The creation of a Fluid Stewardship Committee at Royal Blackburn Hospital has led to better systems, processes and innovations to support effective intravenous fluid prescribing and management.

I first heard the term ‘fluid stewardship’ in a corridor conversation with our Acute Care Team lead nurse, Jane Dean, in 2019; who, in turn, had only recently come across it in a tweet from the International Fluid Academy.1 The term struck a chord; it sounded like ‘antimicrobial stewardship’, so surely must be about everything to do with the safe and effective management of fluids in hospitals?

The term appears to have been coined in the mid-2010s, with most definitions focusing on the clinical aspects of fluid management. For example, ‘the primary goal of fluid stewardship is to optimise clinical outcomes while minimising unintended consequences of intravenous fluid administration’.2

However, the outcome of the corridor conversation resulted in a more holistic description for my Trust – we wanted to cover all aspects of fluid management and developed a list (Figure 1) that we circulated to some like-minded, ‘fluid-thinking’ colleagues.

Within a fortnight, the Trust’s Fluid Stewardship Committee was formed, with multidisciplinary membership from the consultant body, nursing, pharmacy, and Quality & Safety. Our aim was to examine and optimise all the areas on our list.

The remainder of this article describes our journey so far; a follow-up article will describe how the developments mentioned have progressed.

The Fluid Stewardship Committee

The committee initially met fortnightly while we assessed what was required, and who should take responsibility for what. The professional leads took responsibility for the educational elements for their respective professions, although there was much overlap.

The pharmacy elements were led by me with support from two colleagues. Our Quality & Safety lead kept us all in check; sticking to the agenda and helping figure out how we could measure outcomes.

NICE Clinical Guideline 174

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published Intravenous fluid therapy in adults in hospital3 in 2013, and which was the standard used to develop our educational programme and support materials. It describes how to assess and prescribe fluids for the most common indications (with caveated exclusions for patient groups with more specialised fluid prescribing needs).

It introduces the concept of ‘The 5 Rs’: Resuscitation fluid; Routine maintenance fluid; Replacement fluid; and Redistribution fluid; showing algorithms for each element covering assessment and prescribing, with the fifth ‘R’ Reassessment underpinning them all.

On one level, this is all one needs to know to manage those scenarios; however, there are many myths perpetuated from the time before the guidance, with many having been developed through the perceived wisdom of practice rather than being taught.

There is a paucity of education in Schools of Medicine, Pharmacy and Nursing surrounding the teaching of fluid prescribing, with mnemonics such as ‘one bag of salt to two bags of sugar’… or is it ‘two bags of salt to one of sugar?’ persisting with some of the more experienced clinicians.

And this custom gets passed down the years, resulting in large volumes of sodium chloride 0.9% being inappropriately prescribed and administered, giving patients (irrespective of their body weight and fluid requirements) 154mmol of sodium and chloride with every litre infused: which is more than twice the daily requirements for a 70kg individual.

Harm can and does occur. The National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths reported that up to one in five patients who had received IV fluids suffered from complications or morbidities due to inappropriate prescribing or administration.4

Our first task was therefore to try to break this cycle of ‘fluid learning’.

Staff engagement and education

Key to improving fluid stewardship was disseminating the right knowledge to the doctors, pharmacists, and nurses. To achieve consistency of message, and to ensure all important elements of fluid management were covered, we decided to produce a suite of short films describing:

- the concept of fluid stewardship

- fluid resuscitation

- routine maintenance fluid

- fluid replacement and fluid redistribution.

The films were made with the assistance of Dr Justin Roberts (ICU Consultant with a fluid interest), who is also a key member in the Fluid Stewardship Committee and has helped drive the prescribing effectiveness side of the programme.

A fifth film examining fluid balance in more detail is now included in the suite.

Our films were uploaded to a new fluid stewardship page of the intranet, with additional summary points under each embedded film to act as aide memoirs once each film had been viewed. The films have also been posted on the Trust’s internet, so a wider audience can view them and perhaps use them as educational tools, or inform their own fluid stewardship programmes.

Nurse practice educators were charged with informing the nursing staff; the critical care directorate consultant training lead took responsibility for doctors, and I arranged a series of education events for pharmacists and pre-registration pharmacists, with our induction programme for new pharmacists including a fluid stewardship element. Since July 2021, I have also delivered a fluid stewardship training session to the new FY1 intake as part of their core induction.

We are fortunate in that the Trust has made significant investment in the pharmacy team through our Dedicated Ward Pharmacy service. This means most wards have a dedicated pharmacist, with enhanced pharmacy technician resource, so pharmacists can routinely participate in the daily consultant-led, multi-disciplinary ward rounds where they can actively influence all aspects of prescribing (including fluids), as well as being proactive in discharge planning (which was historically an oxymoronic term).6,7

Pharmacists, empowered with the knowledge of our fluid stewardship programme, have become, in effect, ‘practice educators’ and ‘fluid stewards’ for the pharmaceutical aspects of fluid management on each ward.

Introduction of a new maintenance fluid

The recommendation of CG174 for routine maintenance fluid is to use a ‘balanced fluid’ that delivers the basic daily water and electrolyte requirements for an adult. That is:

- 25ml/kg/day of water – in practice rounded to the nearest 100ml, and only 20ml/kg/day for patients who are: frail; have renal impairment or cardiac failure; or who are malnourished

- 1mmol/kg/day of potassium, sodium, and chloride

- 50–110g glucose/day to limit starvation ketosis (NB that this amount of glucose does not meet a person’s nutritional needs).

Historically we had used sodium chloride 0.18% in glucose 4% with potassium chloride (0.15% or 0.3%), which is complicated to prescribe, and get right on a paper prescription chart (the Trust does not yet have electronic prescribing).

Our fluid supplier (Baxter) recently introduced a product called Maintelyte,8 that closely matches CG174’s recommendation for maintenance fluid content. The shorter, memorable, and more meaningful name was an attractive way to make prescribing for this indication easier, safer, and effective, so we sought and gained approval to use it in the Trust from the Medicines Management Board.

It was launched at the beginning of December 2020 with communications through the various professions’ channels within the Trust, and posters in treatment rooms, and was referred to in our engagement film on routine maintenance fluid.

Reassessment is an important aspect of routine maintenance fluid monitoring, and we recommend checking electrolyte serum concentrations two to three times a week. Maintelyte® contains 20mmol KCl in each litre bag, which equates to around 0.5mmol/kg/day potassium if dosed correctly, so occasional supplementation of additional potassium with our original maintenance fluid is required.

Fluid stock lists

Historically nurses could request fluids from pharmacy stores on an order sheet that contained around 30 different fluids that were often ordered by ward housekeepers several times each week; this was quite inefficient for picking and deliveries.

We changed stock orders of fluids, so that they are now generated weekly by pharmacy assistants, which are topped-up when the regular stock medicines are ordered for each ward. This has resulted in time efficiencies because each ward now typically only receives one fluid order/week, which in most cases can be accommodated on the ward because fluids used infrequently have been removed.

If a patient has a genuine need for a less frequently supplied fluid, this must now be screened by a ward pharmacist to sense-check it is appropriate, and, if necessary, an individual supply will be ordered.

With the introduction of Maintelyte, members of the pharmacy team took the opportunity to review, with each ward manager, what their wards empirically needed. This included removing some fluids that did not appear to have an indication and adding Maintelyte on to each stock list. Initially the amount stocked of each fluid was a best guess, and we have monitored each ward’s usage with subsequent tailoring of quantities.

Figure 2 shows the effect on the two fluids that Maintelyte ostensibly replaces; however, its use across the Trust far exceeds what was replaced, possibly suggesting the ease of prescribing has led to increased usage. However, the baseline prescribing audit shows things in a different light.

First prescribing audit

With all these changes we wanted to get an idea of how well fluids were being prescribed, prior to further developments being introduced. We were fortunate to have a fourth-year medical student with an interest in fluid stewardship, and in need of an audit, so an audit was designed and tested on two medical wards in February 2021.

The primary aim was to collect and analyse Trust-wide baseline data on fluid prescribing in relation to the standards in NICE CG174. It was also hoped to identify any barriers to appropriate fluid prescribing and evaluate the impact of education on fluid prescribing standards.

Figure 3 shows the audit’s findings of whether the indication for a fluid prescription was recorded in the notes. In half the prescription charts examined no clear indication was documented; what was not examined, and might feature in a future audit, is whether the indications that were captured were accurate and appropriate for the clinical situation of the patients.

Our current prescription chart does not provide space to capture an indication for a fluid, although it does for other regular or when-required medicines. The audit provided evidence of patients’ weights being recorded (70% were recorded; 30% were not) which has a significant bearing on a pharmacist’s ability to clinically check the appropriateness of the volume of fluid prescribed for routine maintenance, redistribution, and resuscitation.

The audit examined the frequency of types of fluid prescribed (Figure 4) and correlated this with the indication. As well as reinforcing the lack of indication in half of the prescriptions we found that fluids were being prescribed for an inappropriate indication; for example, Plasma-Lyte 148 was used as routine maintenance in one patient; sodium chloride 0.9% had been erroneously used, where the indications were recorded, when our guidance was to use Plasma-Lyte 148 prescribed for redistribution and resuscitation and Maintelyte for routine maintenance; and Maintelyte had been used for redistribution when its sole indication is routine maintenance.

The volumes prescribed were recorded, with 93% (n=28) being 1000ml and 7% (n=2) being 250ml. A tailored volume should be prescribed for replacement, redistribution, and routine maintenance such that, when rounded to the nearest 100ml, volumes other than 1000ml prescribed in many cases would be expected.

Junior doctors were asked to complete a questionnaire in the same period the audit took place to capture their perceptions and understanding of fluid stewardship.

The results are shown in Table 1 and perhaps explain the audit findings, with junior doctors confident in their prescribing of fluids, although the audit shows this is starkly misplaced; feeling they receive good training as an undergraduate, while slightly less so on the job; and that they would benefit from further training… although none of them had watched the films on the intranet.

Clearly there is much work to do regarding the education and engagement of junior doctors. The fluid stewardship induction session for new foundation year doctors will help, but we have two other developments in the pipeline for 2021 that should make it easier for prescribers to perform a safe and effective job when prescribing fluids.

New fluid prescription chart

The Trust is about to introduce a new paper prescription chart (a 12-page booklet) ahead of electronic prescribing in late 2022. The fluid section has been extensively revised to support our fluid stewardship programme, and now appears as a gatefold section with printed reminders of how to prescribe fluids for different indications (Figure 5), with a separate section for resuscitation fluid, and checkboxes to show the other fluid indication(s) (Figure 6).

Blippit Meds app

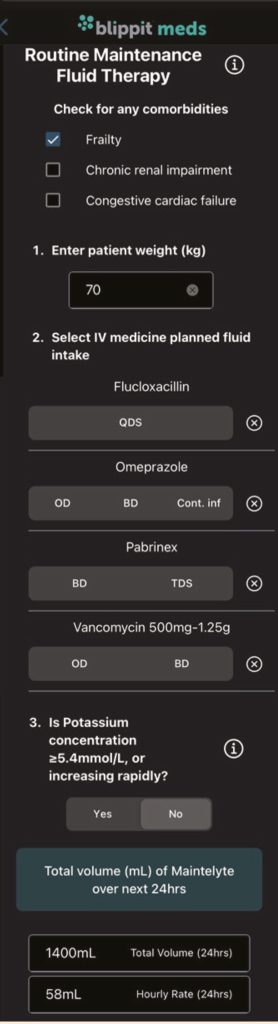

The concept of using a smartphone application to help prescribers choose the right fluid and the right dose volume came out of conversations with the Fluid Stewardship Committee. Anyone watching our educational films, viewing the key points on the intranet, and supported by the new prescription chart should have the empirical knowledge to prescribe fluids effectively; however, we really wanted to make it easy to do an effective job.

The critical care team had been using an app that we had devised a few months earlier – Blippit Meds. This was originally designed to help nurses quickly view injectable drugs’ monographs in the treatment rooms without having to rely on paper copies or computers; they could access them on their smartphones.

We approached our app developer to see if a fluid decision aid could be made that followed the principles of the NICE CG174 prescribing algorithm, and with some simple choices and inputs, for example, a patient’s weight, could show the right fluid choice and volume for a given clinical situation. It turns out this was possible, and at the time of writing the final development phase is taking place and will launch as soon as it is registered as a medical device.

A training film has been developed, showing clinicians how to use the Blippit Meds fluid prescribing decision aid as well as the injectable monographs section. This can be seen at https://bit.ly/BlippitMeds.

As an example, the composite screenshot in Figure 7 illustrates the routine maintenance calculator; one of three calculators in the app. Key ‘smart’ features have been included to ensure that variables such as comorbidities, ongoing intravenous antibiotic volumes are included when working out dosing, and finally it shows the dose and choice of fluid based on the user’s total inputs.

For all three calculators, if additional fluids selected means the calculated volume is in the range 0–200ml, then a pop-up message appears suggesting no extra fluid is required today and to reassess the next day. If the volume of additional fluids exceeds the calculated volume, then a separate pop-up message appears warning the clinician there is a risk of fluid overload and they should consult a senior decision-maker.

What next?

Our imperative is to successfully launch the new prescription chart and the Blippit Meds app, with appropriate communications to the Trust’s clinicians. The pharmacists delivering our Dedicated Ward Pharmacy service will be well placed to support prescribers and nurses to utilise these two new innovations.

Ward fluid stocklists will also be reviewed again to ensure the range of fluids and volumes match changes in demand. And then, we will re-audit the fluid prescriptions to see if all the changes have improved the quality of prescribing, and take whatever action is necessary to address any concerns raised, or hopefully have a warm sense of achievement of a job well done!

Conclusions

To find out what happened next, look out for Part 2 of this series (coming soon), and, in the meantime, perhaps consider how you could introduce a fluid stewardship programme in your organisation and become good ‘fluid stewards’.

References

- International Fluid Academy 2021. www.fluidacademy.org (accessed Sept 2021).

- Malbrain M et al. It is time for improved fluid stewardship. ICU Manage Pract 2018;18(3). https://healthmanagement.org/c/icu/issuearticle/it-is-time-for-improved-fluid-stewardship (accessed Sept 2021).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intravenous fluid therapy in adults in hospital. CG174. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg174 (accessed Sept 2021).

- National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths. The 2000 Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths. www.ncepod.org.uk/2000report3/TaNfull.pdf (accessed Sept 2021).

- East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust (2021). Fluid Stewardship. https://elht.nhs.uk/services/pharmacy/fluid-stewardship (accessed Sept 2021).

- Gray A, Wallett J, Fletcher N. Dedicated ward pharmacists make an impact. Hospital Pharmacy Europe. https://hospitalpharmacyeurope.com/news/editors-pick/dedicated-ward-pharmacists-make-an-impact/ (accessed Sept 2021).

- East Lancashire Hospitals’ Pharmacy Directorate. ELHT Dedicated Ward Pharmacy: Haelo Graduation Film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLaMzyujh60 (accessed Sept 2021).

- Summary of Product Characteristics. Maintelyte solution for infusion. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/ 10010 (accessed Sept 2021).

First published on our sister publication Hospital Pharmacy Europe.