A recent multidisciplinary report concluded that significant gaps currently exist in consistent education and training on fluid management, and innovative solutions are needed to drive change and transformation.1 Healthcare institutions should therefore implement programmes on fluid stewardship to achieve their quality improvement and patient safety goals.

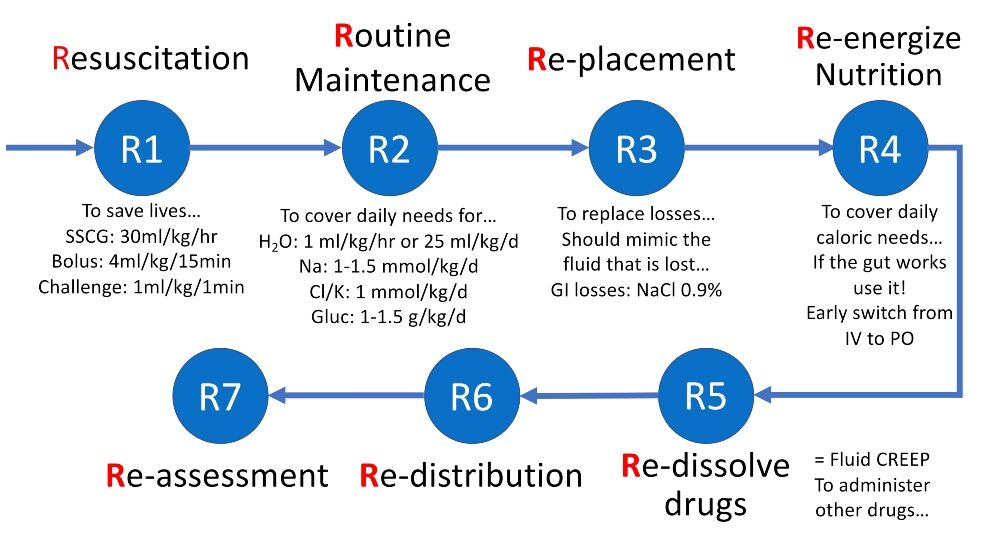

The fundamental concept of intravenous (IV) fluid therapy is to ‘restore and maintain tissue oxygen, fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, and central euvolaemia’.2 This should be combined with an understanding of proper fluid management goals in resuscitation, replacement, nutrition, dilution (for other medications) and maintenance settings – see Figure 1.

Figure 1. The 7 Rs framework with the five indications for fluid administration (resuscitation, routine maintenance, replacement, dilution or nutrition)

Cl: chloride; GI: gastrointestinal; Gluc: glucose; H2O: water; IV: intravenous; K: potassium; Na: sodium; PO: per os; SSCG: Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence fluid guidelines provide a good starting point3 for fluid stewardship interventions, and these should include:

- An understanding of the physiology of water and electrolyte homeostasis

- Knowledge of the risks, benefits and harms of IV fluids

- Assessment of fluid and electrolyte needs

- Assessment of fluid and volume status and fluid (un)responsiveness

- Prescribing IV fluids properly to each patient

- Evaluating and documenting changes

- Monitoring the response to IV fluids

- Taking further action as required

- Reporting complications of fluid management or administration as incidents that require investigation, to provide a basis for learning and improvement.

Improving education and training for fluid management

When implementing effective fluid stewardship, it is essential to provide a platform that meets the needs of all healthcare practitioners at all stages of their careers.

In previous questionnaire-based analyses of clinicians responsible for fluid management – and with experience levels ranging from trainees to experienced clinicians – fluid management knowledge scores were low, and most participants reported having experienced unreported fluid-related serious adverse events.4,5

To reach all clinicians involved in fluid management with education and training based on evidence-based medicine and guidelines, educators should abandon old ideas that are often based in silo thinking and understand the value of a systems approach to education that improves patient care.

A systems approach recognises the roles that all specialties play in patient care and encourages open communication that avoids practices that unnecessarily separate different aspects of the fluid management team into independent parts.1

To achieve this systems approach goal, and to maximise staff involvement from all relevant specialties involved in fluid management, effective training should take advantage of a variety of innovative educational resources.

Better education and training require a transformation in mindset and behaviour among both junior and established clinicians. It is important to identify fluid stewards and institutional ambassadors who support not only staff education but also change, and who can obtain the necessary buy-in from hospital administrators, such as medical and nursing directors.

Innovative virtual learning platforms should be considered for staff convenience and flexibility. Targeted education should be provided to all staff responsible for fluid management decisions.

Guidelines, KPIs and data

Guidelines are valuable tools to ensure consistent fluid delivery practices after regular staff education is established. Any proposed local guideline should include assessment, prescription, monitoring, fluid balance charting and regular review of clinical status.

To facilitate the implementation of fluid stewardship programmes, it is important to analyse the local hospital situation regarding fluid delivery and consumption and the calculation of some common key performance indicators (KPIs) such as the total amount of fluids per patient and occupied bed days.

For isotonic resuscitation fluids, the ratio between balanced and unbalanced (abnormal saline) fluids could be prospectively monitored. For maintenance, the ratio between hypotonic balanced maintenance versus other glucose-containing solutions could be monitored.

Poor fluid management might not directly result in mortality but can impact clinically relevant outcomes such as acid-base and electrolyte disturbances, fluid accumulation (syndrome) and acute kidney injury, which, in turn, might contribute to morbidity and mortality.6

Studies have shown that about one patient in five will suffer from deleterious consequences of inappropriate fluid management; this can be related to too little or too much fluid.

Considering the risk of poor outcomes, institutions need to analyse the potential cost benefits of good fluid stewardship. To achieve this, institutions will need to rely on big data strategies derived from available data sources as opposed to snapshots of local data.

These data sources already exist and include prescription data, laboratory records, imaging results and patient admission and discharge information.

Real-world data and machine learning

In the meantime, without robust data on complication rates, a real cost-effectiveness analysis might be extremely challenging, and the best approach that can be applied is to monitor fluid (mis)use and outcomes in specific hospitals.

One such example of real-world data is the European Health Data & Evidence Network (EHDEN) project, which aimed to collect Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership-Common Data Model (OMOP-CDM) compatible data from 100 million patient records and has now collected data on 236 million patient records.

Developing machine learning models that consider costs, outcomes and long-term implications of different fluid management approaches can assist in decision-making and resource allocation and could result in potential cost savings associated with implementing evidence-based fluid management practices.

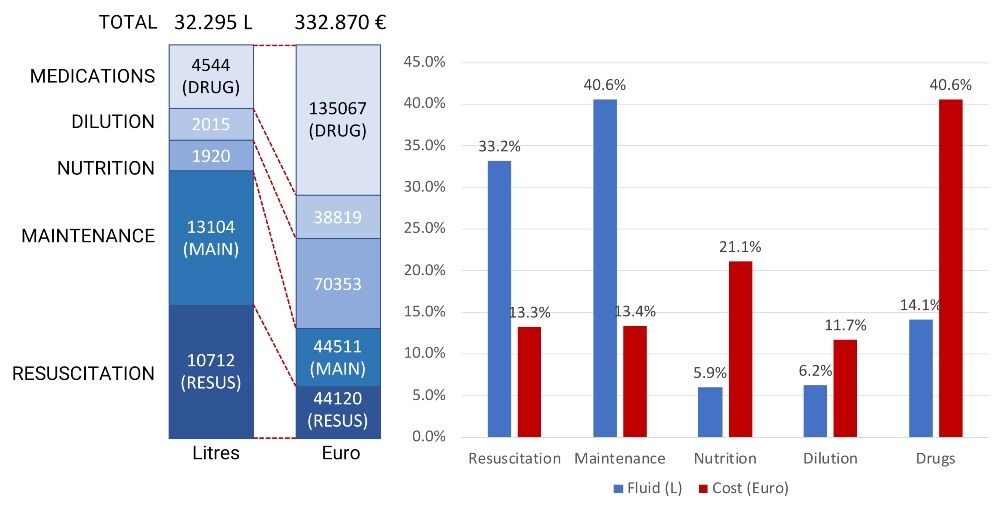

Figure 2 illustrates how OMOP-CDM can help to analyse annual fluid consumption and associated costs. In this case, the annual cost savings could mount up to approximately €38,000 and €42,000 depending on a reduction in total fluid consumption to 4 L and 3 L per stay, respectively.

Figure 2. Annual total consumption and cost of intravenous fluids and drugs in a medium-sized hospital (250 beds)

Resuscitation = isotonic fluids; maintenance = glucose-containing fluids; drug dilution = small 50- or 100-ml fluid bags.

Data analysis undertaken with ’hospi-intelligence’, which was developed by Medaman, via OMOP-CDM showed that fluid overuse was present in 20% of cases. This is defined as more than 6 L per patient stay and more than 0.6 L per bed occupying day.

Assuming that drugs and nutrition cannot be omitted, a potential cost reduction can come from stopping maintenance and reducing isotonic fluids as well as further concentration of drug dilution.

Effective institutional fluid stewardship

The practice scope of healthcare providers involved in fluid management varies widely, from the complicated and risky administration and monitoring of fluids in the critical care setting to procurement, quality improvement and evidence-based research projects.

Monitoring daily and cumulative fluid balance is an integral component of fluid therapy and good patient care; it can identify potential problems and allow for earlier escalation when required.

A trigger point on a fluid balance chart that supports fluid delivery decision-making is important for the identification of suboptimal or increased fluid intake or output.

These trigger points should be highlighted in an institution-specific educational programme that emphasises the importance of early warning scores and strategies for an appropriate response.

Patient information leaflets encourage patients and their relatives to be aware of their fluid needs and explain IV therapy. Self-monitoring of intake is possible for some patients.

A consistent approach to teaching fluid therapy based on established guidelines, as well as implementation of fluid stewardship, should help reduce prescriber confusion when faced with the need to prescribe fluids in different patient scenarios.

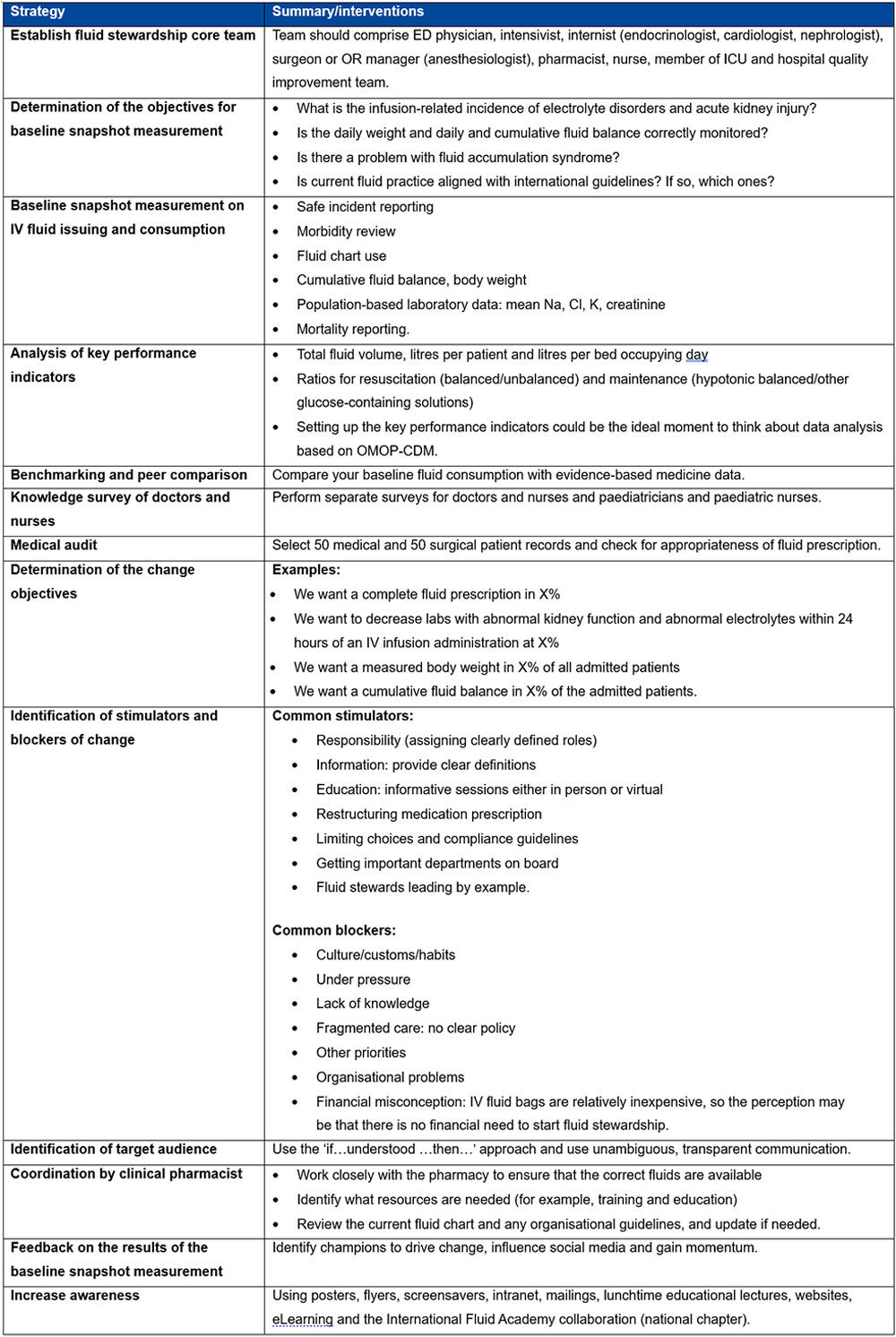

All institutions should consider a commitment to effective fluid stewardship at the local level. Institutions that have yet to implement standardised fluid stewardship can follow some key steps for success, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Strategies to achieve institutional best practices in fluid stewardship*

*Figure 3 adapted with permission from Malbrain MLNG et al. according to the Open Access CC BY licence 4.0.1

Once fluid stewardship is implemented, metrics for recording staff education should include the number of learners taught and accessing e-learning modules, assessment results, and ultimately whether prescribers are following guidelines, as determined by information from snapshot audits and fluid usage data. Strategies are discussed in Table 1.

Table 1. Strategies to engage clinical leads with the implementation of a fluid stewardship programme**

**Table 1 adapted with permission from Malbrain MLNG et al. according to the Open Access CC BY licence 4.0.1

Best practices for fluid stewardship

For the attending clinician, the process of fluid prescription can be condensed to four questions:

- Does my patient need fluid, and is there a potential benefit of fluid administration?

Remember that the best fluid may be the one that has not been administered unnecessarily. - If so, why?

This question considers whether it is for maintenance, replacement of losses, or resuscitation, or if the patient requires fluid restriction? Is there body compartment fluid redistribution? - Which fluid should be used in these differing scenarios?

- How much should I give to the patient, when and for how long?

This question considers the dosing, rate, speed, timing, duration and route of administration.

After starting an IV fluid, the next four questions that should be addressed are:6

- When to stop IV fluids? When shock has been resolved

This question addresses the risks of ongoing fluid administration - When to start fluid de-escalation?

(E.g. when to stop maintenance fluids or when to start hypercaloric enteral feeding to reduce fluid intake and the risk of fluid accumulation) - When to start active fluid removal or deresuscitation?

When the presence of fluid accumulation or global increased permeability syndrome negatively impacts end-organ function.

This question addresses the benefits of fluid removal (e.g. improvement of pulmonary oedema) - When to stop fluid removal?

This question addresses the risks of fluid removal (e.g. causing hypoperfusion).

To expand on these questions, the ‘Five Ps’ of effective fluid prescriptions should be considered:

- Physician: All starts with the physician’s participation in making decisions related to fluid management

- Prescription: The physician should engage in writing a prescription that accounts for drug, dose, duration and, whenever possible, de-escalation

- Pharmacy: The prescription is sent to the pharmacy and is checked for inconsistencies by the pharmacist to get a more holistic view

- Preparation: The process by which the prescription is prepared and additions (e.g. electrolytes) made

- Patient: The filled prescription goes back to the patient and fluid stewards should observe administration, response and debrief.

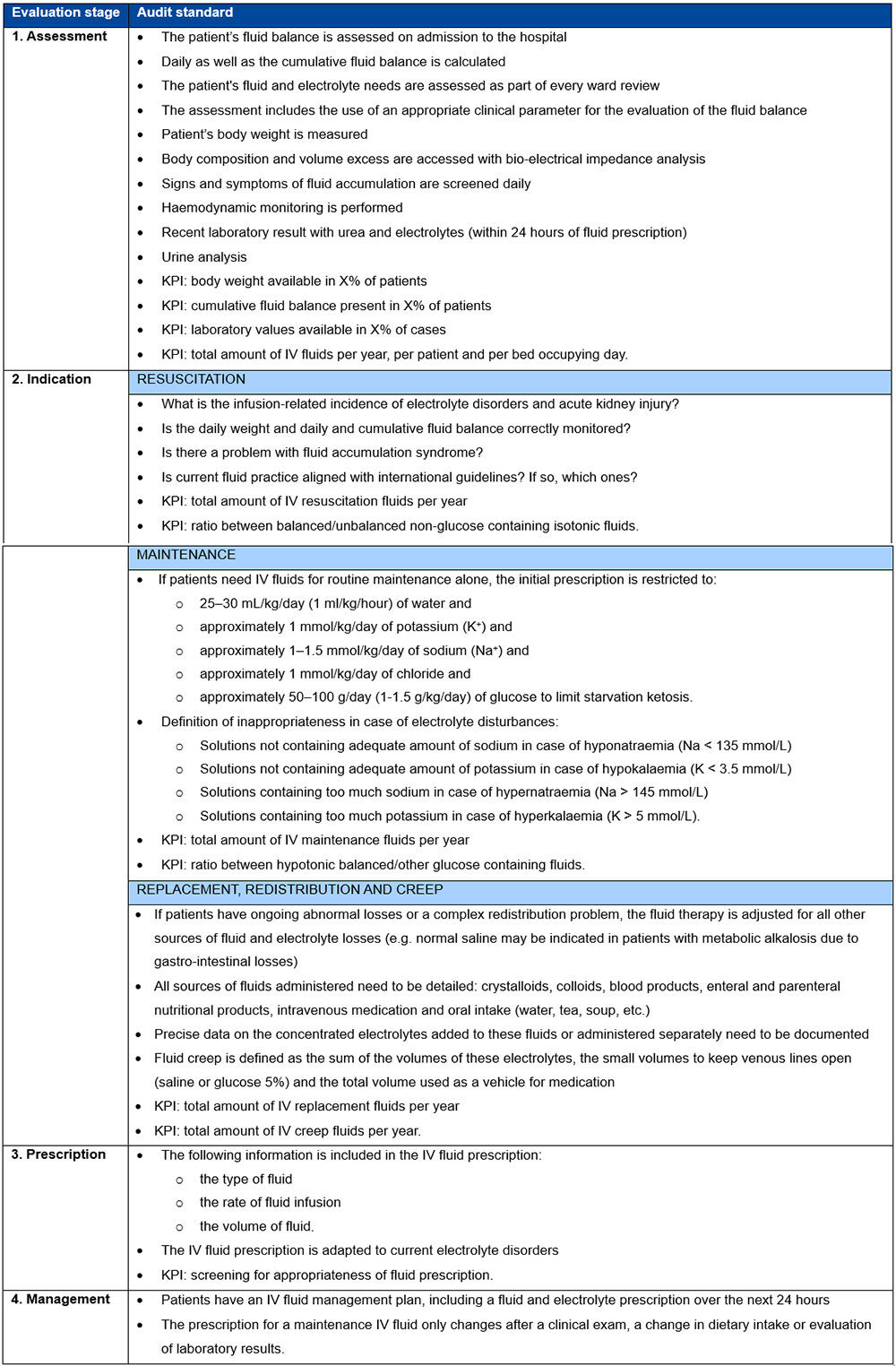

Finally, all staff responsible for fluid management should regularly monitor patients for the appropriateness of fluid prescriptions, including initial patient assessment, decisions on fluid indication, fluid prescription and regular fluid management. The stages for checking on the appropriateness of IV fluid therapy are summarised in Table 2.7

Table 2. Four stages of monitoring the appropriateness of fluid prescription at the bedside***

***Table 2 adapted with permission from Malbrain et al.7

Conclusion

The implementation of effective fluid stewardship programmes in healthcare is of paramount importance, and these should involve coordinated interventions to optimise fluid therapy for the best clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness and prevention of adverse events.8

Guidelines exist to standardise fluid management, and it is essential to identify effective fluid stewards in every hospital ward to ensure consistency.9 Data can be used for support and training and clinical outcomes can demonstrate the value of proper fluid prescription.

The message urges immediate implementation of fluid stewardship in hospitals and stresses the need for education and training to bridge practice gaps and improve patient outcomes.

Authors

Manu Malbrain

First Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, Medical University of Lublin, Poland; Medical Data Management, Medaman, Geel, Belgium; International Fluid Academy, Lovenjoel, Belgium

Dries Tant

Medical Data Management, Medaman, Geel, Belgium

Geert Byttebier

Medical Data Management, Medaman, Geel, Belgium; Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Marc Lamont

Medical Data Management, Medaman, Geel, Belgium

Luc Belmans

Medical Data Management, Medaman, Geel, Belgium

References

- Malbrain MLNG et al. Multidisciplinary expert panel report on fluid stewardship: perspectives and practice. Ann Intensive Care 2023 Sep 25;13(1):89

- Miller TE, Myles PS. Perioperative fluid therapy for major surgery. Anesthesiology 2019;130(5):825–32

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Intravenous fluid therapy in adults in hospital: clinical guideline CG174. [Last accessed January 2024]

- Leach R et al. Fluid management knowledge in hospital physicians: “Greenshoots” of improvement but still a cause for concern. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20(3):e26–31

- Nasa P et al. Intravenous fluid therapy in perioperative and critical care setting-Knowledge test and practice: An international cross-sectional survey. J Crit Care 2022 Oct;71:154122

- Malbrain MLNG et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care 2018;8(1):66

- Malbrain MLNG et al. It is time for improved fluid stewardship. ICU Manag Pract 2018;18(3):158–62

- Malbrain ML et al (eds). Rational Use of Intravenous Fluids in Critically Ill Patients. Springer, Cham

- Malbrain MLNG et al. Intravenous fluid therapy in the perioperative and critical care setting: Executive summary of the International Fluid Academy (IFA). Ann Intensive Care 2020;10(1):64.