Delays in gut microbiome maturation in young children are uniformly associated with distinct allergic diagnoses at five years of age, according to the findings of a study by Canadian researchers.

The study, which was published in the journal Nature Communications, revealed how specific gut microbiome features and early life influences are associated with children developing any of four common allergies: atopic eczema, asthma, food allergy and/or allergic rhinitis.

It is possible, therefore, that these findings could lead to methods for predicting whether a child would develop an allergic disease. They could also form the foundation of strategies to prevent them from developing, especially given that food allergies in particular continue to be a major source of life-threatening reactions in children.

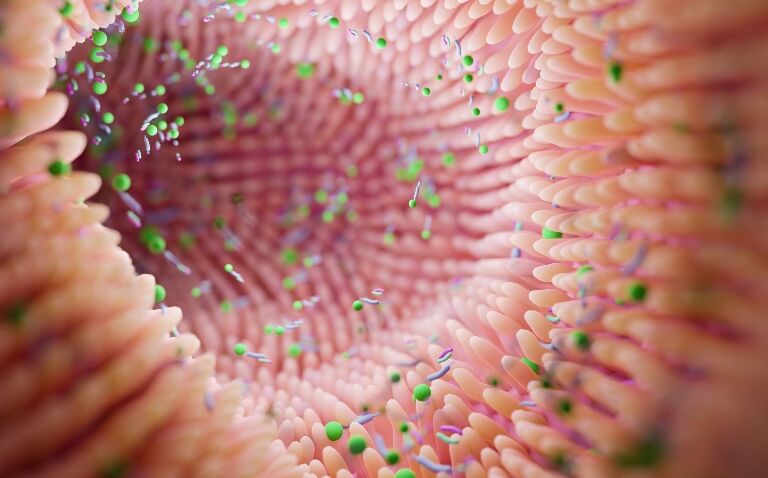

Courtney Hoskinson, PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the study‘s lead author said: ‘Typically, our bodies tolerate the millions of bacteria living in our guts because they do so many good things for our health. Some of the ways we tolerate them are by keeping a strong barrier between them and our immune cells and by limiting inflammatory signals that would call those immune cells into action.‘

‘We found a common breakdown in these mechanisms in babies prior to the development of allergies.‘

In the study, researchers evaluated the four clinically distinct allergic diseases diagnosed at five years of age in the large, deeply characterised CHILD cohort study. The team adopted a multi-omics approach to profile infant stool collected at study visits scheduled for ages three months and one year.

Gut microbiome and allergic diseases

The study used a deeply phenotyped cohort of 1,115 children. A total of 523 participants could be defined as a ‘healthy‘ control group in that they did not develop allergic sensitisation at any time in their life up to five years of age.

Some 592 children had been diagnosed by an expert physician at the five-year scheduled visit with one or more allergic disorders: atopic eczema (n = 367), asthma (n = 165), food allergy (n = 136) and allergic rhinitis (n = 187). There were gut microbiome features uniformly associated with these allergic diagnoses at five years of age.

When evaluating the association between early-life factors and a diagnosis of allergic disease at age five, male sex, a history of either maternal of paternal atopy and antibiotic usage before age one were all significantly linked with an increased risk of developing an allergic disease.

In contrast, breastfeeding up to age six months and self-identifying as Caucasian were negatively associated with an allergy diagnosis.

Dr Stuart Turvey, professor in the department of pediatrics at UBC, investigator at British Columbia Children‘s Hospital Research Institute and co-senior author on the study, added: ‘There are a lot of potential insights from this robust analysis. From these data we can see that factors such as antibiotic usage in the first year of life are more likely to result in later allergic disorders, while breastfeeding for the first six months is protective. This was universal to all the allergic disorders we studied.

‘Developing therapies that change these interactions during infancy may therefore prevent the development of all sorts of allergic diseases in childhood, which often last a lifetime.‘