Researchers at Washington State University Health Sciences have identified a new therapeutic target for the treatment of gout.

Their study suggests that blocking a signalling molecule known as TAK1 can suppress inflammation caused by gout.

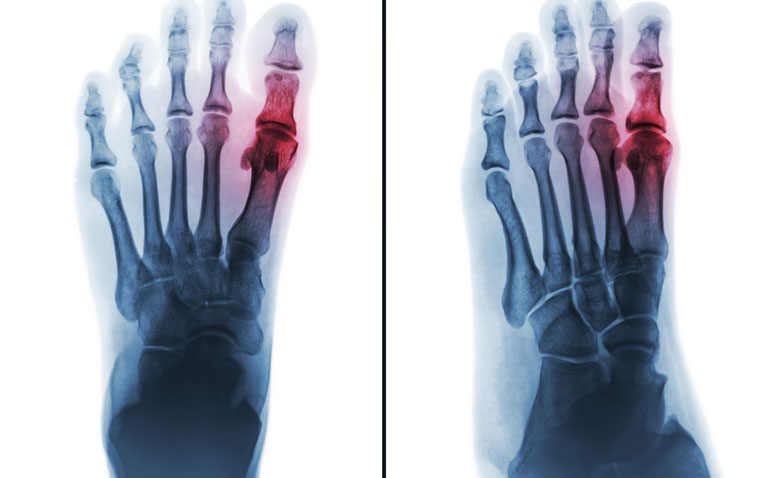

Elevated uric acid levels can lead to the formation of monosodium uric acid (MSU) crystals that accumulate in joints. In gout, the immune system will perceive these crystals as a threat and launch an immune response against them that increases the production of interleukin-1-beta (IL-1-beta), a cytokine protein that causes inflammation and triggers the intense pain and swelling people experience during gout attacks.

“It’s kind of a vicious cycle that starts with these crystals, which cause IL-1-beta to be produced, inducing inflammation and activating a lot of other proteins to produce more inflammation,” said Salah-Uddin Ahmed, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences in the WSU College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and senior author on the study.

“We already knew that MSU crystals activate what is known as the inflammasome pathway, which produces IL-1-beta,” Ahmed said. “However, our study found that MSU crystals also use an alternate pathway that triggers inflammation through TAK1, which is a new finding related to how gout develops.”

Next, they showed that the use of a chemical that inhibits, or blocks, TAK1 could completely suppress any inflammation caused by MSU crystals, both in healthy human macrophage cells and in a rodent model of gout.

Ahmed said their discovery has opened the door towards the development of new treatment strategies for gout.

One current treatment he said scientists have experimented with is Anakinra, a drug that blocks the binding of IL-1-beta to its receptor. Though it has shown promise, Ahmed said the drug is not clinically used for gout, because it is given by infusion – which requires hospitalisation; its effectiveness is limited; and it comes with a potential risk of infections when used long term. Developing TAK1 inhibitor drugs that could be taken by mouth would allow patients with gout to manage flare-ups of the disease at home.

The team’s next goal is to confirm their findings in cells taken from patients with gout. They are currently pursuing federal funding for this project, which they plan to conduct in collaboration with clinical scientists at the University of Alabama Birmingham and the University of Michigan Ann Arbor. If their findings hold up, this may eventually lead to clinical trials to test TAK1-inhibitors in patients.

Ahmed said their finding could also eventually be tested in other diseases that involve IL-1-beta mediated inflammation, such as multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and type 1 diabetes.