The figures presented provide the most up-to-date comparative picture of the situation of healthcare and hospitals, compared with that at the beginning of the 2000s

For a number of years, hospitals have been required to act more efficiently and to increase productivity. Increased performance is indeed evident. Yet, healthcare systems are facing conflicting trends: short and long-term impacts of financial and economic restrictions; increasing demands of an ever-expanding and ageing population, which leads to more chronic patients; increasing request and availability of technological innovations; new roles, new skills and new responsibilities for the health workforce.

To adapt to this situation, the role of hospitals is further evolving. Most health systems have already moved from a traditional hospital-centric and doctor-centric pattern of care to integrated models in which hospitals work closely with primary care, community care and home-care.

The figures given here provide the most up to date comparative picture of the situation of healthcare and hospitals, compared with the situation at the beginning of the 2000s. They aim to increase awareness on what has changed in hospital capacity and, more generally, in secondary care provision within European Union member states, generating questions, stimulating debate, and, in this way, fostering information exchange and knowledge sharing.

The sources of data and figures are the Health For All Database (WHO/Europe, European HFA-DB, February 20181) of the World Health Organisation and OECD Health Statistics (OECD.Stat, November 2017). All European Union member states belonging to OECD are considered, plus Switzerland and Serbia (as HOPE has members in both countries), when data are available. In the text, these are reported as EU. Whenever considered appropriate and/or possible two groups have been differentiated and compared: EU 15, for the countries that joined the EU before 2004 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom); and EU 13, for the countries that joined the EU after 2004 (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia). When averages on EU 28, EU 15 and EU 13 are reported, these generally refer to year 2014 and have been extracted by the Health For All Database. The considered trends normally refer to the years 2000–2015. When data on 2015 are not available, or they have not been gathered for a sufficient number of countries, the closest year is considered. Some figures are disputed for not being precise enough but at least they give a good indication of the diversity.

Financial resources for healthcare

From 2000 to 2016, the total current health expenditure expressed in purchasing power parity (PPP$) per capita increased on average by 120% in the EU. Inpatient care, out-of-pocket payments and pharmaceutical expenditures, in particular, showed growing trends in the considered years.

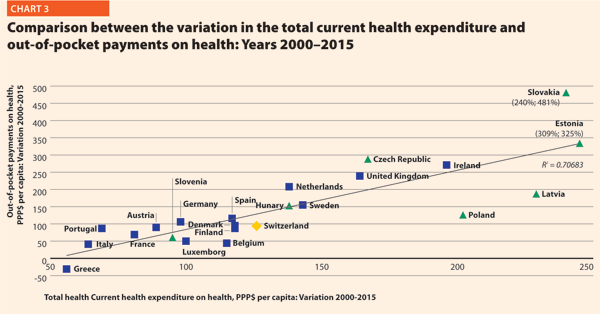

In EU 15, the amount of total current health expenditure per capita in 2016 was encompassed between 2223 PPP$ in Greece and 7463 PPP$ in Luxembourg while in EU 13, this range varied from 1466 PPP$ in Latvia to 2835 PPP$ in Slovenia. In Switzerland, this indicator reached 7919 PPP$. Compared with 2000, the total health expenditure per capita in 2016 varied positively in all the countries taken into consideration in this analysis. Major increases have been registered in Ireland (+210%), Poland (+219%), Latvia (+236%), Slovakia (+257%) and Estonia (+309%).

Public current health expenditure includes all schemes aimed at ensuring access to basic health care for the whole society, a large part of it, or at least some vulnerable groups. Included are: government schemes, social health insurance, compulsory private insurance and compulsory medical savings account. Private current health expenditure includes voluntary health care payment schemes and household out-of-pocket payments. The first component includes, in turn, all domestic pre-paid health care financing schemes under which the access to health services is at the discretion of private actors. The second component corresponds to direct payments for health care goods and services from the household primary income or savings: the payment is made by the user at the time of the purchase of goods or use of service.2

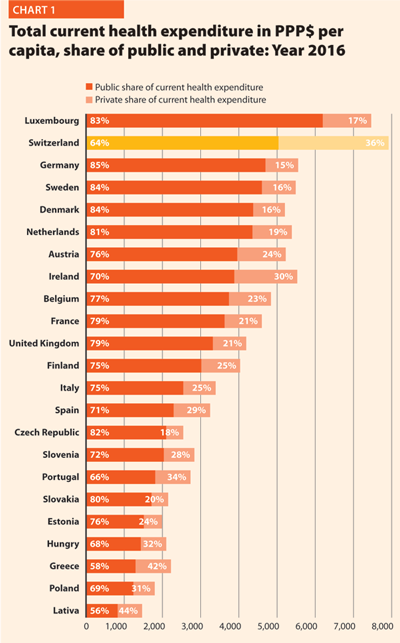

In 2016, the percentage of public sector health expenditure to the total current health expenditure was higher than 70% in most countries, except for Latvia (56%), Greece (58%), Portugal (66%), Hungary (68%) and Poland (69%) and outside the EU, in Switzerland (64%) (Chart 1).

Between 2000 and 2016, the public health expenditure in PPP$ per capita more than doubled in all the EU countries except in Greece (+49%), Portugal (+63%), Italy (+71%), France (+84%)and Austria (+84%). However, from 2008 to 2016, the variation was less significant than from 2000 to 2008.

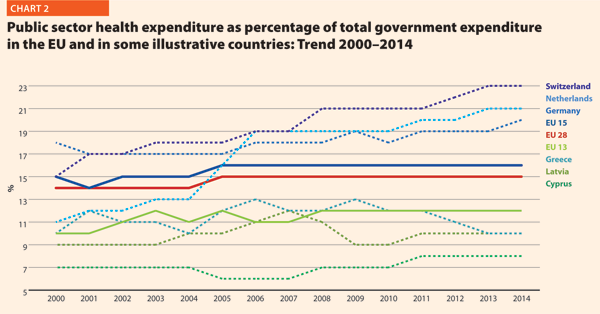

Chart 2 shows the last 14-year trend concerning the share of government expenditure in health. It presents the aggregated data concerning the EU, EU 15 and EU 13, and the figures of the three countries having the highest and the lowest values in the year 2014, Switzerland included.

In 2014, the percentages of government expenditure devoted to health differed by 4 percentage points (p.p.) between EU 15 (16.2%) and EU 13 (11.9%); Switzerland shows 22.7%, higher but also growing faster than the EU member states.

The trends illustrated in Chart 2 are generally positive between 2000 and 2006 with an average increase of percentage of government outlays devoted to health by 0.2 p.p. per year. Yet, from 2006 onwards, this way of development slackened off in many countries. The reasons can be the beginning of economic difficulties or in the shift of interest and priorities to other sectors.

Out-of-pocket payments show the direct burden of medical costs that households bear at the time of service use. Out-of-pocket payments play an important role in every health care system. In lower-income countries, out-of-pocket expenditure is often the main form of health care financing.3

In 2015, the private contribution to healthcare spending was around 20.0 % in the EU. It was higher than 25% in Portugal (27.7%), Switzerland (28.8%), Hungary (29.0%), Greece (35.5%) and Latvia (41.6%); it was lower than 10% only in France (6.8%).

Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of out-of-pocket payments to total health expenditure steadily declined. In EU 15, reductions were registered in Finland (-3.3 p.p.), Luxembourg (-3.6 p.p.), Italy (-3.6 p.p.) and Belgium (-8.7 p.p.) while increases were observed in Portugal (+2.7 p.p.), Netherlands (+2.8 p.p.), Ireland (+3.0 p.p.) and the United Kingdom (+3.3 p.p.). In EU 13, according to available data, the abovementioned percentage increased in Hungary (+1.7 p.p.), Estonia (+2.4 p.p.), Czech Republic (+4.6 p.p.) and Slovakia (+7.6 p.p.) and decreased in Slovenia (-2.6 p.p.), Latvia (-6.0 p.p.) and Poland (-7.9 p.p.). The total out-of-pocket payments in PPP$ per capita continued to increase, because the total health expenditure did.

Chart 3 illustrates the trend 2000–2015 of both the total current health expenditure per capita and the private households’ out-of-pocket payments on health. These values present a correlation (R² = 0.7068) showing that there is dependence between the two indicators. The chart highlights the fast growth of both expenses in the countries located in the upper part of the graph. In the ones in the lowest-left part of the graph, the out-of-pocket payments grew more slowly compared with the total current health expenditure.

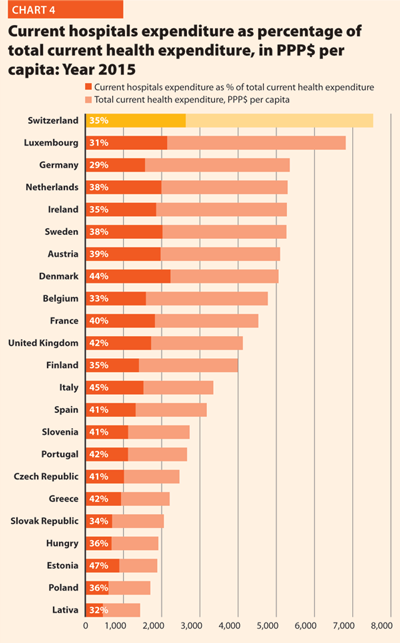

More than a third of current health expenditure (excluding investments and capital outlays) finances hospital care. The funds allocated to providers of long-term care, ancillary services, ambulatory care, preventive care, as well as to retailers and other providers of medical goods, are excluded from this computation.

In 2015, current hospital expenditure represented approximately 38.2% of total current health expenditure, ranging from 29.2% and 31.5% in Germany and Luxembourg, respectively, to 45.4% and 47.2% in Italy and Estonia (Chart 4). In all countries, even if a part of the total health expenditure is always funded by private insurances and out-of-pocket payments, almost the entire amount of inpatient health expenditure is publicly financed. The total expenditure on inpatient care (PPP$ per capita) in the EU follows, on average, a growing positive trend. The exception is Greece, where available data show that this indicator varies negatively (-23.0%).

Pharmaceutical expenditure includes the consumption of prescribed medicines, over-the-counter and other medical non-durable goods. One of the indicators taken into consideration for 2015 was expenditure on pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durable goods, as percentage of current health expenditure. The countries that registered the lowest rates of this indicator are Denmark (6.8%), the Netherlands (7.9%), Luxembourg (8.6%) and Sweden (9.9%) while the highest one were Poland (21.0%), Greece (25.9%), Latvia (26.8%), Slovakia (26.9%), and Hungary (29.2%).

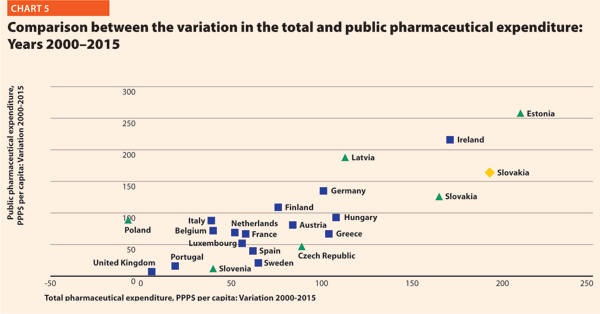

Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of pharmaceutical expenditure on total current health expenditure has generally declined in all of Europe. In 2015, the total pharmaceutical expenditure was between 342 PPP$ and 343 PPP$ per capita in Denmark and Estonia, respectively, and 766 PPP$ per capita in Germany. At least half of it was held by the public sector in all countries except Slovenia (49.5%), Denmark (43.7%), Latvia (35.0%) and Poland (34.1%). The highest values in 2015 were in Germany (82.9%), Luxembourg (80.2%), Ireland (74.6%), France (70.9%) and Slovakia (70.7%). In 2015, the pharmaceutical expenditure in PPP$ per capita held by the public sector was between 122 in Poland and 643 in Germany.

Chart 5 explores the relationship between the trend of the total and the public pharmaceutical expenditure between 2000 and 2015. In a group of outlier countries (upper right part of the chart) encompassing Estonia, Ireland, Switzerland and Slovakia, both the public and the total spending varies substantially. In Poland, the total pharmaceutical expenditure varies negatively.

In almost all EU member states, the total pharmaceutical expenditure decreased more slowly than the public pharmaceutical expenditure. This suggests that a progressively larger part of the total pharmaceutical expenditure pertains to the private sector. This shift may also indicate that the ‘willingness to pay’ and the consumption of pharmaceuticals by private owners are increasing.

Hospital capacity and delivery of care

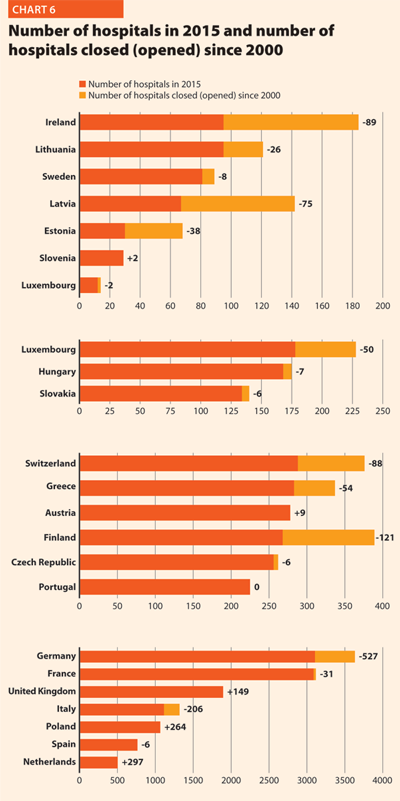

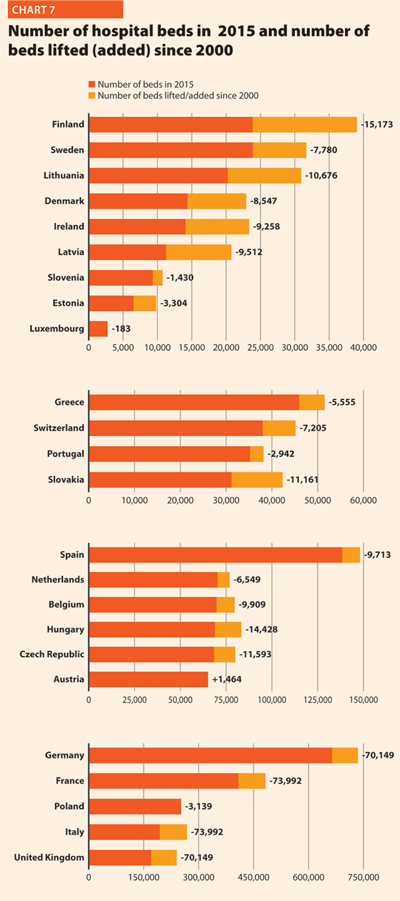

In the last 15 years health care reforms implemented all over Europe aimed at rationalising the use and provision of hospital care, improving its quality and appropriateness, and reducing its costs. The number of hospital facilities as well as the number of hospital beds dropped off on average (Charts 6 and 7). These reforms also resulted in a broad reduction of acute care admissions and length of stay, as well as in improvements in the occupancy rate of acute care beds.

During this time, almost all European countries made changes in their hospital provision patterns, and major efforts were addressed to delivering better services, increasing quality, improving efficiency and productivity. The streamlining of care delivery started from a sharp reduction in the size of secondary care institutions and moved towards more integrated and efficient patterns of care, which might result in the future in the complete overcoming of the hospital-centric model of care.

This was possible thanks to a package of financial and organisational measures addressed to improve coordination and integration between the different levels of care, increase the use of day-hospital and day-surgery and introduce new and more efficient methodologies of hospital financing in order to incentivise appropriateness (for example, the replacement of daily payments – known to encourage longer hospitalisation – by prospective payment).

In most European countries, these policies led to changes in the management of patients within hospitals and offered a possibility for reducing the number of acute care hospital beds. Only the bed occupancy rates registered more disparate trends across Europe, depending also on the demographic and epidemiological structure of population and the specific organisation of local, social and healthcare systems, that is, the structure of primary care, the presence and the efficiency of a gate-keeping system, the modality of access to secondary care, availability of home care and development of community care.

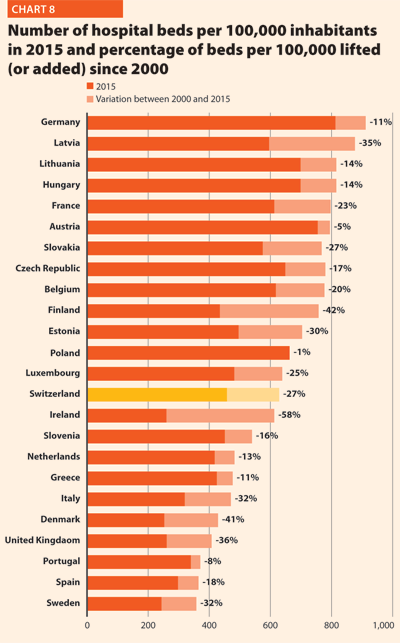

In 2015 there were, on average, 2.6 hospitals for 100,000 inhabitants, ranging from 0.9 in Sweden to 4.9 in Finland. The only European member state excluded from this range is Cyprus, where the value was approximately 9.9 in 2014. Moreover, there were on average 491 hospital beds every 100,000 inhabitants, ranging from 244 in Sweden to 813 in Germany.

Between 2000 and 2015 few changes in the number of hospitals were registered in Luxembourg (-2), Portugal (0) and Slovenia (+2).

In the same period, the total number of hospital beds per 100,000 inhabitants decreased by 23.2%, ranging from -57.6% in Ireland (which means 353 beds cut for every 100,000 inhabitants) and -0.7% in Poland (5 beds cut for every 100,000 inhabitants) (Chart 8).

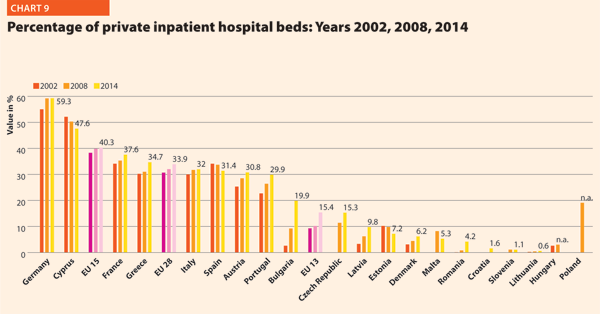

In several countries the decrease in the total number of beds was accompanied by a slight increase in the number of private inpatient beds, which are inpatient beds owned by not-for-profit and for-profit private institutions. But the share of private hospital beds – where figures are available – was still quite low in most countries, with percentages higher than 30% only in Spain (31.4%), Italy (32.0%), Greece (34.7%), France (37.7%), Cyprus (47.6%) and Germany (59.3%) (Chart 9).

Between 2000 and 2014, the number of acute hospitals decreased significantly all over Europe. A total of 357 acute care hospitals were closed in Germany, 193 in France, 170 in Italy and 122 in Switzerland.

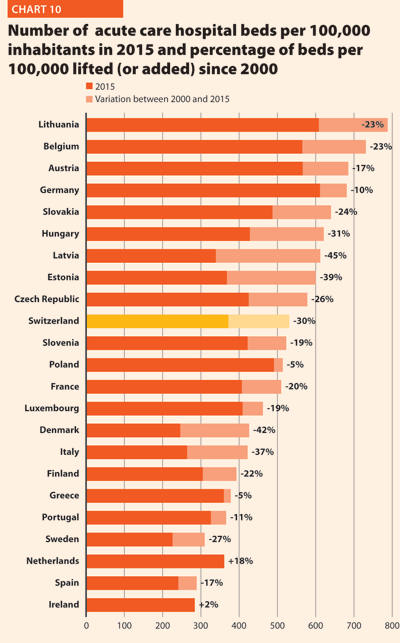

The rate of acute care hospital beds for 100,000 inhabitants in 2015 in EU ranged from 226 in Sweden to 611 in Germany. The highest figures were observable in Belgium (565), Austria (566) and Lithuania (608) while the lowest figures were in Spain (241), Denmark (246) and Italy (264).

Between 2000 and 2015, the number of acute care hospital beds per 100,000 population registered an average reduction of 20.5% in the EU. The most significant decreases were in Latvia (-44.6%), Denmark (-42.3%), Estonia (-38.7%) and Italy (-37.4%). The only exceptions were Ireland (+1.8%) and Netherlands (+18.4%) (Chart 10).

The reduction in the number of hospital beds regards especially the public providers. In the countries where data are available, this trend is associated with an increase of hospital beds in private structures. This is the case for Austria, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Latvia and Portugal. The countries that registered a decrease in both categories are the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Slovenia and Spain.

The number of acute care admissions involves the entire pathway of hospitalisation of a patient, who normally stays in hospital for at least 24 hours and then is discharged, returns home, is transferred to another facility or dies. Last data available for this figure is from 2014. The rates of acute care hospital admissions in the European countries were quite dissimilar, ranging from 7.8% in Cyprus to 24.6% in Austria.

The average length of stay measures the total number of occupied hospital bed-days, divided by the total number of admissions or discharges. In 2014, the average length of stay in acute care hospitals ranged from 5.2 bed-days in Malta to 7.6 bed-days in Germany. In Serbia, this value is 8.4 bed-days.

Between 2000 and 2015, almost all countries stabilised their rate of admissions for all hospitals. From 2000 to 2014, this figure decreased on average by 0.5 p.p. (from 17.8% to 17.3%). Most of them were also able to reduce the length of stay in acute care hospitals. Indeed, the EU average improved, decreasing from 7.6 bed-days in 2000 to 6.4 bed-days in 2014.

The link between the rate of admissions and the length of stay can be a very sensitive issue for hospitals, because it is commonly acknowledged that too short a length of stay may increase the risk of re-admissions, with a consequent waste of resources both for the hospital and for the patients and their careers. At the same time, staying too long in a hospital might indicate inappropriate settlements of patients, also causing a waste of resources.

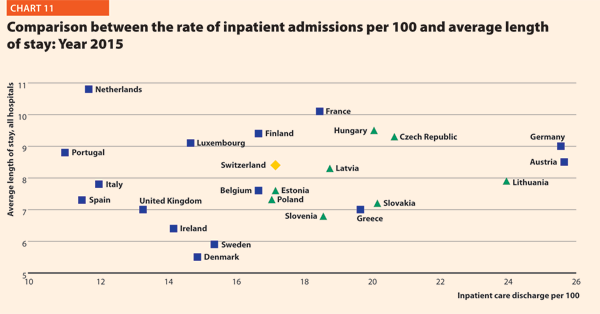

Chart 11 compares the rate of hospital admissions and the average length of stay in 2015. The last updated data shows that the average European figures corresponds to a mean rate of admissions by 17.2% and a mean length of stay of 8.0 days for all hospitals. From 2000 to 2015, the foremost variations between countries concern the admissions, ranging from 10.9 in Portugal to 25.6 in Austria. A cluster of countries, mainly encompassing EU 13, presents a number of admissions per 100 higher than the EU average (17.2%). The smallest countries seem to be more successful in finding a good balance between these two indicators.

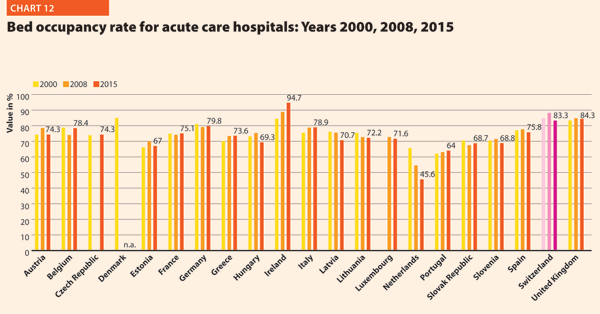

The bed occupancy rate represents the average number of days when hospital beds are occupied during the whole year and generally mirrors how intensively hospital capacity is used.

The average rate of acute bed occupancy decreased in Europe between 2000 and 2015. The reduction was between +3.4 p.p. in Greece and Italy and +0.1 in France and -5.4 and -0.4 in Latvia and Belgium. In the Netherlands, the decrease in p.p. was about 20.1. These large variations are usually due to changes in the number of admissions, average length of stay and the extent to which alternatives to full hospitalisation have been developed in each country.

Hospital and healthcare workforce

In 2015, the share of employment in the human health and social work sector on total employment in EU was on average 10.0%. Unlike in the total economy, the number of workers in this sector had been steadily growing and showed an increase even during the crisis years. Furthermore, the health and social services sector, composed of human health, residential care and social work, has an important economic weight as it generates around 7.0% of the total economic output in the EU 28 and appears to have suffered from the crisis according to the European Commission supplement to the quarterly review on “Health and social services from an employment and economic perspective” (December 2014).

The review also underlines that the health and social services sector is facing several challenges due to the fact that the workforce is ageing faster than in other sectors. Indeed, the vast majority of the people working in human health and social sector belong to the age group 25–49 years, while the share of people above 50 years increased from approximately 27% to 32% between 2008 and 2013 in EU 28. Moreover, there are large imbalances in skills levels and working patterns and recruitment and retention are conditioned by demanding working conditions. The financial constraints in most European countries are leading to a decrease in the resources available for healthcare professionals, reducing the possibilities of hiring new staff. Additionally, several countries, especially in central and eastern Europe, are experiencing migrations of their healthcare workforce.

These trends are likely to have major impacts on the hospital sector, because inpatient care alone absorbs about a third of the healthcare resources and because the hospital sector gives work to more than half of active physicians. In 2014, the total hospital employment per 100,000 inhabitants was 1506 people in EU 28, whereas in EU 15 and EU 13, this value was 1589 and 988, respectively. European countries, European organisations and EU institutions are discussing possible impacts and achievable solutions to these issues. Interestingly, several countries are shifting competences from doctors to nurses, creating new educational pathways and bachelor degrees addressed to nurses. In many cases nurses and general practitioners acquire new skills and competencies, relieving the burden of hospital care by enforcing primary care institutions and community services.

In 2014, EU15 had 359 practising physicians and 943 practising nurses per 100,000 inhabitants and EU13 had 284 physicians and 577 nurses per 100,000 inhabitants.

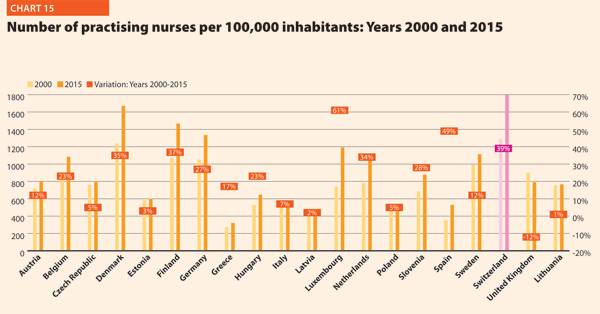

In 2015, the share of practising nurses per 100,000 registered the lowest values in Greece (321), Latvia (468), Poland (520), Spain (529) and Italy (544). The highest values belong to Germany (1,334), Finland (1,466), Denmark (1,670) and Switzerland (1,795). In the same year, the lowest share of practising physicians was registered in Poland (233), United Kingdom (279), Slovenia (283), Ireland (288), Luxembourg (291) whereas the highest values were in Germany (414), Sweden (419), Switzerland (420), Lithuania (434) and Austria (510). Between 2000 and 2015, the number of both practisng nurses and physicians increased by 20% in the EU, according to information available.

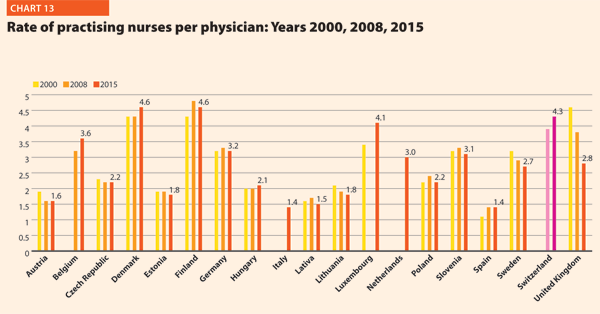

These figures provide evidence of the policies implemented, or at least the trends for the management of healthcare professionals, especially concerning the allocation of resources and responsibilities between doctors and nurses. In the EU, the average rate of nurses per physicians is about 2.1 points. In 2015 the highest values were in Luxembourg (4.1), Switzerland (4.3), Denmark (4.6) and Finland (4.6). In these countries, there is a high shift of competencies from physicians to nurses. Conversely, countries where the values are lower are Spain (1.4), Italy (1.4), Latvia (1.5) and Austria (1.6).

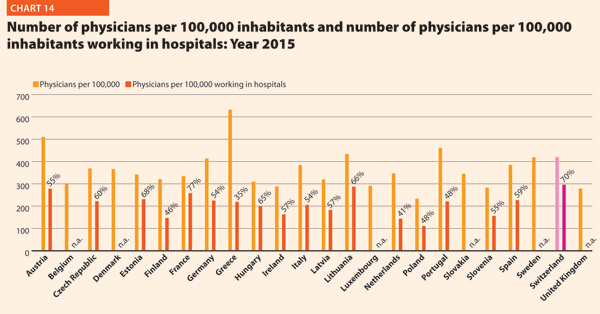

In 2015, physicians working in hospital (full or part time) were approximately 50–60% of the total, with the highest rates registered in Estonia (67.5%), Switzerland (70.5%) and France (77.2%). By contrast, the lowest values regard Greece (34.7%), the Netherlands (41.5%) and Finland (45.8%).

The most relevant positive variations on the number of physicians per 100,000 working in hospital between 2000 and 2015 were in Switzerland (+40%), Germany (+42%), Denmark (+43%) and Lithuania (+53%). By contrast, there were negative variations in Italy (-3%), Belgium (-2%) and Poland (-2%).

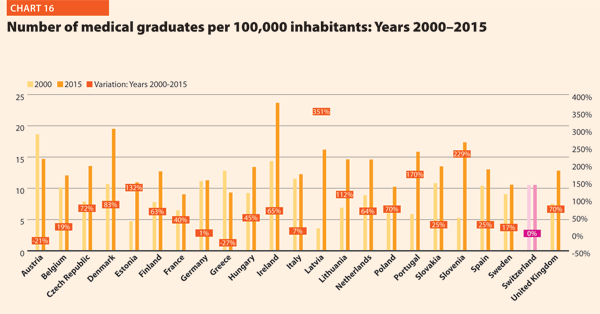

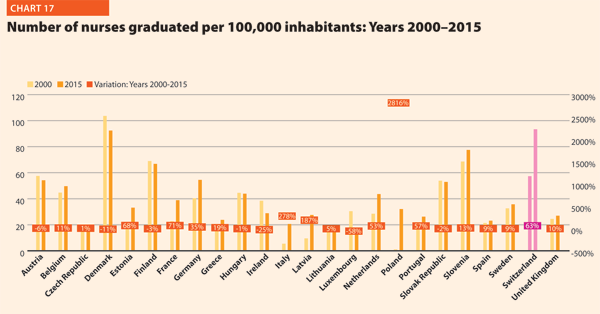

In 2015, the average number of medical and nurses graduates for every 100,000 inhabitants were respectively about 13.6 and 41.4 in the EU; however, the values across countries were quite different. The number of medical graduates per 100,000 inhabitants ranged from 9.0 and 9.3 in France and Greece to 19.5 and 23.7 in Denmark and Ireland. The number of nurses graduated per 100,000 inhabitants ranged from 12.8 and 15.8 in Luxembourg and the Czech Republic to 92.4 and 93.4 in Denmark and Switzerland.

Compared with 2000, the number of medical graduates per 100,000 inhabitants in EU registered a positive variation in the three Baltic countries (on average, around +200%), Portugal (+170%) and Slovenia (+229%). Conversely, according to data, the variation was negative in Austria (-21%) and Greece (-27%). The number of nurses graduated per 100,000 in the EU member states belonging to the OECD increased in Latvia (+187%) and Italy (+278%) and registered a remarkable positive variation in Poland (+2816%). The trend was negative in the years considered in Ireland (-25%) and Luxembourg (-58%).

References

- Despite the last update reported of Health For All Database is February 2018, some of the indicators extracted by such database have been last updated in September 2017 (Public-sector expenditure on health as % of total government expenditure, WHO estimates) and January 2018 (Private inpatient hospital beds as % of all beds).

- A System of Health Accounts 2011, Revised edition – pp. 175 & 178. OECD.

- Ibidem p. 178.