient investment in prevention and gaps in the workforce.

Commitments to enhance the use of digital health, ongoing reforms to primary care and investment in physical infrastructure and the health workforce will help to build a more resilient healthcare system.

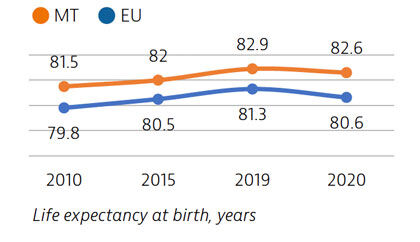

Life expectancy in Malta in 2020 was two years higher than the EU average. While it fell by 0.3 years due to the Covid-19 pandemic, this was below the average decline of 0.7 years seen across the EU. Deaths from cardiovascular disease and cancer have declined substantially in recent decades, but deaths from diabetes remain high. Self-reported good health among the population is high, but sizeable income-based inequalities in health status persist.

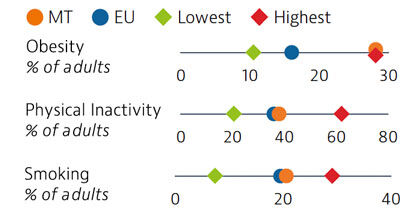

Rates of obesity in Malta are the highest in the EU, with more than a quarter of adults classified as obese. Poor diets and physical inactivity contribute to high levels of obesity in the country. Smoking rates among adults are similar to the EU average.

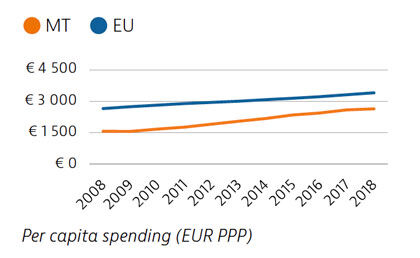

Malta has seen one of the largest increases in total health spending in the EU between 2008 and 2018, although expenditure per capita and as a share of GDP remained below the EU average in 2018. The share of funding from public sources also remained relatively low, and private out-of-pocket payments were among the highest in the EU. Public spending on health nevertheless increased substantially during the Covid-19 crisis.

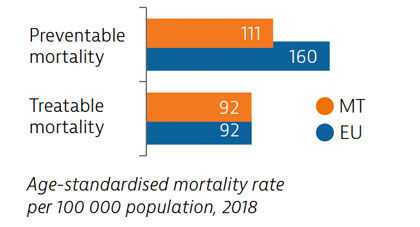

Mortality from preventable causes in Malta is among the lowest in the EU. Deaths from treatable causes have declined in recent years, and are now equal to the EU average. More deaths from cardiovascular diseases, cancers and diabetes could be avoided through more timely and effective diagnosis and treatment.

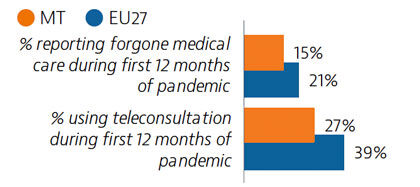

Malta’s health system provides good access to care, and levels of unmet needs for care were the lowest in the EU in 2019. One in six people reported having forgone care during the Covid-19 pandemic – a share lower than the EU average. Use of e-prescriptions, remote consultations and remote monitoring of Covid-19 patients helped maintain access to care during the pandemic.

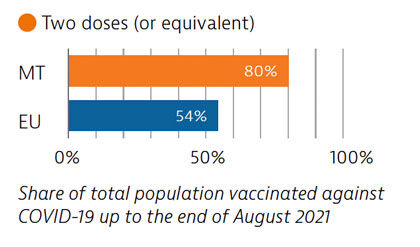

Widespread testing and comprehensive public health measures formed central components of Malta’s Covid-19 response. The country’s vaccination programme was also implemented rapidly, and by the end of August 2021, 80% of the population had received two doses (or equivalent) – the highest proportion in the EU at that time.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Malta: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Life expectancy in Portugal is slightly higher than the EU average, but it fell by nearly a year in 2020 because of deaths due to Covid-19.

While the Portuguese health system provides universal access to high-quality care, the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted some structural weaknesses, including low investment in the health workforce and equipment. However, the pandemic also stimulated several innovative practices that could be expanded to build a more resilient health system in the future.

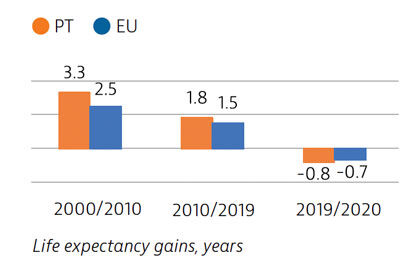

Life expectancy in Portugal in 2020 was half a year higher than the EU average, although it fell temporarily by 0.8 years between 2019 and 2020 because of deaths due to Covid-19 – a reduction close to the EU average. Before the pandemic, life expectancy in Portugal had increased by more than five years between 2000 and 2019. The burden of non-communicable diseases is high, and cardiovascular diseases and cancer are the leading causes of death.

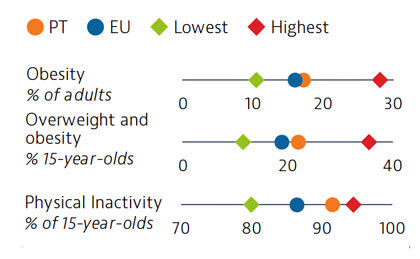

Approximately one third of all deaths in Portugal in 2019 can be attributed to behavioural risk factors. Overweight and obesity are growing public health issues among adults and young people. In 2018, 22% of 15-year-olds were overweight or obese, which is higher than the EU average. Low physical activity is one factor contributing to increasing rates of overweight and obesity

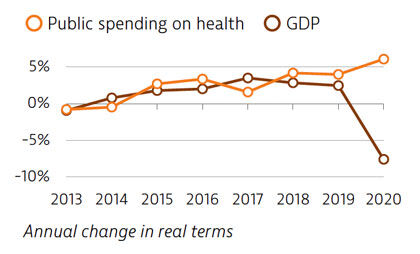

Spending on health per capita and as a share of GDP has been lower in Portugal than the EU average for many years. In 2019, Portugal spent €2,314 per capita on health, which is one third less than the EU average of €3,521, and health spending accounted for 9.5% of GDP (lower than the 9.9% EU average). The Covid-19 pandemic led to increased public spending on health in 2020, while the GDP fell sharply.

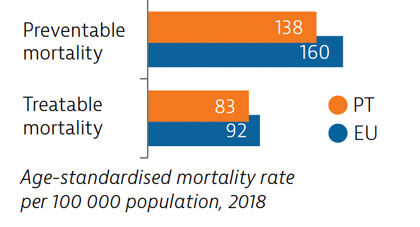

Mortality from preventable and treatable causes was lower in Portugal than the EU average in 2018. However, Portugal lagged behind some EU countries (such as Italy, Spain and France) on preventable mortality, suggesting that more could be done to save lives by reducing risk factors for leading causes of death such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

In 2019, a very small proportion of people reported some unmet medical needs due to cost, distance or waiting time, although this proportion was higher among those in the lowest quintile. Unmet medical care needs were much higher for all population groups during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, rapid expansion of teleconsultations helped maintain access to care during the pandemic.

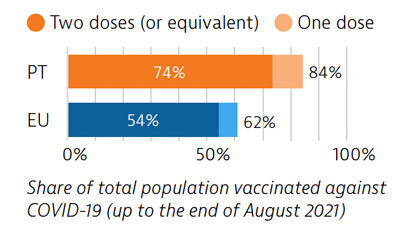

Portugal was among the EU countries hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. A broad testing strategy was supported by sufficient laboratory capacity, but containment of community transmission proved challenging. As of the end of August 2021, 74% of the Portuguese population had received two doses (or equivalent) of a Covid-19 vaccine.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Portugal: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Three coverage schemes provide broad health coverage to nearly all of the population of the Netherlands. These include a competitive social health insurance system for curative care, a single-payer system for long-term care and municipal systems for social care.

Like the rest of Europe, the Netherlands faced high pressures from the Covid-19 pandemic, and experienced a temporary drop in life expectancy in 2020. The unprecedented strain caused by Covid-19 posed a clear challenge at all levels of the Dutch health system.

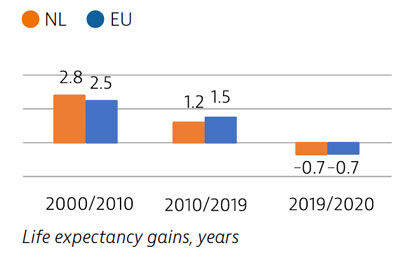

Life expectancy in the Netherlands is higher than the EU average by about one year, but gains have slowed over the past decade. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, life expectancy fell by 0.7 years between 2019 and 2020 – the same as the EU average. Lung cancer, stroke and ischaemic heart disease made up the highest share of mortality in 2019. In 2020, one in 15 deaths were attributed to Covid-19.

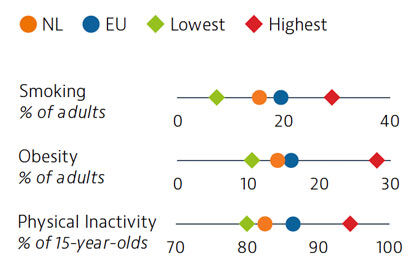

Behavioural risk factors in the Netherlands account for a lower share of deaths than the EU average. Smoking and obesity rates are both below the EU averages. However, one in five deaths in 2019 resulted from tobacco consumption – a higher share than in the EU – and obesity levels among adults have increased over the last two decades. Dutch adults and adolescents are more physically active than those in most other EU countries.

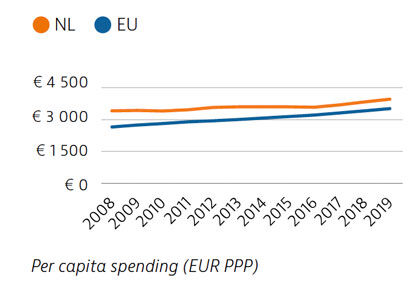

The Netherlands spends more per capita (€3,967) on health than the EU average (€3,523), with a considerable share dedicated to long-term care. Expenditure on outpatient pharmaceuticals and medical devices is kept low, aided by volume and price control policies and well-established health technology assessment processes. Public sources cover a high percentage of health expenditure, resulting in a lower share of out-of-pocket spending for healthcare than the EU average.

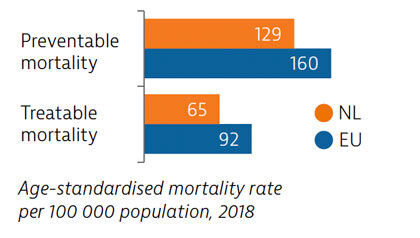

The Netherlands has among the lowest mortality rates from preventable and treatable causes in the EU. Most preventable deaths are from lung cancer, while colorectal cancer and breast cancer account for 40% of deaths from treatable causes. Mortality rates from ischaemic heart disease, stroke and pneumonia are among the lowest in the EU.

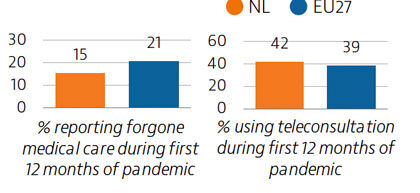

The Dutch population has historically reported low unmet needs for medical treatment, but this changed during the Covid-19 pandemic when many non-urgent services were cancelled or postponed. Evidence suggests that 15% of people had to forgo care during the first 12 months of the pandemic. Teleconsultations were used to help maintain access to services.

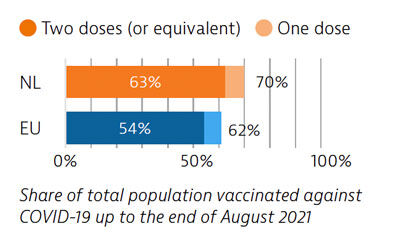

The health system response to Covid-19 encountered obstacles, including fragmentation in testing, contact tracing and vaccination efforts. After a slow start, the vaccination campaign accelerated, and 63% of the population had received two doses (or equivalent) by the end of August 2021.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), The Netherlands: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Luxembourg has seen a continuous increase in life expectancy up to 2019, but there was a significant fall in 2020 because of deaths due to Covid-19. Behavioural risk factors contribute to more than one third of all deaths, with high alcohol consumption and growing obesity rates of particular concern.

Luxembourg’s population enjoys good access to health care, with a broad benefits package and low out-of-pocket payments.

Luxembourg reacted rapidly to the Covid-19 pandemic with implementation of a large-scale testing strategy, teleconsultations, a national reserve of health professionals and a reorganisation of primary care.

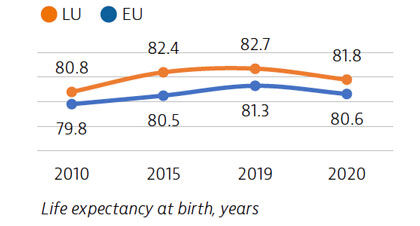

Life expectancy at birth in Luxembourg increased by nearly two years between 2010 and 2019. Although it then fell by nearly one year in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, it is still above the EU-wide average. Despite reductions in ischaemic health disease and stroke rates, they remain the leading causes of death, along with lung cancer.

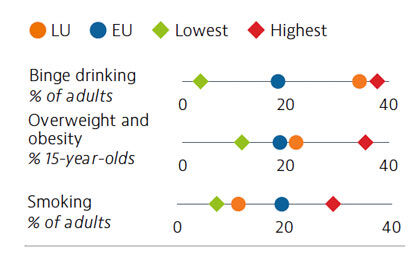

Behavioural risk factors – especially poor nutrition, smoking, physical inactivity and alcohol consumption – are major drivers of morbidity and mortality in Luxembourg. One in three adults report binge drinking behaviour, which is the third highest rate in the EU. Overweight and obesity levels and physical inactivity among 15-year-olds are above the EU average. On a more positive note, smoking levels have declined since 2001 for both adults and adolescents.

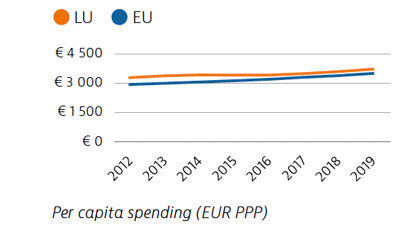

In 2019, Luxembourg spent €3,742 per capita on health (adjusted for purchasing power parity), which is relatively high compared to the EU average of €3,523. The public share of total health spending (85%) was also above the EU average. In 2020, public spending on health increased sharply in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

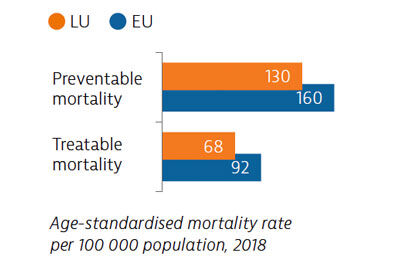

Preventable mortality is lower than the EU average, reflecting the effectiveness of prevention policies. Treatable causes of mortality are also low, indicating that the health system provides effective primary and acute care for potentially fatal conditions.

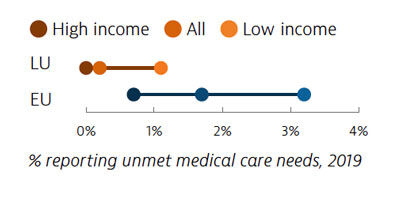

Coverage of health services in Luxembourg is generally good, and unmet needs for care are among the lowest in the EU. However, during the first 12 months of the Covid-19 pandemic, one in five people reported forgoing medical care – slightly lower than the EU average. Growing use of teleconsultations helped to maintain access to care during the various waves of the pandemic.

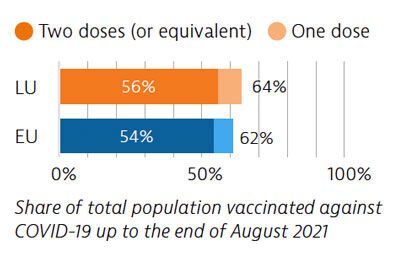

Luxembourg responded rapidly to the pandemic, and set up various measures such as largescale testing and effective contact tracing. The vaccination campaign was rolled out in six phases. As of the end of August 2021, 56% of the population had received two doses of Covid-19 vaccine (or equivalent).

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Luxembourg: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

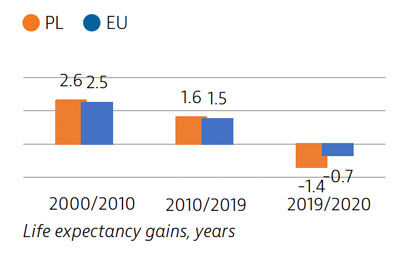

In 2020, Poland temporarily lost 1.4 years of life expectancy compared to 2019 because of deaths due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The Polish health system has been suffering from low levels of public financing for many years; this is reflected in workforce shortages and access problems such as long waiting times and high out-of-pocket payments.

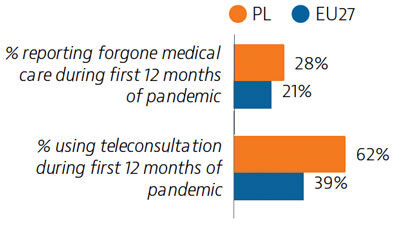

While the Covid-19 pandemic stimulated unprecedented use of teleconsultations in primary care, non-Covid-19 patients faced barriers to accessing specialist care. Workforce shortages were brought into focus as the key bottleneck in surging care capacity during the pandemic.

Life expectancy in Poland in 2020 was 76.6 years – four years lower than the EU average. High excess mortality due to the Covid-19 pandemic caused life expectancy to fall by 1.4 years between 2019 and 2020, which was among the largest reductions observed in the EU. Ischaemic heart disease, stroke and lung cancer were the main causes of death before the pandemic, but Covid-19 accounted for a substantial share of deaths in 2020.

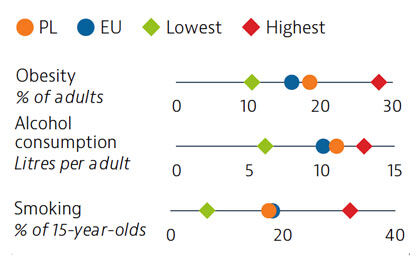

Almost half of all deaths in Poland are driven by behavioural factors, such as smoking, binge drinking and physical inactivity. Obesity has been growing and almost a fifth of adults are now obese – a higher share than in the EU. While alcohol consumption among adults has been rising, smoking rates among both adults and adolescents have been decreasing. Nevertheless, the growing popularity of e-cigarettes among young people is a concern.

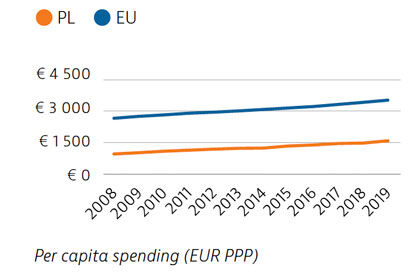

Over the past decade, spending on health in Poland has remained consistently below the EU average, both in per capita terms and as a share of GDP. The Covid-19 pandemic prompted additional funding injections in 2020 to support the health sector response. Around 72% of Poland’s health spending comes from public sources, but out-of-pocket spending is high, accounting for just over 20% of current health expenditure – mostly for outpatient medicines.

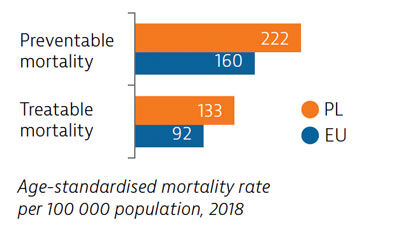

Mortality from both preventable and treatable causes in Poland is above the EU average. Efforts are being made to tackle obesity and there is also scope to strengthen tobacco and alcohol policies to improve population health. Cancer survival rates have improved but remain comparatively low.

The level of unmet needs before 2020 was relatively high in Poland and this continued during the Covid-19 pandemic. The growing use of teleconsultations helped maintain access to primary care during the pandemic, but access to specialist care was severely restricted for non-Covid-19 patients.

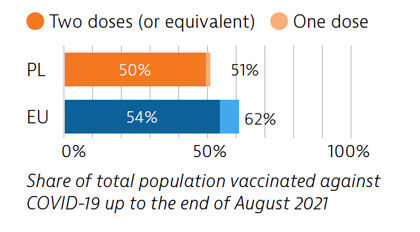

Primary care progressively became the first line of Covid-19 response, but limited testing and contact tracing capacity have persisted. By the end of August 2021, half the population had received two doses (or equivalent) of a Covid-19 vaccine, but vaccine hesitancy is slowing the rollout of the vaccination programme.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Poland: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

Despite progress before the Covid-19 pandemic, life expectancy in Latvia remains low compared to other EU countries due to the relatively high prevalence of behavioural risk factors, as well as low public spending on health and care accessibility issues.

While Latvia was largely spared from the first wave of Covid-19, towards the end of 2020 the infection rate spiked, bringing to light issues around equipment and staff shortages. To support the healthcare system during the pandemic, the government made available additional funding for equipment, staff bonuses and structural improvements.

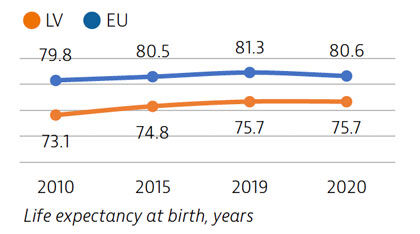

Despite significant gains over the past two decades, the life expectancy of the Latvian population remains among the lowest in the EU. Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted the steady growth trend in 2020. The gender gap in life expectancy is more than nine years – the second highest in the EU – and the life expectancy of Latvians varies considerably by educational level.

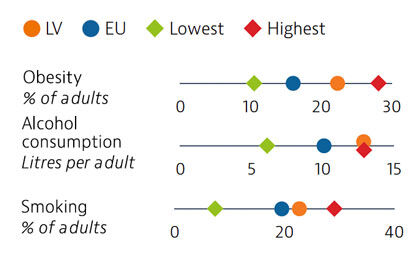

Latvia faces a considerable health burden from behavioural risk factors: the country has the highest level of alcohol consumption in the EU, and one in four men binge drink monthly. The proportions of obese adults and adults who smoke daily are well above the EU average. The Ministry of Health has developed a number of plans and policies to reduce these risk factors over the coming years.

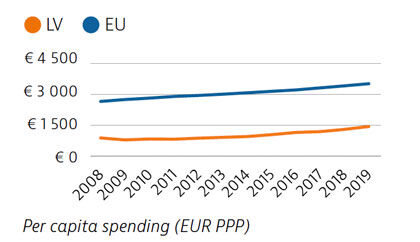

Latvia has a national health system with strong government stewardship, but which remains severely underfunded. Even though health expenditure per capita has increased by 75% since 2010, the level remains the fourth lowest in the EU. Only 61% of health expenditure is publicly funded, and the share of out-of-pocket spending is the second highest in the EU.

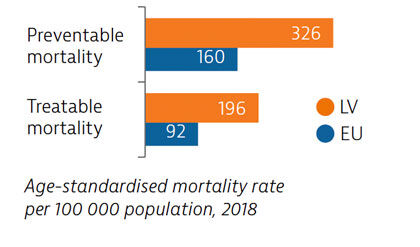

Latvia’s mortality rates from both preventable and treatable causes are the second highest in the EU. Cancer screening rates are low, despite efforts to increase uptake; this is reflected in high mortality rates for screening-amenable cancers. The Ministry of Health has a clear strategic focus on prevention and health promotion, but resources are limited.

Unmet needs in Latvia were among the highest in the EU, both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. This is driven by high out-of-pocket expenditure and a benefits package that is comparatively narrow and limited by a quota system. As a result, 15% of households experienced catastrophic spending on health. The uneven geographical distribution of health professionals creates further barriers to access.

While the impact of the first wave of Covid-19 in Latvia was moderate, by the end of 2020, the infection rate and mortality rate increased greatly, and equipment, personnel and bed shortages occurred. The government provided funding support to the healthcare system during the pandemic. By the end of August 2021, 46% of the population received two doses or equivalent, which was below the EU average.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Latvia: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.

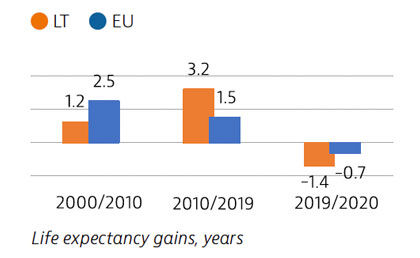

After years of steady gains in population health, the high mortality registered during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 in Lithuania temporarily caused a large drop in life expectancy of 1.4 years compared to 2019. The pandemic is also likely to undermine progress in disease prevention by disrupting priority programmes for the early detection of chronic conditions and cancers.

Longstanding challenges remain, such as low uptake of health promotion measures, uneven distribution of human resources, weak primary care and varying quality in specialist care.

Covid-19 gave a major impetus to the rapid further development of e-health, by transforming digital services, data collection and reporting.

Life expectancy in Lithuania in 2020 was the third lowest in the EU and 5.5 years below the EU average. Although the increase in life expectancy between 2010 and 2019 in Lithuania was the fastest in the EU, the impact of Covid-19 was a major setback, with 17% more deaths registered in 2020 than 2019. Fewer than half the population, and only one quarter of low-income households, reported being in good health – the lowest shares in the EU.

Adolescents in Lithuania are more affected by risk factors such as smoking and excessive drinking than the average in the EU. Alcohol consumption remains a major public health issue, even though consumption levels fell by one quarter between 2012 and 2019 due to stricter alcohol control measures targeting younger people.

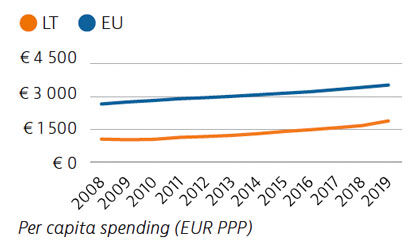

Health expenditure in Lithuania in 2019 is comparatively low, at just under €1,900, but it has grown slightly faster than the EU average. The share of out-of-pocket spending in total is double the EU average, at 32% in 2019. In 2020, a large share of the health insurance fund reserve was used to cope with the impact of Covid-19 on the health system.

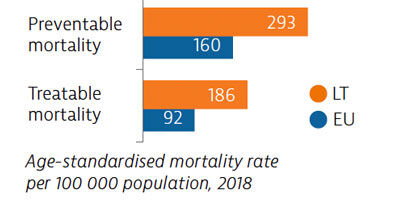

Treatable mortality in Lithuania was double the EU average in 2018, as effectiveness of primary and hospital care lags behind many EU countries. The Covid-19 pandemic caused major disruption for disease prevention programmes tackling cardiovascular diseases and treatable cancers, as well as for planned specialist care, but mental healthcare provision was enhanced.

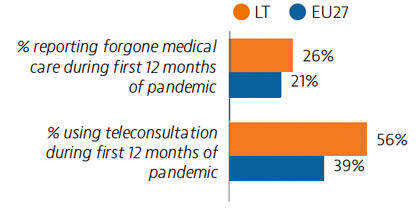

Despite comparatively low unmet needs before 2020, 26% of Lithuanians reported forgoing medical care during the pandemic, although many used teleconsultations for the first time. Out-of-pocket payments and the limited availability of healthcare workers outside the major cities also contributes to inequitable access.

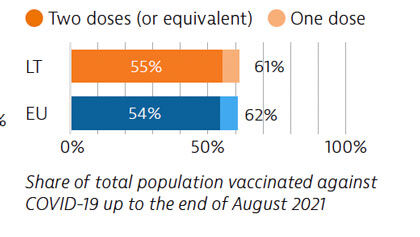

The ability to use beds flexibly and redeploy healthcare workers helped Lithuania to cope with surges in demand during the pandemic, albeit by severely limiting non-Covid-19 service provision. Vaccination rollout has been on par with the EU average, with 61% of the population receiving at least one dose and 55% receiving at least two doses or equivalent by the end of August 2021.

OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Lithuania: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels.