A type of immune cell that contributes to inflammatory bowel disease exists in two forms, ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and a new study from the Francis Crick Institute in London has characterised these distinct populations, which could help scientists to develop treatments targeting inflammation while preserving healthy gut function.

These two populations are akin to worker and soldier ants, playing different roles depending on their context.

The ‘worker ant’ population of immune cells is found naturally in the gut and helps keep the lining of the intestines healthy. The other population is triggered in response to infection by a pathogen. Similar to soldier ants, these immune cells are called in to help fight infection, travelling from lymph nodes – where they are produced – to the gut and other parts of the body to attack the invading pathogens. Although they are necessary to fight infection, these cells can cause excessive inflammation.

By studying the differences between these two cell populations in mice, a multidisciplinary research team has revealed potential ways to target the cells associated with immune-inflammatory diseases, while sparing the ones that help keep the gut healthy.

“Our findings may help ensure that future therapies for inflammatory diseases that target these cells do not inadvertently damage the resident intestinal population important for gut health,” says Gitta Stockinger, Francis Crick Institute group leader and senior author of the paper.

The results might also explain why attempts to target molecules released by these cells have been successful in inflammatory conditions affecting the skin (such as psoriasis) and nervous system (such as multiple sclerosis) but have failed in gut-specific conditions like Crohn’s disease.

T helper 17 (Th17) cells have a known role in inflammatory disorders, but also help to keep the gut lining healthy. Previous studies attempting to distinguish between these two functions have studied Th17 cells in isolation in culture dishes, failing to mimic the complex biology of the immune system and microbiome inside the body.

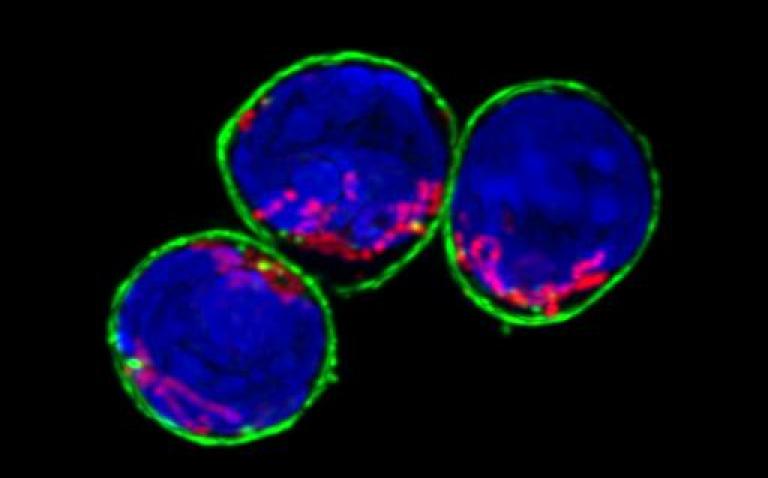

In this study, researchers at the Crick and King’s College London investigated Th17 cells in mice activated by either harmless microbes normally present in the gut (gut flora), or an intestinal pathogen equivalent to a type of E.coli in humans. They used genetically modified mice in which activated Th17 cells are fluorescently labelled, marking them for further analysis.

The gut flora-activated Th17 cells kept their function as a protective barrier and did not cause inflammation. By contrast, the pathogen-activated Th17 cells vigorously released pro-inflammatory signals and caused widespread inflammation.

To show that the two populations are distinct in the gut, the team infected gut-flora activated Th17 mice with the pathogen and used a drug to block any new Th17 cells from moving to the gut. The Th17 cells analysed were non-inflammatory, confirming that the resident Th17 are distinct from pathogen-activated Th17 cells and have a different role in the body. However, blocking the invasion of the fighter Th17 cells into the gut prevented the mice from successfully fighting off the infection.

“Th17 cells clearly have many roles in the body – and we need them to fight off infection and keep our intestines healthy,” says Gitta. “Any treatment for inflammatory disease would need to dampen the abnormal attack of Th17 cells on healthy tissues, without causing digestive complications or an inability to fight off germs.”

Computer analysis by Saeed Shoaie’s group at King’s College London, combined with cell biology analysis by Max Gutierrez’s group at the Crick, revealed that the two cell populations metabolised nutrients differently too. The flora-activated Th17 cells had minimal metabolic activity, similar to that of immune cells that stay dormant until they need to respond. In contrast, the pathogen-activated Th17 cells were very metabolically active, displaying a metabolic profile typical of cells that cause inflammation.

“The differences that we detected in the metabolism of these two cell populations give us a new opportunity to selectively target the pathogenic cells, while leaving the gut-resident ones intact,” says Sara Omenetti, Crick postdoc and first author of the paper. “This could form the basis of more successful treatments for Crohn’s and other conditions, where targeting Th17 cells in the gut can actually worsen symptoms.”