Penicillin allergy is a common concern in healthcare settings, impacting patient safety, antimicrobial stewardship and successful infection treatment. Gerry Hughes explores the epidemiology of penicillin allergy and its significance in the context of patient care, as well as the need for a system-wide and multidisciplinary approach to penicillin allergy delabelling.

Penicillin is commonly implicated in drug hypersensitivity. In developed countries, between five and 15% patients carry a penicillin allergy label, and patients receive a penicillin allergy label by their third birthday in approximately 75% of cases.

However, a large body of evidence suggests upwards of 90% of patients with a penicillin allergy label are not truly allergic. In England alone, 5.9% of the population are designated penicillin allergic, with an estimated 2.7 million of these being incorrectly labelled as such.

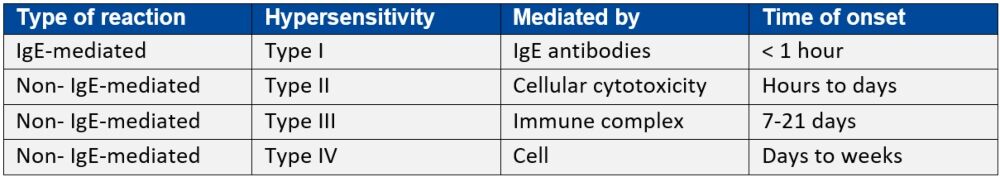

It is important for patients and patient carers to know that common antibiotic adverse events, such as upset stomach, vomiting or diarrhoea are not symptoms of penicillin allergy. The Gell and Coombes classification of drug hypersensitivity (see Table 1 below) provides a useful reference for assessing and diagnosing drug-induced allergic reactions.

Hypersensitivity reactions associated with penicillin are predominantly Type I (anaphylactic, immediate onset) or Type IV (cell-mediated, delayed skin reactions).

Given the prevalence and implications of incorrect penicillin allergy labels, it is important for healthcare professionals to understand the impact of this issue on the successful treatment of infections and the broader implications for antimicrobial stewardship (AMS).

Table 1: Gell and Coombes hypersensitivity classification*

IgE: immunoglobulin E

*Adapted from Penicillin allergy: A practical guide for clinicians

Penicillin and successful infection treatment

Inappropriate labelling of penicillin allergy negatively impacts on patient care for several reasons. For many infections, penicillin, or beta-lactam antibiotics, are first choice therapy due to the weight of evidence behind their effectiveness.

Penicillin avoidance, due to a spurious penicillin allergy designation, can lead to use of less effective antibiotic regimens, unnecessary exposure to alternative antibiotic therapy, development of Clostridium difficile infection, additional time required in hospital and increased overall care costs.

The UK Health Security Agency’s ‘Start smart then focus’ AMS toolkit – first published in 2011 and most recently updated in September 2023 – makes evidence-based recommendations on effective AMS practices in hospitals, including appropriate management of penicillin allergy labels.

The toolkit advises secondary care clinicians and leaders about how local AMS policies and guidelines should include assessment of reported drug allergies and encourages them to conduct allergy delabelling where possible ‘to ensure patients are not denied access to the most effective therapy’.

Penicillin allergy assessment and delabelling (PAD) seeks to investigate a penicillin allergy history, remove the allergy designation where possible and/or desensitise the patient to future penicillin therapies.

Although immunology specialists are well-suited to develop and conduct PAD, it is a role often lacking in hospitals and other clinical environments. The British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology states that PAD performed by allergy specialists only, ‘cannot meet either current or future demand’.

Indeed, a recent study published in the Journal of Infection suggested that inaccurate penicillin allergy labels are magnified by insufficient allergy specialists. It investigated the feasibility of a direct oral penicillin challenge in delabelling low-risk patients with penicillin allergy by non-allergy healthcare professionals.

Multidisciplinary innovations in PAD

PAD is an evidence-based component of AMS and has previously demonstrated benefits in optimising antimicrobial choice and allowing for cost-effective treatment choices.

This evidence base extends to a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to PAD, which harnesses the expertise of infection specialists from medicine, pharmacy and nursing, amongst others.

An excellent example of this MDT strategy is the PAD toolkit developed by the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG). This suite of resources is for non-allergy specialists to aid removal of penicillin allergy labels from patients with unverified allergic reactions, including resources for primary care practitioners and patients.

Professor Andrew Seaton, consultant in infectious diseases and general medicine at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde in Scotland, is chair of SAPG and recognises the importance of these guidelines in practice.

‘Whilst removing an allergy label sounds easy to do, it is difficult to do safely and sustainably without a formal structure,’ he says. ‘The SAPG toolkit has been a collaborative, multidisciplinary development which provides that structure and assurance for both clinicians and patients.’

St James’s Hospital (SJH) in Dublin, Ireland, provides such MDT-led PAD services, led by Professor Niall Conlon, consultant clinical immunologist and professor of clinical immunology at Trinity College Dublin.

Echoing Professor Seaton’s comments, Professor Conlon notes that successful PAD programmes require a systems-level approach. He underlines the need for an adequately resourced service, underpinned by commensurate education and training for the MDT involved. ‘A cohesive strategy is needed where all clinicians, not just allergy specialists, feel comfortable performing delabelling,’ he says.

In line with SAPG recommendations, SJH also provides resources to patients on penicillin allergy, including information on confirmed penicillin allergy.

Facilitators and barriers

Neil Powell, consultant antimicrobial pharmacist and associate director, antimicrobial stewardship at Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust in England, is the recipient of a clinical academic grant from the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

His research work focuses on removing erroneous penicillin allergy labels and leveraging an MDT approach to achieve that. He is currently developing a complex intervention that will facilitate PAD to be delivered by ward pharmacists and ward doctors.

Describing his work, he says: ‘This will enable penicillin allergy delabelling to be delivered to more patients across the hospital, with appropriate governance frameworks to ensure it is done safely.’

As part of Mr Powell’s research, a recent qualitative assessment of PAD facilitators and barriers found broad support among healthcare workers for an MDT approach. Driven by a desire to ensure patient safety, participants felt that PAD should be a multidisciplinary responsibility, shared between doctors and pharmacists and supported by pharmacy technicians and nurses.

However, the study also found that patient engagement and education on the topic was key. As with all healthcare interventions, participants also recognised the need for an evidence-based service, with sufficient resources to support its aims and objectives.

Mr Powell says: ‘From the qualitative studies I have done, healthcare workers have said that it needs to be a shared responsibility, not the responsibility of one specialty.’ In particular, he notes that ward pharmacists are well placed, as experts in medication safety and medication optimisation, to support and deliver PAD.

In fact, in September 2023, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) launched a new checklist for pharmacists and pharmacy teams to help inform conversations with patients about penicillin allergy and determine their true status.

The checklist states that on admission to hospital pharmacy professionals should ensure allergy history is reviewed as part of the drug history and medicines reconciliation process. It also refers to guidance on setting up non-specialist allergy delabelling services in hospitals from the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Primary care and penicillin allergy delabelling

PAD may also have a place beyond secondary care settings, and this goes further than simply providing education to primary care practitioners.

The RPS checklist, for instance, encourages GP practice pharmacy teams can run searches to identify any patients with a documented allergy that have since received penicillin and ensure their records are updated to reflect this.

The ALlergy AntiBiotics And Microbial resistAnce (ALABAMA) trial, based in the UK, aims to determine if a primary care penicillin allergy assessment package is safe and effective in improving patient health outcomes and antibiotic prescribing.

This multicentre, parallel-arm, open-label, randomised pragmatic trial aimed to recruit between 656 and 848 participants from participating NHS general practices in England. Recruitment was completed in 2023 and results are expected this coming autumn.

Recognising the potential to expand PAD to community settings, Professor Seaton highlights the continued need for collaboration. ‘If we can scale up [PAD] we can expand initiatives beyond secondary care and into the community. Undoubtedly a multidisciplinary approach is needed, [and] involvement of clinical pharmacists and specialist nurses will be crucial.’

It’s clear that penicillin allergy delabelling is an essential component of AMS, with important implications for patient care and public health. More work is required to educate healthcare professionals across sectors, as well as the public, on the prevalence and consequences of inaccurate penicillin allergy labels, but work is underway to support this across the UK and in Europe.

Ultimately, development of well-resourced MDTs and evidence-based guidelines will facilitate a safe and effective delabelling process, ensuring that patients receive the most appropriate treatment for their condition, all while minimising the risk of adverse reactions and keeping patients safe.