A major clinical trial has shown some men with advanced prostate cancer who have exhausted all other treatment options could live for two years or more on immunotherapy.

The Phase II clinical trial was led globally by a team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden Foundation Trust, and involved 258 men with advanced prostate cancer who had previously been treated and become resistant to androgen deprivation therapy and docetaxel chemotherapy.

The study has been published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and was funded by the drug’s manufacturer Merck, Sharpe & Dohme.

Researchers found that a small proportion of men were ‘super responders’ and were alive and well even after the trial had ended despite having had a very poor prognosis before treatment.

The study found that one in 20 men with end-stage prostate cancer responded to the immunotherapy pembrolizumab – but although the number who benefited was small, these patients sometimes gained years of extra life.

The most dramatic responses came in patients whose tumours had mutations in genes involved in repairing DNA, and the researchers are investigating whether this group might especially benefit from immunotherapy.

Overall, 5% of men treated with pembrolizumab saw their tumours actually shrink or disappear, while a larger group of 19% had some evidence of tumour response with a decrease in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level.

Among a group of 166 patients with particularly advanced disease and high levels of PSA, the average length of survival was 8.1 months with pembrolizumab.

Nine of these patients saw their disease disappear or partly disappear on scans. And of these, four were super-responders who remained on treatment at the end of study follow-up, with responses lasting for at least 22 months.

A second group of patients whose PSA levels were lower but whose disease had spread to the bone lived for an average of 14.1 months on pembrolizumab.

New larger trials are now under way to test whether men with DNA repair gene mutations in their tumours, or those whose cancer has spread to the bone, should receive pembrolizumab as part of their care.

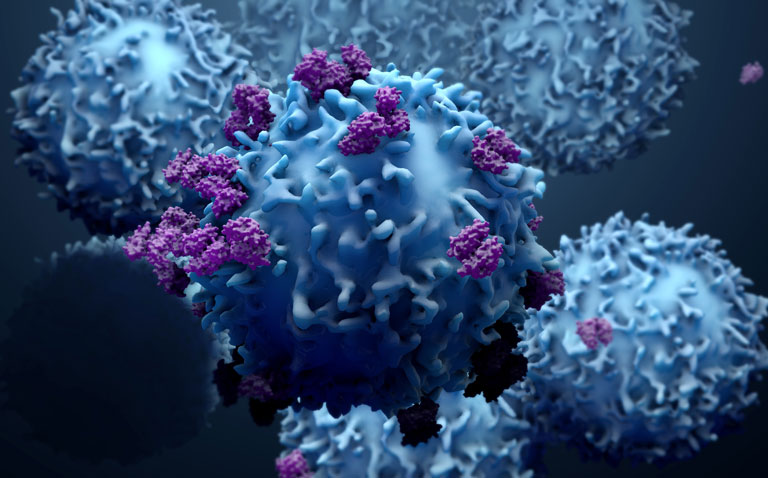

The study also compared the effectiveness of pembrolizumab in men whose tumours had a protein called PD-L1 on the surface of their cancer cells and those whose tumours did not. Targeting PD-L1 activity with pembrolizumab takes the ‘brakes’ off the immune system, setting it free to attack cancer cells.

But the study found that testing for PD-L1 was not sufficient to tell which patients would respond to treatment. Men with PD-L1 in their tumours survived 9.5 months compared with 7.9 months for patients without PD-L1 in their tumours.

Identifying better tests to pick out who will respond best will be critical if pembrolizumab is to become a standard part of prostate cancer treatment.

Pembrolizumab was well tolerated, with 60% of patients reporting any side effects and only 15% of patients experiencing grade 3-5 side effects.

Professor Johann de Bono, Regius Professor of Cancer Research at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said: “Our study has shown that a small proportion of men with very advanced prostate cancer are super responders to immunotherapy and could live for at least two years and possibly considerably longer.

“We don’t see much activity from the immune system in prostate tumours, so many oncologists thought immunotherapy wouldn’t work for this cancer type. But our study shows that a small proportion of men with end-stage cancer do respond, and crucially that some of these men do very well indeed.

“We found that men with mutations in DNA repair genes respond especially well to immunotherapy, including two of my own patients who have now been on the drug for more than two years. I am now leading a larger-scale trial specifically for this group of patients and am excited to see the results.”

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “Immunotherapy has had tremendous benefits for some cancer patients and it’s fantastic news that even in prostate cancer, where we don’t see much immune activity, a proportion of men are responding well to treatment.

“A limitation with immunotherapy is that there’s no good test to pick out those who are most likely to respond. It’s encouraging to see testing for DNA repair mutations may identify some patients who are more likely to respond, and I’m keen to see how the new, larger trial in this group of patients plays out.”