Non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is going to be the next big challenge for the health economy.

A recent guidance by Public Health England1 reported the high obesity rate among England’s population: two thirds of adults, a quarter of 2-10-year-olds and one third of 11-15-year-olds are obese. The number of people who continue to have unhealthy and potentially dangerous weight is projected to rise and is of considerable public health concern.

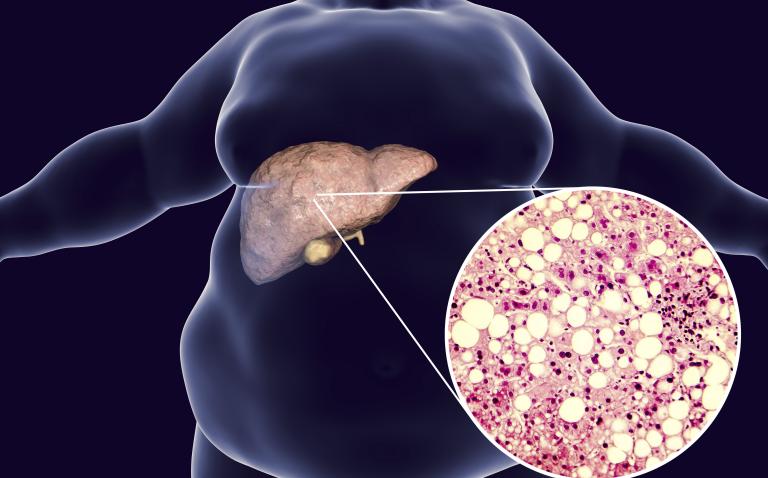

Liver mortality is the only cause of mortality that is rising in the UK.2 In the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines for the management of NAFLD 2016,3 NAFLD is defined as being characterised by excessive hepatic fat accumulation, associated with insulin resistance (IR), and defined by the presence of steatosis in >5% of hepatocytes. The risk factors are obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, sedentary lifestyle, PCOS, HBV, HCV.

NAFLD embraces two disease states:

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver (NAFL) which is a broad, mostly benign liver disease

- Non-Alcoholic Steato-Hepatitis (NASH) an inflammatory and progressive condition.

Liver disease presents itself on a wide spectrum from mild and self-limiting to sever with high mortality and affects eventually all organs. However the liver has a remarkable ability to regenerate but when severely compromised the ability to repair seems to disappear. As the liver regulates the concentration of constituents in the blood it affects the function of all organs in the body maintaining homeostasis (it processes food, combats infections, detoxifies, manufacturing bile, hormones, clotting factors, proteins etc and iIt stores iron, vitamins as well as producing and storing energy).

Interestingly NAFLD is particularly prevalent in the Middle East (32%) and South America (30%), with Asia (27%), North America (24%) and Europe 24% slightly behind, with prevalence increasing with age (70-79-year-olds; 34%).4

NASH was the fastest increasing reason for liver transplantation between 2002 and 2011.

NADLF activity scores is determined by the extent of steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning degeneration and lobular inflammation. 25% of patients with NAFL will progress to NASH within three years and 44% within six years of which up to 38% will progress to cirrhosis and are at risk of decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Fibrosis scores above 3 indicate cirrhosis and resolution of the damage to the liver is currently considered unlikely and survival rate reduces drastically whereas scores below 2 do not seem to have an impact on survival.5

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) currently advises assessment for NAFLD in higher risk-groups only whereas EASL proposes to assess every patient’s lifestyle and all patients with metabolic syndrome. Current scoring seems to underestimate NAFL in a large number of patients and a number of scoring tools are in development.

Again NICE advises to treat ≥F3 only whereas EASL suggest to treat ≥F2 and patients at high risk of progression. In view of the importance of fibrosis reversal and the need to avoid progression of the disease, I would question the cost effectiveness in the longterm of the NICE recommendations.

Current treatment options are lifestyle changes, with the loss of 7-10% of weight the most effective way to affect steatosis, reducing it by up to 75%.6 Medical intervention, bariatric surgery and liver transplant are currently available with limited success. It has to be stressed that a multidisciplinary approach using the model from Oxford7 is a successful way forward, combining diabetology, hepatology and dietetic in a multidisciplinary metabolic hepatology clinic.

Current medical intervention included vitamin E, pioglitazone, obeticholic acid, liraglutide, elafibranor and many investigational compounds. The trials currently are not comparable as they look at different endpoints.8 It has not been decided if fibrosis improvement, NASH resolution or another new endpoint should be the used as standard in the future. From the recent trial, there also seem to be signals that the liver can recover from cirrhosis to a certain degree when NAFLD is adequately treated.

It has become clear a single drug treats all strategy may not be effective to treat a multifactorial disease such as NAFLD. Drug combinations with complementary mechanisms of action will likely be the best approach and a triple therapy will be the norm targeting each of the following areas:

1. A drug targeting the fat deposition and the metabolic syndrome

- De Novo Lipognese, fat deposition and metabolic syndrome directly (aramchol) or via the PPAR α β δ (pioglitazone, elafibranor) and FXRE receptors (obeticholic acid)

2. An anti-inflammatory drug targeting

- Oxidative stress (Vitamin E), inflammation (Cenicriviroc) and apotosis (Emricasan)

3. An anti-fibrotic drug targeting

- Fibrosis (selonsertib).

None of the currently available or proposed medication will probably still be in use in the next few years and at EASL 2018 and 2019, many new molecules and combinations were presented with potential to be effective in the treatment of NAFLD. Several companies have an active pipeline in NAFLD and the global market is estimated to reach $1.6 billion in 2020.9

This is an area of extremely fast development of new treatments and careful attention and pharmaceutical expertise will be required to develop the treatment strategies to deal with the explosive growth of patients diagnosed with NAFL and NASH.

References

- Public Health England Guidance: Childhood obesity: applying all our Health. April 2015.

- Williams R et al. Addressing liver disease in the UK: a blueprint for attaining excellence in health care and reducing premature mortality from lifestyle issues of excess consumption of alcohol, obesity, and viral hepatitis. Lancet 2014:29;384(9958):1953-9.

- EASL-EASD-EASO. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;64(6):1388-402.

- Younussi et al. AASL The globalization of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Prevalence and impact on world health. Hepatology 2016;64:73-84.

- Eckstedt M et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow up. Hepatology 2015;61(5):1547-54.

- Lazo M et al. Effect of a 12-month intensive lifestyle intervention on hepatic steatosis in adults With type 2 diabetes. Diab Care 2010;33:2156-63.

- Cobbold J Piloting a multidisciplinary clinic for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: initial 5-year experience. BMJ Frontline Gastroenterol 2013;4(4):263-9.

- Dunn W. Therapies for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Res 2017;1:214-220

- Allied Market Research. www.alliedmarketresearch.com/nonalcoholic-steatohepatitis-NASH-market (accessed April 2019).