With lack of time often cited as a barrier to undertaking physical activity, cramming a week‘s worth of exercise into a day or two may seem more achievable, especially if it provides comparable cardiovascular benefits to a more evenly distributed pattern. Hospital Healthcare Europe‘s clinical writer and resident pharmacist Rod Tucker considers the evidence.

It is abundantly clear that being physically active is associated with health benefits. Current guidance on physical activity for adults in most major countries in Europe is broadly similar: undertake either at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity a week or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity, plus two days a week of strengthening activities to work all of the main muscle groups.

Moreover, it is advocated that exercise is undertaken every day or spread evenly over four to five days a week.

But is there any evidence that achieving this amount of exercise is associated with health benefits? In a 2020 study, an international research group tried to answer this question.

The team looked at the association between attainment of the recommended amount of physical activity among a representative sample of US citizens, and all-cause and cause specific mortality.

Their analysis included 479,856 adults who were followed for a median of 8.75 years. The findings were very clear: undertaking the recommended amounts of physical activity reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 40%. But not only that, such levels of activity lowered the risk of cardiovascular disease by 50% and the risk of cancer by 40%.

With clear evidence of the health benefits from undertaking the recommended levels of physical activity, surveys have also identified some notable and recognised barriers to exercising. One of the most consistently reported barriers is sufficient time to exercise, and this is seen irrespective of age and gender.

Compressing the time for exercise

Although healthcare professionals may advocate that their patients engage in exercise as part of the health promotion message, it seems they don‘t always practise what they preach. In fact, research shows that lack of time is also a perceived barrier to exercise among doctors and nurses.

As well as insufficient time, a demanding workload gives rise to high levels of burnout and stress, and changing shift patterns can limit time and motivation, which all represent additional barriers to exercising among clinicians.

Evidence suggests that exercising for just one or two days a week could accrue the same health benefits seen among those who exercise more regularly throughout the week. For example, so-called ‘weekend warriors‘ – those who restrict physical activity to just one or two sessions per week – have a similar level of all-cause mortality compared to those who spread their physical activity over several days.

In fact, a 2023 meta-analysis of four studies with 426,428 participants found that the risk of both cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality in those compressing their activity into two days was 27% and 17% lower, respectively, when compared to those who were inactive.

However, a limitation of this analysis was that levels of physical activity were self-reported and therefore prone to misclassification bias.

Weekend warrior activity and health outcomes

With inherent self-reporting bias an issue, a recent study examined the value of accelerometer-derived data. Researchers recently set out to examine the association between a weekend warrior pattern of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) achieved over just one to two days, compared to the activity being spread more evenly, with the risk of incident cardiovascular events.

The researchers retrospectively analysed a UK Biobank cohort who provided a full week‘s worth of wrist-based accelerometer physical activity data. Individuals were classified into three groups: active weekend warriors, in which more than half of their total MVPA was undertaken over one to two days; regularly active, where exercising was spread throughout the week; and inactive, where less than 150 minutes of MVPA per week was undertaken.

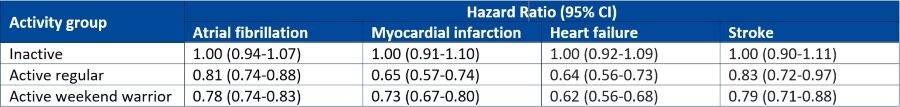

They looked at associations between the different activity pattern and cardiovascular outcomes such as incident atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke. The findings were then adjusted for several potential covariates including age, sex, ethnicity race, alcohol and smoking and diet quality.

Data for 89,573 individuals with a mean of 62 years (56% female) were included in the analysis and who were followed for a median of 6.3 years. Interestingly, when stratified at the threshold of 150 minutes or more of MVPA per week, nearly half of the entire cohort (42.2%) were classed as weekend warriors.

The findings for atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke are summarised in the table below.

Just keep moving

The accelerometer-derived study shows that engagement in physical activity, regardless of the pattern, is able to reduce the risk of a broad range of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, although many healthcare professionals‘ working weeks may not permit specific exercising days, it seems that compressing physical activity into just two days per week, wherever possible, still achieves comparable health benefits.

So, whether it’s advice for patients or the foundation for personal fitness goals, the key message is to just keep moving.