A study by investigators at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) has discovered a molecule in the lymphatic system that has the potential to play a role in autoimmune disease.

The study was published online in Science Immunology.

Lead investigator Theresa Lu, MD, PhD, senior scientist in the Autoimmunity and Inflammation Program at the HSS Research Institute, and colleagues launched the study to gain a better understanding of how the immune system works.

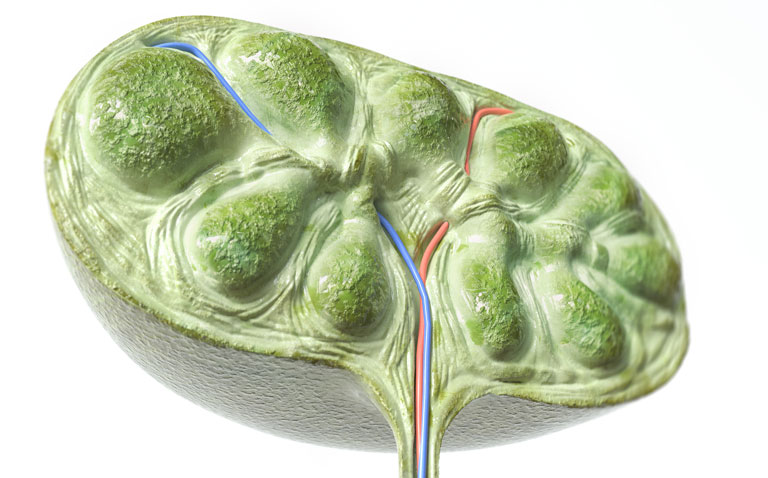

Dr. Lu’s study focused on the lymphoid tissues, which house immune cells and are sites of immune cell activation. Lymphoid tissues, which include the tonsils, spleen and lymph nodes, contain structural elements, such as fibroblasts and blood vessels. These structural elements were thought to mainly provide an infrastructure for the immune cells, but recent advances in the field have shown that they actively shape immune cell responses, and multiple populations of fibroblasts have different functions, according to Dr. Lu.

“We found that one fibroblast population expressed a molecule called CCL2 in the area of antibody-secreting immune cells, called plasma cells. We focused on the CCL2-expressing fibroblasts to see if they regulate plasma cell function,” she explained. “We found that CCL2 limits the magnitude of plasma cell responses by acting on an intermediary cell to reduce plasma cell survival. This was surprising in some ways, as CCL2 can also promote inflammation, and yet we are finding a role in limiting immune responses. This underscores the multiple functions that any molecule can have in different contexts.“

The findings have implications for better understanding autoimmune diseases, according to Dr Lu. Plasma cells in autoimmune diseases generate autoantibodies that then deposit and cause inflammation in organs such as the kidneys and skin. “By understanding that plasma cells can be controlled by this subset of fibroblasts, we can study these fibroblasts to see if they are perhaps not working properly in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. We can then search for a way correct the malfunction, so they are less likely to cause disease,” she notes.

“As the immune system is so central to how well our bodies function and often acts in similar ways in a number of different settings, what we are learning about manipulating fibroblasts can also help the biomedical community better understand how to treat related processes, such as healing after a musculoskeletal injury, fighting cancer and fighting infections,” she adds. “For example, medications used in adults and children with different forms of autoimmune inflammatory arthritis or lupus are being examined in the setting of coronavirus infections. We all learn from each other.”